Since 1970, the jail population in rural counties has expanded sevenfold – twice as fast as urban counties – but few philanthropic dollars go toward rural leaders tackling criminal justice reform. Last month, NCRP hosted “Mass Incarceration: The Rural Perspective” to discuss this urgent issue. Our panelists made powerful arguments for the deep potential that awaits if grantmakers confront their misconceptions and invest in the diverse leadership already hard at work in rural America.

NCRP Senior Director of Research and Policy Niki Jagpal moderated the discussion, which featured:

- Lenny Foster, director & spiritual advisor, Navajo Nation Corrections Project

- Nick Szuberla, executive director & co-founder, Working Narratives & Nation Inside

- Kenneth Glasgow, executive director, The Ordinary People Society; co-chair, Formerly Incarcerated & Convicted People’s Movement

- asha bandele, director of grants, Partnerships and Special Projects, Drug Policy Alliance

Our first panelist was Lenny Foster, who advocates for the rights of more than 2000 Native American inmates in 96 state and federal prisons, many in rural areas. He shared how Native Americans, disproportionately represented in U.S. jails and prisons, face constant discrimination once incarcerated. Prison officials routinely deny Native prisoners access to traditional cultural rites, which is in violation of First Amendment freedom of worship protections and active international treaties. Lenny and his allies at the Native American Rights Fund employ litigation, legislation and negotiation strategies to protect prisoners’ dignity and sovereignty. Lenny has seen both great success and setbacks in his decades of advocacy; stronger support from funders would help ensure that progress continues.

Next, Nick Szuberla, an award-winning producer and organizer, made the important point that those most affected by the prison system should be the ones in charge of changing it. Nick’s projects have ranged from radio shows connecting prisoners to the outside world to national campaigns on sentencing reform. He noted that low-income rural communities and urban communities of color are often pitted against each other because both lack political power. Sourcing prisoners from far-away cities has become an economic development strategy in many rural areas – but most rural people want a different future. Through storytelling campaigns and in-person gatherings, Nick sees opportunities for urban and rural communities to confront mass incarceration together. Such partnerships are deeply strategic because they are bipartisan, rooted in real people’s experiences and capable of creating a political block that outlasts precarious coalitions of D.C. power-players alone.

Rev. Kenneth Glasgow stressed the need for funders to better understand the rural South. A longtime advocate on felon voting rights, humane treatment of inmates and anti-police brutality, Kenneth directly confronted the popular myth that political conservatism makes it so “nothing can get done in the South.” He pointed out that, thanks to grassroots coalitions of rural Southern communities, over a dozen criminal justice reform laws have been passed in the South in recent years, and hundreds of thousands of formerly incarcerated people can now vote. This progress happened despite enormous opposition because of deep commitment by local advocates and immensely strong relationships that have been built over time. Sadly, these achievements rarely get covered by major news outlets or set the agenda at major funder conferences, and there’s still much work left to be done.

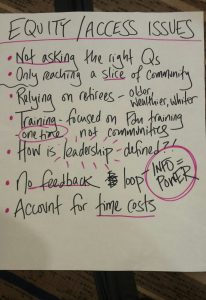

Our final speaker, asha bandele, echoed Rev. Glasgow’s call for funders and large nonprofits to ensure that resources flow toward grassroots leaders. As the manager for special grants at the Drug Policy Alliance, asha passes on dollars from DPA’s general operating funds directly to advocates like Rev. Glasgow and partners with them as they embark on their campaigns. She chastised funders for expecting people in oppressive situations to conform to their standards, rather than actually doing the hard work of making themselves uncomfortable and creating accessible spaces for the overburdened people. Too often, funders let language and protocols get in the way of funding rural advocates, instead of taking the time to meet people where they are.

In their discussion together, the four panelists agreed that there’s immense opportunity in the rural United States to change the conversation on mass incarceration. To get there, however, requires a cultural shift in the standard way of doing philanthropic business: funders should educate themselves about the culture of rural places and the ongoing work they’re unaware of, and build partnerships for the long term. In other words, good intentions alone aren’t enough.

Thanks again to all our panelists, and for those who listened in! If you missed it, catch the webinar recording, and the accompanying slides. Make sure to check out our Criminal Justice issue of Responsive Philanthropy, too, which lists case studies and resources for people working to change our justice system. And finally, let us know in the comments: What foundation action do you think it will take to bring about rural justice?

Ben Barge is a field associate at the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP). Follow @NCRP on Twitter.

CC image by Lee Honeycutt.

Leave a Reply