[Editor’s Note: The following is adapted from NCRP’s Philamplify assessment, Walton Family Foundation: How Can This Market-Oriented Grantmaker Advance Community-Led Solutions for Greater Equity? This section deals with the foundation’s support of school choice and charter schools. To read the full report, click here.]

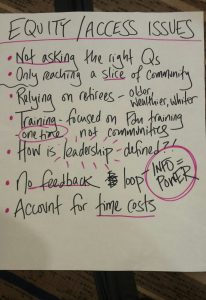

NCRP’s criteria for strategic and just impact has three key characteristics: that marginalized communities explicitly benefit, that systems become more equitable and that those most affected are empowered to help define solutions and lead the change. Further, equitable systems change means that marginalized people are able to redefine their relationship to power, institutions, and each other; it is not simply the aggregation of individual benefits.

Our Philamplify assessment of the Walton Family Foundation (WFF) found that market-based approaches, such as charter schools, can contribute to social justice outcomes, but only if they take into consideration and actively work for equitable systems change. Even those who support charters – including some peer funders, long-time grantees and sympathetic thought leaders – suggest that WFF can be more vocal in its support of quality, accountability and equity, not just for the schools it funds but in the charter school movement overall. They encourage WFF to address concerns such as the following:

Results fall short of promise. Overall nationally, charter schools have benefited some families and students, including low-income people of color in urban settings. But on the whole, charters do no better than traditional public schools, and many do worse. Even research from the charter-friendly Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) at Stanford University, a long-time WFF grantee, which has been tracking charter school outcomes over the years and released its most comprehensive study in 2013, shows mixed results. For example, only 25 percent of charter school students performed better in reading than their traditional school counterparts, with 19 percent performing worse and 56 percent performing the same. CREDO’s 2015 report claims that urban charters outperform their district peers, but this claim weakens when looking at the most marginalized students.

Lack of accountability undermines reform. While the foundation’s rigorous standards for establishing new charter schools and commitment to evaluating its portfolio are laudable and show a genuine interest in accountability, other investments contradict this stance. Thanks in large part to WFF-funded advocacy, publicly-funded charter schools have been able to carve out exemptions to the accountability and transparency mechanisms the public school system faces. While “autonomy” was meant to enable experimentation with educational design, the charter industry has taken that to mean deregulation of operations and management. Yet a recent report documented extensive fraud, abuse and waste in the charter school industry.

For-profit operators place profit before public and educational goals. Some charters have contractual arrangements with for-profit operators or facility owners, thus funneling public dollars into privately owned entities. These add further challenges to calls for transparency, because for-profits are not beholden to nonprofit reporting rules. For-profit-operated schools are under no obligation to share information about their profits, so there is no way to assess if, for example, there’s disparity between CEO salary and school outcomes.

Though the foundation says that less than 3 percent of its funding goes to for-profit-operated charter schools, WFF refuses to denounce for-profit operators of charter schools, saying the foundation is “agnostic on governance.”

Student selection often excludes those with special needs. While there is some evidence that charter schools enroll high numbers of and improve outcomes for low-income black and Latino students, there is also concern that they are underserving students with special needs. Although districts are mandated to serve all students, many charters have found ways to skirt this requirement, through mechanisms from discipline policies that push out challenging kids to communications that discourage parents of high-need students from participating.

Charter schools often leave traditional districts with diminishing resources and public support. About 95 percent of public school students are still in traditional schools. The cost of establishing charter schools often comes from public funds, drawing from the overall education budget of a district. Pulling out resources to benefit a small number of students, regardless of how marginalized and deserving they may be, can’t help but reduce resources and subsequently undermine the quality of education for the vast majority of school kids, most of whom are poor.

Privatization undermines democracy and universality of public schools. While charter supporters insist that charters are public schools, they transfer public dollars from traditional district schools to private entities to deliver public education. Equally concerning, they contribute to declining public support for and faith in public institutions.

Charter critics acknowledge that the failures, both real and perceived, of public schools are what opened up the field for this kind of approach. But they believe that strengthening the system of universal public education remains the best way to overcome these problems and inequities. A more privatized system might benefit some, but does not carry the commitment to universality that is a cornerstone of our democracy.

Parents are encouraged to behave as individually-driven consumers, fighting to get the best option for their kids, rather than champions of equity, concerned about the fate of all kids. Privatized forms of public education incentivize parents and students to act as consumers looking for individual solutions rather than citizens looking for equitable solutions, undermining what one activist called, “The best basis for social justice outcomes – getting everyone into the same pot where we all have an incentive to fully support public education.”

To read more about Walton Family Foundation’s market-based approach to education funding, read the report on Philamplify.org. And let us know what you think: Should WFF adopt education strategies that achieve greater equity? Share your answer by voting on our recommendations at http://philamplify.org/assessment/walton-family-foundation/.

Gita Gulati-Partee founded and directs OpenSource Leadership Strategies, Inc. She has written Philamplify reports on The California Endowment and Walton Family Foundation for the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP). Follow @NCRP on Twitter and join the #Philamplify conversation.

Leave a Reply