I was born in the U.S. to Jamaican immigrants and raised in Brooklyn, New York, in one of the largest West Indian immigrant communities outside of the Caribbean.

I was fortunate to attend public schools that reflected my cultural background and that of the diverse community I lived in. I was taught to embrace my dual heritage without fear or shame, and to embrace the diversity of my classmates, my community and my country.

Only 37 years ago, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Plyler v. Doe that a public education could not be denied on the basis of immigration status. They cited education as a primary means of instilling “the values on which our society rests.” I agree.

But what are those values now when hostile immigration policies derail learning for K-12 students, reinforce barriers to higher education and threaten the progress of immigrant families?

For millions of immigrants in mixed status households the ruling is an empty promise.

It seems there’s an implicit understanding in education philanthropy that education justice cannot be divested from its intersections with language, culture, race and immigration status.

A recent survey suggests education philanthropy has shifted focus from K-12 academics to strategies that support the social, emotional and cultural needs of all students.

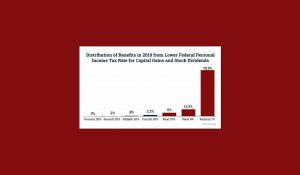

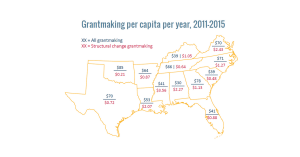

But according to NCRP’s Movement Investment Project report on the State of Foundation Grantmaking for the Pro-Immigrant Movement data show that most of the support for the pro-immigrant movement went to policy advocacy and litigation organizations, and that total funding for the movement is less than that for leisure sports.

Funding for immigrants and refugees represent barely 1% of total funding from 1,000 of the largest U.S. foundations between 2011 and 2015, and 11 funders provided half of all pro-immigration movement funding between 2014 and 2016.

As anti-immigrant rhetoric spurs violent attacks on immigrant communities and families are torn apart, it’s imperative that philanthropy see that investing in the needs of whole learners means recognizing the needs of immigrant students.

Immigrant justice is an education issue.

One in 4 children attending U.S. public schools live in immigrant households. Seventy-two percent of U.S. born and naturalized children live with at least 1 undocumented parent.

One million children in the U.S. are undocumented, and nearly 100,000 undocumented students graduate from the U.S. high schools annually.

Education funders undoubtedly serve immigrant communities even if they do not necessarily consider themselves immigrant justice funders.

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has stoked fear within immigrant communities for the dehumanizing treatment of undocumented people held in detention centers and family separations at the border.

Immigrant students regardless of legal status have reported fearing that they or a loved one may be detained by ICE agents.

Fears of deportation have contributed to: poor academic performance; anxiety and behavioral issues; and fluctuations in student attendance.

Perhaps the most devastating blow dealt to immigrant justice and public education was the rescission of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), the Obama-era pro-immigrant policy that offered deportation protection, driver’s and occupational licenses, work permits and higher education opportunities for more than 700,000 immigrants including 20,000 educators across the country.

Costs of college tuition places higher education virtually out of reach for the 30% of immigrant families living below the federal poverty line.

Few states offer in-state tuition or state funding to undocumented immigrants, and, when they do, it is an extension of pro-immigrant policies such as DACA. Undocumented students do not qualify for federal aid.

These barriers to education equity are antithetical to the promise of justice and opportunity for immigrant children upon which Plyler v. Doe was decided. Lifting these barriers should be a high priority for education funders committed to an education system that serves all students.

How education funders can support undocumented immigrant students

The variables affecting educational outcomes of immigrant communities should directly inform grantmaking strategies that are intended to support the whole learner.

Here are 3 steps funders can take to be more responsive to the needs of immigrant students and communities:

1. Support the efforts of schools to protect undocumented students.

In response to ICE’s law enforcement practices school leaders have partnered with local nonprofit organizations such as Immschools to be more responsive to the challenges posed to immigrant communities and the students they serve.

Find out how you, as a funder, can collaborate with organizations on the ground who are empowering these schools to safeguard the education of all their students. It’s imperative that these schools have the resources they need to legally support and advocate for their immigrant students.

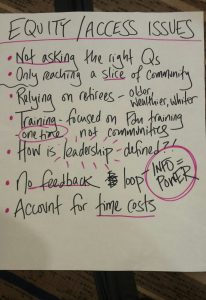

2. Give long-term flexible and capacity building support to frontline groups.

Grassroots organizations and advocacy groups are the first line of defense for immigrant communities at risk but they are largely underfunded.

Invest in capacity building and immigrant-led organizing in the most at-risk areas so these groups have the resources to mobilize communities navigating the volatile landscape of immigration status.

3. Invest in the pro-immigrant movement beyond grantmaking.

The pro-immigrant and -refugee movement need voices as much as they need funding. Leverage your organizational resources to make space at the table for immigrant movement leaders.

Speak out against deportations that dismantle families, make sure your investments do not support immigrant detention centers and surveillance, and call on your peers to do the same.

Support the pro-immigrant movement groups in accessing 501(c)4 funds

The future of immigration reform in the U.S. depends on informed voter decisions. Even with limited capacity and resources pro-immigrant organizations have shown they can make great strides in promoting pro-immigrant candidates for elected office.

With access to 501(c)4 funding the organizations will have greater flexibility to lobby for and against legislation, distribute voter guides that compare candidates based on their immigrant stances and organize voter registration drives.

The Jamaican national motto says “Out of many, one people” in celebration of Jamaica’s multicultural roots.

The U.S.’ de facto national motto is the Latin “E pluribus Unum,” which translates to “Out of many, one.”

My heritage is a reminder that there is strength in diversity, and what threatens the stability of immigrant communities threatens all of us.

I challenge education philanthropy to consider the needs of our most vulnerable immigrant communities and support movements led by and for those on the frontlines.

Nichia McFarlane is NCRP’s events intern. Follow @NCRP on Twitter.

Image by Molly Adams. Used under Creative Commons license.

Leave a Reply