One of the key charges in David Callahan’s recent compelling indictment of progressive philanthropy is that progressive foundations have wasted time and money by committing to a harebrained scheme of endless program grants while their conservative opponents long ago embraced the power of general support giving.

An empire of conservative philanthropy giants “didn’t invest in issues or programs, or dole out one-year restricted grants. They invested in ideas, institutions and people. They gave general support to a core group of multi-issue think tanks, legal groups, leadership institutes, and media outfits year after year, decade after decade.”

Since we launched Criteria for Philanthropy at Its Best in 2009, NCRP has been banging the same drum on general support.

We agree that foundations who share our values of equity and justice hamstring themselves and their grantee partners when they make grants piecemeal, forcing organizations to string together a series of restricted grants while their opposition fires on all cylinders without worrying about rent, salaries or the electric bill.

The percentage of general operating support grants is the same as 15 years ago

Philanthropy’s version of the “gig economy” has bedeviled the progressive nonprofit sector for decades: Nonprofit leaders chase program grants that pay some portion of their bills – effectively serving as short-term contractors for foundations – while hoping one day their luck will break with a general support grant that gives them time and space to actually lead.

Despite what appears to be broad consensus on the value of general support grantmaking, foundation staff and executives don’t seem to be able to jump the mental, institutional or structural hurdles that prevent them from giving general support grants.

NCRP’s research shows that among the largest 1,000 foundations in the country, general support grantmaking still only comprises 20% of all domestic funding – roughly the same as in 2003 when NCRP began collecting data.

Between 2010 and 2015 (the most recent year available), the share of domestic funding given as general support declined from 25% to 20%.

The real reason foundations don’t give general support: They don’t trust their grantees

The TCC Group’s “Capturing General Operating Support Effectiveness” by Jared Raynor and Deepti Sood may offer some explanation.

While our data contradicts their assertion that general operating support has increased, their thoughtful recommendations for measuring general support impact are something we agree on: The barriers to general support grantmaking are not primarily evaluation or metrics, but trust, control and power.

Recognizing that many foundation staff cite “difficulties in measuring the impact of general support” as an excuse for not giving more of it, the authors’ goal is to “present a comprehensive outcomes framework to ground practitioners and evaluators in thinking about GOS effectiveness.”

The report outlines good reasons why evaluating the impact of general support can be beneficial to the grantee-funder relationship and provides sample indicators of impact from general support.

The report concludes: “We believe that evaluation issues should not be used as an excuse” to justify continued reliance on program grants.

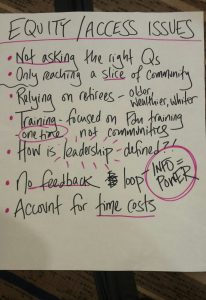

They also shouldn’t be used to mask a far knottier problem: The massive imbalance of power and trust between funders and grantees.

The report suggests sample indicators for evaluating general support impact, positive externalities that might be generated and negative externalities for funders to be wary of. The last category could mostly be grouped under the header “Loss of Funder Control.”

Examples include:

- “Over-reliance on grantee goals” (at the expense, it is implied, of the foundation’s).

- “Lack of clarity on how funds are used when integrated into the broader organization” (clarity for the funder, it is implied).

- “Complacency or reductions in urgency” on the part of grantee staff.

The report’s appendices, especially on “foundation readiness to award GOS,” are substantial and revealing. Down the line, nearly every capacity the authors suggest is some form of trust, risk-tolerance or funder accountability.

- “Foundations need enough field credibility to have the trust of grantee organizations.”

- Foundations must show a “willingness to relinquish control.”

- “Foundation program officers … need to be both a sounding board for any questions the grantee might have, and also have enough trust in the organization to allow them to maintain independence.”

- “Foundations need to be committed to supporting the grantee’s work and mission and to nurturing the relationship.”

- Foundations must adapt an “open and honest ‘learning culture.’”

The odds are against general support from the beginning

A funding decision tree provided by the authors offers some insight: 5 of 11 possible paths lead to “don’t support,” and 2 each to “capacity building support” and “negotiated general support funding,” by which they mean “general support with significant funder control.”

Just 2 of 11 paths lead to “unrestricted general support.” Already the odds are stacked against general support. The question is: Why?

While the tree’s questions begin innocuous enough, other questions with answers highly susceptible to implicit bias appear too:

- “Does the organization have strong leadership and adaptive capacity?”

- “Does the organization have a strong existing funding base?”

- “Do you want to support this organization, writ large?”

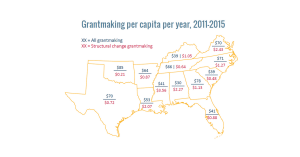

The first, as NCRP has argued in publications like As the South Grows, is too often an opportunity for white- and male-dominant, funder-centric definitions of capacity to crowd out those better suited to the context of, for example, faith organizing in rural Alabama.

The second would establish a nonprofit ecosystem where the lack of foundation support justified and perpetuated itself ad infinitum.

The third question’s meaning is vague enough to enable a plethora of biases.

Frameworks and decision trees are not a replacement for trust in grantees

These questions serve as a deadly effective filter for any potential grantee that does not have conventional (which usually means white and male) leadership; any new innovative organization without robust funding; and any organization that just “doesn’t feel right” to the foundation making that call.

The TCC Group evaluative framework is useful to those grantmakers who have already taken that “leap of faith” toward trusting that their grantees know how best to do their work.

But there isn’t a decision tree or framework in the world that can get a program officer to trust that they can let go of some of their control and still see inspiring results.

Foundation staff who recognize the value of general support in theory, but aren’t making it happen in practice, should reflect on the reasons why.

Ryan Schlegel is NCRP’s director of research. Follow @NCRP on Twitter.

Leave a Reply