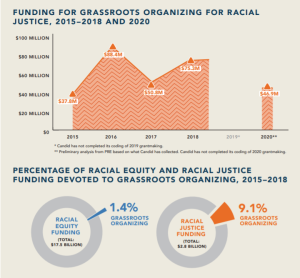

The roughly $7.9 billion injected by grantmakers into underserved communities each year has incredible positive impacts on the lives of those with the least wealth, opportunity and power. But what is philanthropy’s role in repairing a specific injustice? Can philanthropy contribute to an effort to make targeted recompense for measured, documented oppression?

In 2011, Keepseagle v. Vilsack successfully claimed the USDA discriminated against Native farmers and ranchers in the adjudication and distribution of federal loans. It was, sadly, a textbook case of racialized inequity: For decades, the federal agency responsible for distributing money to support farmers and ranchers systematically discouraged Native Americans from applying for loans. It also denied loans to Native farmers that were awarded to white farmers in nearly identical circumstances.

The $760 million settlement reached in 2010 was subjected to a round of claims, but when the claims period closed, and plaintiff debt was taken into consideration, $340 million was left on the table. After three years of debate among the plaintiffs, claimants and the federal government, it was decided the funds would endow a new foundation dedicated to improving the lives of Native farmers and ranchers.

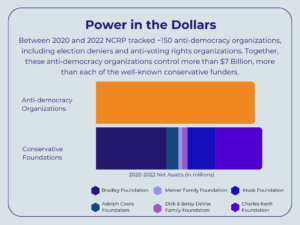

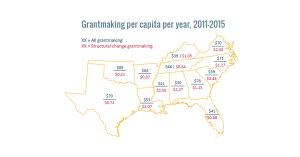

I spoke to Carly Hare, executive director of Native Americans in Philanthropy and friend of NCRP, and she shed light on how this new foundation may spark structural change. First, she reminded me that very few philanthropic dollars are devoted to Native causes and constituencies. Between 2000 and 2009, funding for Native issues and peoples comprised 0.3 percent of grant dollars nationwide, serving a community that comprises 1.7 percent of the national population and experiences some of the most pronounced poverty. What’s more, funding for Native agriculture comprised just 0.5 percent of the funds for agriculture nationally for the years data were available (going back to 2003). To say that funding for Native issues is negligible is an understatement.

Next she impressed upon me the positive steps initially taken in outlining the trust. A majority of the trustees will be Native American and they will, by and large, represent the interests and the challenges of agricultural communities in Indian Country. In our 2009 report Criteria for Philanthropy at Its Best, NCRP contended that a foundation should have a diverse board that represents the community it serves. In this case, it is important for the trust’s leadership to understand the Native American community’s concern about another federal entity responsible for patronizing Native peoples.

The trust will spend all its resources in 20 years, guaranteeing the settlement money will be used in the lifetimes of those directly affected by the USDA’s behavior, and their children’s. This choice is in keeping with a growing movement among progressive philanthropists, echoing findings in Criteria that foundations that focus on mission achievement rather than perpetuity have greater success (though, of course, there is an important place for perpetual foundations in the philanthropic sector, especially those that practice mission investing.)

Direct restitution in the form of debt relief for Native farmers and ranchers is important, but it can’t have the far-reaching, revolutionary structural effects of 20 years of targeted philanthropic investment. What’s all the more energizing, Carly emphasized, is the potential for dramatically improving the capacity of individuals and communities through the network of nonprofit organizations that currently serve this population – many of them led by Native people with first-hand knowledge of the issues. If the money is disbursed strategically, it could water the seeds of nonprofit infrastructure that will grow to benefit Native farming and ranching communities for generations to come. If the trust fund was visionary in its goal setting, Carly continued, it could make headway on complex, nebulous issues directly related to poverty in Indian Country:

- Capacity of Native farmers and ranchers to seek and secure resources.

- Advocacy for Native agriculture interests at local, state and federal level including the all-important farm bill.

- Sustainability of traditional farming and ranching practices and systems.

- Improved access to quality agricultural education at tribal colleges and universities.

- Access to healthy foods.

- Growth of locally grown, organic food infrastructure, a potential economic engine.

It is, unfortunately, rare that such targeted means to structural change are ever seriously discussed in our country, and rarer still that social justice advocates are given the chance to see a recompense process through. The opportunity for deep, long-lasting change to unjust systems in Indian Country represented by the establishment of the trust deserves attention, support and partnership from the philanthropic community. With careful planning and attention to the values of strategic, equity-driven, responsive philanthropy, the trust can be both a major force for good and a model for change in the coming decades.

My thanks and appreciation to Carly Hare for her assistance with this piece and for her continued hard work on behalf of social justice.

Ryan Schlegel is research and policy assistant at the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP). Follow @NCRP on Twitter.