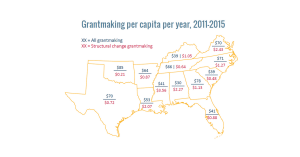

NCRP’s work in the philanthropic sector urges grantmakers to prioritize those with the least wealth and power in society. Often that means persuading foundations to intentionally target their investments to benefit people of color, poor people, recent immigrants and refugees and other marginalized groups. NCRP’s nationwide focus recognizes that systemic deprivation and oppression are not evenly distributed: some regions and states have pockets of concentrated poverty and disenfranchisement.

JustSouth Index 2016, a recent report from Loyola University in New Orleans, illustrates this point well. The university’s Jesuit Social Research Institute found that on measures of poverty, racial disparity and immigrant exclusion, the five Gulf Coast states fare particularly poorly. The report is unsparing in its portrayal of a part of the South that continues to struggle with a long history of regressive economic policy, racial exclusion and entrenched poverty. The JustSouth Index utilizes a set of six indicator values, three each for the categories of poverty, racial disparity and immigrant exclusion. The indicators were chosen, the authors point out, because they are “clear, reliable and actionable.”

Indeed, the indicators point to some of the most deeply systemic issues facing Southerners in the 21st century: some of the lowest-in-the-nation household incomes, lack of health insurance coverage, segregated — and segregating — public schools, racial income inequity and the forced isolation and disconnection of recent immigrants. These problems are not unique to the South, but their most extreme expression can often be found there.

Although the authors call the index indicators actionable, the report contributes little to outlining context-specific action items for each. In other words, taking action on the gap in unemployment between white and non-white workers by “creating equal access to quality public education for minority children” makes sense in theory, but the report stops short of explaining the particularities of educational inequity in the South, nor does it point out the work already being done on this issue by Southern advocates. I think that the report could have benefited from an explanation of the challenges of educational access and equity in the South paired with a profile of grassroots efforts underway already would have readers with an opportunity to engage more deeply with that work. It could have provided “guidance regarding how citizens and leaders in the Gulf South can change this picture” of injustice, as the introduction stated.

I realize that the JustSouth Index 2016 sets out to be “a strong starting point” for addressing inequity in the South. And the report excels at framing the issues of poverty, racial injustice and immigrant exclusion as exactly what they are: policy choices. The lack of a living wage in the Gulf South states, the refusal to expand Medicaid, the resegregation of public schools, the lack of access to public services for immigrants; each of these is a policy choice made at the state and local level.

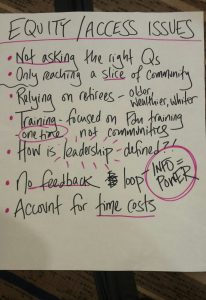

This is the “strong starting point” the philanthropic sector needs: The only way to achieve lasting change on issues of economic, racial and social justice will be with advocacy, organizing and, eventually, policy changes. Institutional racism is a gargantuan barrier to success for people across the country and the South. Foundations that care about equity and justice – especially in these Southern states – ought to invest in strategies to affect the machinery of policymaking that lets these conditions persist.

If the philanthropic sector hopes to have a role in moving the needle on important indicators of social justice, we need to find, highlight and invest in the South’s assets, not just point out its deep flaws.

And foundations also need to remember, as they approach their work in the South, that context – be it social, geographic, racial or cultural – matters, perhaps nowhere more than in the South. A history of systemic underinvestment from the philanthropic sector in the South can change – it must change. But it has to change on Southerners’ terms if it is to lead to lasting progress in the South that benefits all residents.

In 2017, NCRP, in partnership with Grantmakers for Southern Progress, will debut new research on this very question: How can foundations engage in the South so that more dollars will be invested in Southern communities that need them most, and so that the outcome of these investments will be equitable and sustainable? How can the philanthropic sector turn away from a history of fraught relationships with Southerners toward powerful relationships that benefits both funder and grantee? GSP and NCRP will build on the work of the Jesuit Social Research Institute and others who have examined entrenched inequity in the South to present the region in a new light.

The South is a place of opportunity for great change, a place with deep reserves of social capital and a history of world-changing social movements. If the philanthropic sector recognizes that reality, the South has great potential to address its unjust economic, social and racial systems and once again lead the country in a movement for justice.

Ryan Schlegel is senior research and policy associate at the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP). Follow @NCRP on Twitter.

Image by Mark Brennan, modified under Creative Commons license.

Leave a Reply