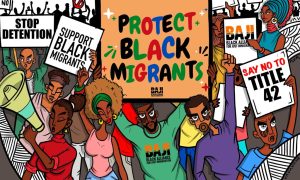

From street-level interactions between law enforcement and the undocumented to penal systems obscuring the incarcerated, the unique concerns Latinx communities face in the American criminal justice system are often overlooked in conversations about reform.

Last month, Public Welfare Foundation (PWF) hosted the discussion El Color de la Justicia: Raising Latinx Voices for Criminal Justice Reform. PWF works to advance justice and opportunity for people in need, focusing its grantmaking on criminal justice, youth justice and workers’ rights – often through multi-year and general operating support grants to bolster grantees’ staying power.

The event highlighted the challenges criminal justice reformers face when fighting alongside Latinx populations. Ryan King, senior fellow of the Urban Institute’s Justice Policy Center, Juan Cartagena, President & General Counsel of LatinoJustice PRLDEF and Sara Totonchi, executive director of the Southern Center for Human Rights discussed their work on these challenges.

Ryan discussed the paucity of data across nearly every state illustrating even the most basic information about incarcerated Latinos and Latinas. According to Justice Policy Center data, states usually fail to even delineate Latinx individuals from other races. For instance, Florida officially claims its prison population is 48 percent white, 48 percent black and 4 percent other.

Juan talked about simple desires for fairness in the application of law and the fostering of safe communities. Stereotypes still play an undue role in interactions between law enforcement and people of color. Latinx people are particularly victimized by associations with the drug trade in Central and South America – Juan made sure to call out Attorney General Jeff Sessions and the Trump administration writ large for their role in furthering this stigmatization.

The intersection of immigration and the criminal justice system, or “crimmigration” as Sara termed it, is fraught with perverse incentives. She dived into how the criminal justice system can often be used as a form of social control. In Atlanta, where her organization is located, it’s not uncommon to see ICE vehicles parked outside public schools – waiting to detain parents of undocumented students should they arrive to pick up their children. Agreements between local police and the federal government, formalized through 287G forms, authorize state and municipal law enforcement to join ICE in this campaign of immigrant intimidation and imprisonment.

The experts weren’t without solutions, though. Funders need to be agile, Sara said. Both rapid response funds and long-term investments are essential. Ryan cautioned funders not to fixate solely on change at the federal level, as there’s fruitful work to be done at the state and local levels too. Juan would like to see broader stakeholder engagement to ensure prosecutors, police, victims and others are seated at the table when working toward change.

The struggle for justice besetting the Latinx community existed long before last November’s election, and will not fade any time soon. It’s time we take this to heart. Our great privilege as white Americans lies in the energy we spare not fretting our place in America, and it’s paramount we invest this surplus into action. Guiding lights like the Justice Policy Center know where the battles are, and steady hands like the Southern Center for Human Rights and LatinoJustice PRLDEF know how to fight them. Let’s make sure they and their allies have the resources they need, like access to rapid response funds and multi-year, general support grants, while we stand with fortitude beside them.

Troy Price is NCRP’s membership and fundraising intern. Follow @NCRP on Twitter.

NCRP Members engaged in activism around Latinx immigrants’ rights and quality of life include: