I started noticing a change on my daily walks a couple months ago: a portrait of an Asian-American woman with the words “We belong here” written on them. These vibrant portraits, created by artist Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya, are especially poignant amidst an environment of increased violence against AAPI people.

The portrayal of women in the artwork also challenges stereotypes of AAPI women as timid and docile – stereotypes with sexist and misogynistic undertones. These stereotypes, in addition to deeply rooted and new forms of systematic racism and xenophobia lead to targeted gender-based anti-Asian violence. This has been especially evident over the past year and a half, with AAPI women reporting hate incidents 2.3 times more often than men.

credit: Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya. Source: “I Still Believe in Our City” campaign. Distributed via Creative Commons

It is also the combination of racism, sexism, and xenophobia that led to devastating murder of 8 AAPI people in Atlanta, Georgia in March, 6 of whom were women. It is a reminder that anti-Asian violence is a reproductive justice issue as it robs AAPI people of the freedom and safety to make the best choices for themselves, families, and communities.

Artwork like Phingbodhipakkiya’s is important not just for changing narratives about AAPI communities, but also for changing narratives around reproductive justice. The reproductive justice movement that was coined and founded by Black women also has a long history of active Asian American leaders. I recently spoke with one long-time activist, Eveline Shen, and Founding Executive Director of Forward Together (formerly known as Asian Communities for Reproductive Justice and Asian and Pacific Islanders for Reproductive Health) about how Asian Americans have a role in the reproductive justice movement, and how philanthropy can support the movement.

Asian Americans in the formation of reproductive justice

Shen, whose tenure with Forward Together began in 1999 and ended this past July, sees the natural connections between Asian American activism and the reproductive justice movement.

“Asian American activism throughout history has made the invisible, visible. For example, white supremacy and anti-Black racism pits Asian Americans against Black communities by creating this myth of a ‘model minority.’ And this myth then begins to obscure the ways poor people, working class Asian communities, Southeast Asian communities, and other marginalized communities within the Asian American community and what they face and deal with.”

Reproductive Justice leader

& Forward Together Founder

Eveline Shen

The same connections can be made with reproductive justice, as historic events such as the mass sterilizations of Puerto Rican, Mexican, Black and Indigenous women throughout history are not told as part of America’s history. More recent incidents, like the forced hysterectomies of immigrant women in refugee camps in Georgia, are still coming to light.

Social movements aim to reveal these struggles and trauma. As Shen describes: “This is about telling the history, taking off the veil and seeing, what did we experience coming here? Who is fighting against those in power that continue to harm our communities? And how do we bring that to the discourse?”

Reproductive justice is intersectional, but philanthropy remains largely siloed

In the late 1980s, a number of organizations led by Black, Indigenous, Asian and Latinx communities were created to address the reproductive oppression facing communities of color. In 1994, a dozen Black women, led by Loretta Ross, came together at a pro-choice conference and came up with the concept of reproductive justice to counter the largely white-led reproductive choice and reproductive health movements that did not examine issues of race or class. Loretta had the vision of bringing all of our groups together to build a multi-racial movement. In 2005, Forward Together, then known as Asian Communities for Reproductive Justice, published the ground-breaking paper, a New Vision for Reproductive Health, Rights and Justice which provided the framework for reproductive justice and helped to expand the ideological space for an intersectional analysis of reproductive justice and leadership within the movement.

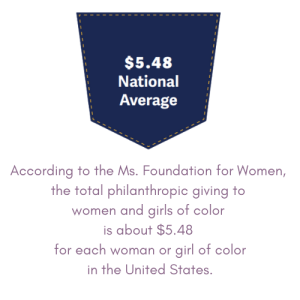

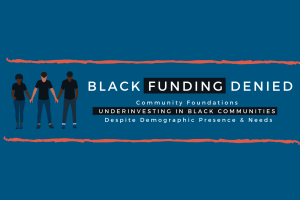

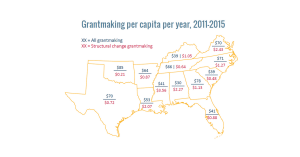

However, with a few exceptions, philanthropy has not supported BIPOC-led reproductive justice work in an intersectional way. In 2017, women and girls of color in the U.S. only received $5.48 per capita from philanthropy. Even less goes to organizations focused on reproductive justice work.

Reproductive Justice leaders understand that we don’t live siloed lives and that communities of color face multiple oppressions simultaneously. Using this intersectional analysis allows reproductive justice leaders to make visible the ways oppression impacts our communities and create effective solutions that address these complexities.

Shen draws inspiration from Asian American activists like Grace Lee Boggs and Yuri Kochiyama, both of whom focused on building power with a feminist lens and by working with Black-led and multi-racial movements. “They both walk the talk, focusing on community building, changing cultural norms, standing up to power and organizing within grassroots communities.”

“Reproductive justice gets pigeonholed,” says Shen. “This is seen as only a woman’s issue, or only about women of color. It’s been a fight to get [philanthropy] to fund us in a way that they fund some of the larger mainstream groups.”

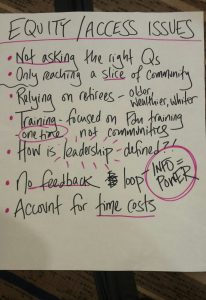

NCRP’s own research finds that the top 20 recipients of reproductive rights funding have gone to large national, predominantly white-led organizations. Often what happens is that philanthropy narrows in on a specific issue within the movement, such as legislation around abortion rights, and miss the intersectional nature of the movement.

“Abortion access is connected to economic justice, connected to immigrant rights, and ending gender-based violence…,” continues Shen. “The problems that then come because of systematic oppression are not siloed.”

Shen has seen some funding practices improve, particularly in leadership development for women of color, and more funding for trans and non-binary people within the movement. Still, there is an opportunity for philanthropy to improve.

She says that funding with an intersectional lens in the movement looks like “creating tools for communities that have been hit hardest by Covid-19, Black, Brown, immigrant LGBTQ communities because they are the most invisible and hardest hit.” It also looks like supporting abortion access beyond the traditional constituencies of the Pro-Choice movement like “policies that protect and support trans communities of color, policies that end violence on Black communities, and ensuring that low wage workers have health and reproductive health care coverage.”

Funders risk everything by not funding reproductive justice

The importance of funding and resourcing the reproductive justice movement for the future requires looking backward in America’s history.

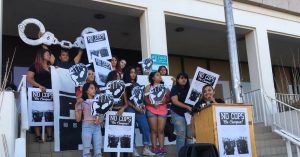

“In countries where the right wing has successfully taken over democracy, they start by attacking and focusing on reproductive justice and oppression. Throughout our history, we have seen the enslaving and sexual assault of Black women, the limiting of family formation through welfare reform, attacks on the humanity of trans and nonbinary communities, up until today, the splitting apart of families through immigration policies – these are all reproductive justice issues,” Shen explains.

This year has also seen the most attacks on reproductive access in recent years. In 2021 alone, there have been 561 restrictions on abortion access introduced on the state level, indicating that reproductive oppression is the foundation upon which agency and control are taken away from people in increasing attacks on democracy. When the insurrection took place at the Capitol in January 2021, some of the members of the riot are also well known anti-abortion activists who have been terrorizing abortion clinics for years and who also have ties to far-right extremist and white supremacist organizations.

In this context, funders risk the erosion of democracy by not funding reproductive justice. It’s time to fund reproductive justice organizations now, and with resources to sustain the movement. Beyond moving money through multi-year general operating support, funders need to trust grantees on the priorities and strategies for the movement and look beyond their typical notions of what leadership looks like and to “not just focus on the charismatic, comfortable speaking in public, leading from the front.”

By funding grassroots reproductive justice organizations, philanthropy is investing in leaders and people who create comprehensive and innovative solutions for families and communities not just for reproductive freedom, but also for economic justice, immigration justice, LGBTQ justice, and more.

RJ for the future

Shen’s 20+ years of leadership in the movement has resulted in numerous accomplishments, including expanding Asian Pacific Islanders for Reproductive Health into Forward Together. The multi-racial organization that emerged from that expansion incorporates the mind-body connection through art and movement alongside strategy planning and leadership development.

When asked about what her proudest successes over the years are, Shen points to helping the movement grow from “very, very small with low capacity to now being able to change policies at the state level, to [even] influencing the way presidential candidates in the last two elections [talk] about reproductive justice.” The investment that she and so many others over the years have made presents an optimistic future for the movement that philanthropy can contribute to.

However, in order to ensure the success of the movement for the future, philanthropy must fund BIPOC leaders intersectionally. Funders can start by talking to their grantee organizations to see how reproductive justice fits into the organization’s work, follow their lead on strategies that will work for their community, and make big investments for the future.

“We are at a really critical moment in this country where democracy is at stake for everyone,” says Shen after our initial conversation. “When you look at what’s happening in this country around the Movement for Black Lives, around the elections, the pipeline and all the work in indigenous communities, it’s BIPOC leadership at the forefront. We can’t just be fighting for the crumbs if we’re really going to make the impact that our country needs. Reproductive Justice leaders need resources and we need money to fuel the transformational changes our communities and our country needs.”

Stephanie Peng is NCRP’s Senior Associate for Movement Research and co-author of Funding the Frontlines: A Roadmap to Supporting Health Equity Through Abortion Access with NCRP’s Senior Movement Engagement Associate, Brandi Collins-Calhoun.

Click here to read more about Eveline Shen’s legacy at Forward Together.

Leave a Reply