Editor’s Note: This reflection on our most recent data report was originally published as a Letter to the Editor in The Chronicle of Philanthropy.

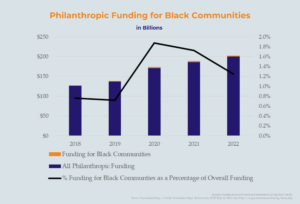

The controversy surrounding NCRP’s latest report, Black Funding Denied, has been intense. Many of the 25 community foundations in our sample set have said that the data detailing grantmaking explicitly designated to Black communities does not adequately capture their overall racial equity efforts. Some have even gone so far as calling for NCRP to retract the report. Yet, movement groups, including Black-led NCRP nonprofit members, tell us that the research reflects their lived experience.

As our country engages in the deepest national reckoning with anti-Black racism and violence since the Civil Rights Movement, we felt it was a moral imperative to shine a light on this disconnect.

NCRP was founded to bring the voices of nonprofits – especially those by and for marginalized communities – into the philanthropic sector. Most nonprofits are reluctant to be publicly critical of foundations because of the power difference inherent in their status as potential future (or current) grantees. Funders too often hesitate to criticize their peers, in part due to a pervasive “politeness” culture that can inhibit and insulate the sector from productive discomfort necessary for growth.

As one of the few philanthropy-serving organizations with both foundation supporters and nonprofit members, NCRP serves as a bridge between these two sets of changemakers. Our value to the sector lies in our willingness to play the role of critical friend, provoking difficult conversations like this one. We have an obligation to our philanthropic colleagues to be collaborative, but also an obligation to hold a mirror up that reflects the reality of our movement partners. It is a tough balancing act.

NCRP has three core organizational values: Power, humility and accountability. We strive to empower nonprofits in their relationships with funders and push philanthropy to be more responsive to the needs of those with the least power, wealth and opportunity in our society. We are humble enough to know we don’t do that perfectly nor do we have all the answers. But we also know that there can be no accountability if we aren’t willing to call the question.

We have learned a lot from this controversy and want to share our reflections. The nuanced and sometimes painful discussions catalyzed by this research have crystalized two consensus points among critics and proponents alike, notably that:

- Community foundations can and must do more to support Black lives and liberation.

- Funders have a shared responsibility for and self-interest in the creation of a better system for transparent, accurate and timely sector-wide data.

We believe these areas of agreement represent fertile ground for ways we can move forward together.

What would we do differently?

No one denies the report’s central conclusion: That community foundations can and must do more to promote the thriving and liberation of Black people. However, initial confusion around what was and was not being measured (and why) contributed unnecessarily to muddying the waters. That could have been avoided by greater precision in language used in the body of the report and the press release (both of which have since been edited for clarity) that the analysis was specifically and intentionally around grantmaking explicitly designated for Black communities. We also should have included an in-depth explanation of why we chose that standard as a measure for accountability in the first place.

Secondly, we could have been more proactive in our outreach to community foundations in our data set. We did contact each funder via email to inform them that they were being included in this research brief and offer a conversation prior to release. However, we could have engaged further with staff and leadership working to rally support internally and externally to do more to support Black communities.

Lastly, we defined the geographic service area for some of the foundations differently than they define their service area. At a minimum, we could have noted this distinction in our analysis.

Common ground: Making a commitment to better funding and better data

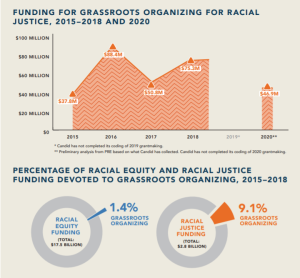

We know several community foundations are taking bold steps in 2020 to benefit Black communities and NCRP will continue to highlight and share announcements of those efforts as they become public. Foundations concerned about their reputations have the power to show the field exactly what they’ve accomplished and how frontline groups addressing structural racial injustice can access those resources. Foundations looking to improve their racial equity giving have a plethora of resources and organizations at the ready to support them (including ABFE, PRE and Equity in the Center among others).

But there will be no way to measure progress or hold ourselves accountable without a serious, sustained effort to make philanthropic sector data intersectional, transparent and accessible.

Candid expects to have complete data for 2019 available early next year. NCRP and other groups will likely publish reports in 2021 using that data to analyze important issues in philanthropy. As a first step we encourage community foundations who feel their data was miscoded to work with Candid to make corrections. And we encourage all foundations to take the time now to make sure their 2019 grantmaking data is as accurate as possible so that we all have an updated picture of the state of the sector.

NCRP has been part of discussions for years with Candid and other groups that comprise the infrastructure that supports philanthropy about how to improve sector data. There’s no doubt the data isn’t perfect (see this helpful post from Candid’s Executive Vice President Jacob Harold for details) and there are important steps that Candid should take to make it better. But funders need to take responsibility for the fact that ultimately they are the ones that determine what universe of data Candid – and all of us – have to work with in the first place. They should be working with Candid to create systems that enable faster data submission to avoid multi-year time lags, taxonomies that reflect the intersectional nature of grantmaking and greater data access for communities and others seeking to understand the sector better.

Foundations have an obligation to be transparent with communities they serve by making their data publicly accessible, either through working with Candid or on their own websites. The existence of external and internal obstacles to making this transparency a reality do not absolve foundations from being held accountable by us or anyone else.

The urgency of the issue, not just the moment, demands purposeful, explicit funding and transparent accountability. We encourage funders to approach this conversation with honest vulnerability and to use it as an opportunity to strengthen and build community relationships and trust.

Aaron Dorfman is president and CEO of NCRP. Rev. Dr. Starsky Wilson is the chair of NCRP board of directors, the outgoing president of Deaconess Foundation, and the incoming president of the Children’s Defense Fund.

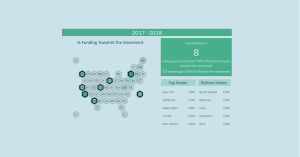

This report is part of NCRP’s Movement Investment Project, which is designed to help philanthropy get better at supporting movements. Funders of all types might find some of the resources there helpful. The first 18 months of the initiative focused on the pro-immigrant, pro-refugee movement.