In a recent critique of commercial gift funds (sponsors of donor-advised funds affiliated with financial industry giants like Fidelity, Schwab and Vanguard), Drummond Pike suggests that “Anyone who thinks any of these institutions decided to start offering donor-advised funds purely from a desire to prompt more giving to nonprofits needs a lesson in altruism.”

Pike, founder and former CEO of Tides Foundation, goes on to recommend that “DAFs should be treated with rules mirroring those applied to private foundations,” and that “charities should be expected to use objective, transparent standards and commitment to the public good in the management of their assets.”

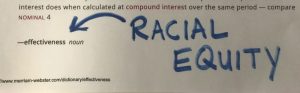

Many of the suggestions for ensuring greater transparency and accountability make good sense. But at the end of the day, if we really want to address the rapidly increasing inequitable accumulation of wealth, we need to take a much broader look at tax policies than just those governing what donors can or cannot claim as tax deductions for charitable giving.

In other words: Follow the money.

DAFs, Big philanthropy and the tax system

Not a few of the criticisms aimed at DAFs could be applied equally to problematic practices and perquisites inherent in Big Philanthropy as a whole, which a slew of thought leaders and journalists – the Institute for Policy Studies’ Chuck Collins, Helen Flannery and Josh Hoxie, the New Yorker’s Elizabeth Kolbert, Rob Reich and Anand Giridharadas to name a few – have detailed extensively of late. Such critiques aren’t new: NCRP’s emerita board member Terry Odendahl wrote incisively about this in her 1990 book, Charity Begins At Home: Generosity And Self-interest Among The Philanthropic Elite, which argued that “philanthropy is essential to the maintenance and perpetuation of the upper class in the United States.”

The increasing popularity of DAFs is due in large part to the tax breaks they give donors relative to other forms of giving, and the benefits of those breaks only multiply the higher you go up the income wealth ladder. But, ultimately, the advantages that distinguish DAFs and philanthropic giving in general rest on wider privileges built into the tax system as a whole.

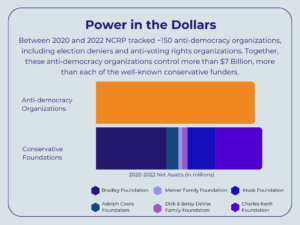

The assets in DAFs are indeed growing at a good clip. But the amount of wealth piling up in these funds barely registers in comparison with the trillions of dollars that the wealthy accumulate – and all too often shield from taxation – that are not sitting in charitable accounts. Vanguard, Schwab and Fidelity have nearly $11 trillion in assets under management on their for-profit sides, compared to the roughly $35 billion in the donor advised funds they manage.

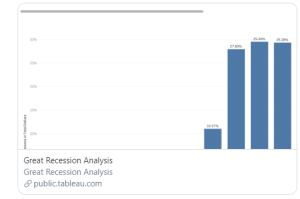

Or take a look at the big picture on capital gains, which are taxed at 20 percent – a substantially lower top rate than the 37 percent rate for ordinary income. Economists project that as a direct result of the preferentially lower tax rates for capital gains and stock dividends, the country will lose an astounding $152 billion in tax revenue for 2019.

What role do DAFS play in this picture? The National Philanthropic Trust’s most recent (2017) report shows some $23 billion donated to DAFs in the last report year. If 30 percent of that figure represented otherwise taxable long-term capital gains, the amount of uncollected capital gains taxes would be approximately $1.4 billion or less than 1 percent of the total loss.

Seen in this light, a narrow effort to push DAFs to revert to prevailing philanthropic norms seems insufficient to the enormity of the task at hand.

Inequitable tax system: the elephant in the room

The bottom line is that a discussion of DAFs inside the philanthropic community that fails to look at much greater inequities baked into the tax system as a whole leaves the proverbial elephant planted squarely in the middle of the room.

The sector would do well to look not only inward, but also outward as it seeks to address the scourge of wealth concentration and inequality in our new gilded age.

Dan Petegorsky is senior fellow and director of public policy at NCRP. Follow @ncrp on Twitter.

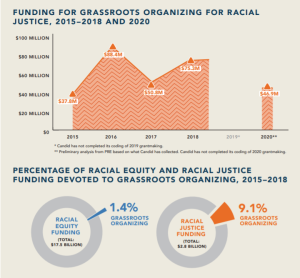

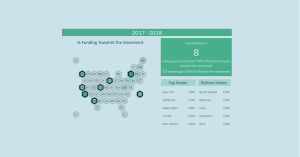

Image courtesy of Steve Wamhoff, Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP)