Editor’s Note: On January 30, 2015 during the Florida Philanthropic Network’s 2015 Statewide Summit on Philanthropy, NCRP’s Aaron Dorfman spoke in conversation with Mark Brewer, president & CEO of Central Florida Foundation and Bill Schambra, director of Hudson Institute’s Bradley Center for Philanthropy about the tension between progressive and conservative philanthropy. The transcript of Aaron’s speech is below, beginning at 10:10 in the video.

Good morning. Thanks so much to David [Biemesderfer] and to the entire Florida Philanthropic Network for inviting me. It’s great to be here with you all today – and I’m not just saying that because it’s 50 degrees warmer here than it was in DC yesterday. I’m also saying it because you invited me to speak on a Friday and I brought my golf clubs.

But good weather and golf are not the reason we’ve come together. This state, our nation and world are facing enormous challenges. All of us who work in philanthropy are here because we hope we can do something significant to overcome those challenges.

Progressives and conservatives have a lot in common when it comes to our thinking about philanthropy’s role in a democratic society, and we also differ in some very important ways.

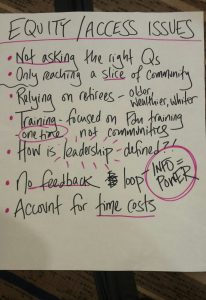

One area of commonality might be called the populist critique of philanthropy. Bill and I actually have quite a similar take on this. We both find a majority of foundations to be far too enamored of elites and out of touch with the grassroots. Complicated theories of change developed by really smart people too often prevail over the everyday wisdom and lived experiences of people in communities.

There are other commonalities, too, but I’d like to use a few minutes now to focus on some of the differences.

Most progressives believe that a robust, properly-sized and competently-functioning government sector is absolutely essential to achieving the common good. Our understanding of philanthropy’s role in society is colored through that lens, and we view philanthropy as an important complement to government. Many conservatives, on the other hand, would like to shrink government until they can drown it in the bathtub, to paraphrase Grover Norquist’s famous words. They think that private organizations, including philanthropies, are better suited than government to achieve the common good. This is a fundamental difference in how we see the world.

Bill argued that foundations have been engaging in too much advocacy. I would argue just the opposite. Foundations should be funding more advocacy, not less. If your foundation is serious about ending homelessness, or improving education, or combating climate change, or even about ensuring that the arts remain a vibrant part of the American experience, you can’t succeed in your mission without engaging in advocacy.

Why is funding advocacy essential? Because foundation spending is absolutely dwarfed by government funding.

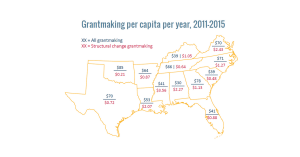

State and local governments in Florida spent $38 billion on K-12 education in the 2012-2013 school year. Philanthropy spent $41.2 million on K-12 education in FL in 2012. Which means government spent more than 900 times more than philanthropy.

A similar disparity exists for heath. Philanthropy spent $31.4 million on healthcare in 2012 while the state of Florida spent $32 billion, or about 1000 times more.

Unless foundations can influence how government functions on the issues we care about, our dollars will have little impact. We know, however, that when foundations do fund advocacy and similar strategies that it is a high-leverage investment. NCRP studies have shown a return-on-investment of an astounding $115 to $1 – for every dollar foundations invested in advocacy, communities benefited to the tune of $115. I’m sure many of you have seen those studies, but I’ll be happy to talk more about them during the Q & A period if you want. One local example is that the minimum wage just increased again here in Florida a few weeks ago. That increase, which benefits about half a million workers in the state, is the result of an advocacy campaign many years ago that was partially funded by foundations, perhaps by some of you in this room.

But contrary to what Bill asserted, very few foundations actually prioritize advocacy in their grantmaking. Only 9 percent of the largest 1000 grantmakers can be considered serious advocacy funders, meaning that they devote at least a quarter of their grant dollars to advocacy and similar strategies. In my opinion, that percentage is far too low. If we want foundations to make a more of a difference, we need to start leveraging our limited dollars by funding more advocacy.

Now let me be clear. Funding advocacy and standing for something isn’t the same thing as being partisan. Oftentimes, Democrats and Republicans are both perfectly happy to ignore certain issues or communities. Grantees who care about immigration reform have spent just as much time the past few years beating up on Democrats as they have on Republicans. Good advocacy makes government more responsive to the people. It makes government more effective, not necessarily bigger.

Given the fundamental differences in how progressives and conservatives view philanthropy’s role in a democratic society vis-à-vis government, can the sector speak with one voice on policy issues that affect philanthropy? I’m not sure that we can, or even that we should.

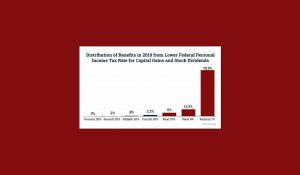

If you believe that government has a fundamentally important role to play, as I do, and that foundations and philanthropies have an important complementary role, then you’re going to evaluate tax policy proposals in their entirety, rather than just looking at how the proposal impacts philanthropy. You’ll want to know how the policy proposal impacts the issues and causes you care most about, not just how the proposal affects foundations as institutions. If a 28 percent cap on charitable deductions is part of a complex deal that will shore up the social safety net for decades to come, should we get behind that deal? Many progressives, me included, would answer yes.

Unfortunately, some in our sector believe that government is incompetent and always will be, and that private organizations are better suited to serve the common good, and their only concern with tax policy proposals is to maximize resources for philanthropy.

In the past, many associations that represent grantmakers have focused only on protecting the institutional interests of foundations. If we’re going to be serious players in debates about tax policy, however, I think we’re going to need a more nuanced position. We simply don’t have the political clout to win by taking a “hands off my deduction” position the way the NRA is able to be successful taking a “hands off my guns position.” So I think the opportunity for common ground is if we can get serious about seeing the entire forest in the tax policy debate, not just the trees that affect philanthropy. We won’t agree on everything. But I think we could find some common ground and, at the same time, increase our effectiveness with elected officials.

Thank you.

Aaron Dorfman is executive director of the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP). Follow @NCRP on Twitter.

Leave a Reply