Editor’s note: This guest post first appeared on the Meyer Memorial Trust’s blog.

Meyer recently issued a statement on equity, a primer on our mission as a foundation and as individuals to do what is needed to enrich Oregon.

The statement is 429 words. It represents our recognition that to move forward, we have to look back and own the biases, oppression and disparities that shape this place that is our home. But it also represents a journey that the foundation started in earnest when we revised Meyer’s mission, vision and values.

I’m Oregon through and through, Portland-born and Stanford-educated. My socially liberal bona fides were well-honed. My friends, colleagues and acquaintances came in assorted colors and ethnicities, and from all economic backgrounds. I’d seen disparities up close and first hand during my tenure at Friends of the Children. I believed in equality. I believed we could do better. But the Doug Stamm of five years ago wasn’t meaningfully involved in the struggle. My hands weren’t reaching for the wheel to help drive the conversation about equity. So when we wrote Meyer’s values, these words meant something broad and unspecified to me: Flourishing and equitable communities are places with healthy environments where all current and future residents have fair access to opportunities to learn, work, prosper and participate in a vibrant cultural and civic life.

I cared. But I couldn’t fathom my role in removing the barriers that prohibit many Oregonians from having fair access to opportunities.

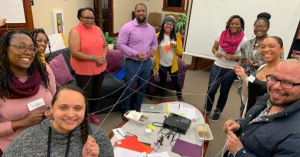

That was 2009. In 2013, the reality hit home in a real way when Meyer’s staff had a retreat to talk about race, white privilege, disparity and equity. I want to thank my colleagues, particularly my colleagues of color, for their honesty and fearlessness. The experiences they shared brought oppression home for me. The costs of personal and systemic prejudice were laid bare. At the end of two painful days of conversations, I knew I wanted off the sidelines. Their stories provoked me intellectually to think about what we meant when we talked about “a flourishing and equitable Oregon.” And they emboldened me to push myself and this venerable organization. I wanted to do more than nod my head along when people decried what was wrong, when the topic turned to urban blight, rural poverty, hunger, homelessness and hate. I wanted to be an ally in moving the needle toward real equity.

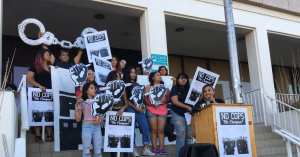

To truly be an equitable place, with the changing demographics in our state, Meyer had to address issues of developing fair access. We needed to be intentional. And that meant facing up to structural and institutional racism.

It is mere lip service if diversity doesn’t carry throughout an organization. Right off the bat, we knew that Meyer didn’t have the people of color at the management level that we needed to make this a richer foundation. We’d made progress in diversifying our staff but where we fell short was in diversifying our executive team. For several years, we had talked about wanting to see a change in that direction. People tried in earnest and we kept ending up with great candidates who were white. We refined our recruitment process, we promoted from within, but still our hiring didn’t change. A white friend who runs a Northwest foundation told me about a candidate he talked with for an hour. At the end of the interview, he really liked the guy. They just clicked. Then he realized it was because the candidate was exactly like him: white, male, Ivy League-educated. No wonder it was so easy to feel connected to the candidate – and to assume that affinity meant the man was the most qualified. That story really struck me. It was easy to fall into the mindset that we’d done all we could at Meyer; this was Portland, the whitest major city in America, after all. Of course we hired people just like ourselves.

We needed to push beyond those sensibilities to fill positions. We wanted qualified candidates: Degrees from Harvard and Stanford and a familiar, middle class upbringing are fine, but we began looking for people who were more broadly accomplished and could do the work. I reached out to executive directors of color among my friends and cohorts, and I told them I was hellbound to have qualified people of color in my finalist pools. Then I partnered with a firm with a history of recruiting folks of color at the executive level. With their help, Meyer’s recent hires have been top-notch.

Equity work is not a numbers game. But we are making real progress at Meyer, on the board of trustees, in staff and in management positions.

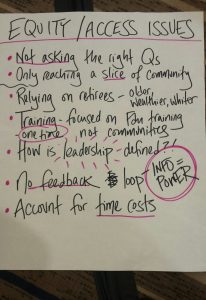

Together, we’ve gone through intensive trainings on race, racial equity and institutional, structural and individual racism. And we’ve worked hard to define our shared definition of equity as the existence of conditions where all people can reach their full potential. It has helped us come to the table as partners. It has shaped how we do what we do, giving us a lens through which to consider programs and determine where our funding can do the most good for communities that need the most. It has shaped how we measure our outcomes. It has focused our mission in philanthropy, a field that exists at the nexus of power and poverty, wealth and want.

But there’s still more to do. The journey, albeit indefinite, requires some road marks to ensure that Meyer continues in the right direction. One way we aim to stay on target is to cooperatively engage with communities and grantees to maintain an ongoing dialogue about where we are and where we ought to be.

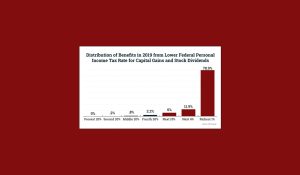

For Meyer, it has been an evolution. For me, it’s been a transformation. Earlier this year, I became a grandfather. If you really care about the quality of life for your kids and your grandkids, you’ve got to see the upside to working to eliminate bias and oppression. Today, I see my role, and Meyer’s, as being actively engaged in the struggle. Let’s be clear: biases and disparities drive the societal costs philanthropy tries so hard to mitigate. Three years after the Occupy Wall Street Movement, I’m not so concerned about the top one-percent. But I am deeply concerned about the 17 percent of Oregonians in poverty. Can we do more to move that lower 17% up? I think so. The opportunity to succeed must not be tilted in favor of those who are white or born of privilege or come from a power base. Anyone can feather their own nest. Having a stake in equity means asking yourself: What can I do beyond that? Am I working to tear down structural and institutional barriers for people of color, for people in poverty, so they can build their own nests?

That’s the business I want to be in. And it’s work Meyer has taken on. The reason is simple: we have a shared destiny.

Doug A. Stamm is CEO of Meyer Memorial Trust in Portland, Oregon.