Every summer for at least 15 years of my life, my siblings and I were shipped to Bowling Green, Kentucky, to spend time with our grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins. We spent hot days on the farm, in town, at the public library or at church.

A highlight for me was helping my aunt set up her third grade classroom for the new school year!

Those summers created a love for teaching and a career in education that has led me to the Southern Education Foundation (SEF), where I’ve been the vice president for just over two years.

I have lived in Atlanta for 10 years. After spending a significant part of my childhood in the South, I am now raising a son there.

SEF, with origins to 1867 and the George Peabody Education Fund, is a historic nonprofit whose mission is to advance equity and excellence in education in the South for low-income and minority students.

We support networks of school system leaders and advocates as they work to advance education justice agendas across the South through direct engagement to educate and organize.

We provide research, tools and, in some cases, capital assistance to organizations for advancing education through policy and practice reforms that improve learning opportunities children of color.

As stated in As the South Grows: Bearing Fruit, poverty is a product of structural inequality, racism, discrimination and the disinvestment of social safeguards like public education, health care and services that protect marginalized and vulnerable people.

At SEF, we believe that we have to do more to address these realities in the American South, especially the Deep South.

A big challenge in this work is the view among some policymakers and community leaders that there is little that can be done about poverty — that the problem is largely one of personal responsibility.

SEF rejects this premise and points to the overwhelming evidence that education is a key driver of upward mobility. Accordingly, SEF believes investing in education is one of the most powerful strategies to combat poverty in the region.

We are challenged by how to help public schools address the implications of poverty for student learning and development.

Much of the preceding decade has been witness to reform strategies that have taken poverty off the table.

With little evidence that governance reforms (e.g. charter schools) and accountability measures (e.g. more testing and teacher evaluation) have had an impact on learning outcomes for poor children, there is growing recognition that broader and bolder strategies are need to close these achievement gaps.

The good news is that in addition to emerging evidence on effective strategies, we have more examples to bring forward on how our education system can meet the needs of the whole child by providing the wraparound supports children from more advantaged households take for granted.

Education is an intersectional issue. All of the issues raised in Bearing Fruit – health, housing, economic developmental, environmental justice – affect the education of our children.

Family income is a proxy for a range of conditions and circumstances that shape the daily lives of students.

We know that children from low-income families more often endure acute illnesses that lead to chronic absenteeism and lost instructional time.

We know that students who fear deportation, racism or violence cannot concentrate in school.

We know that housing status affects the resources that neighborhood schools receive.

So we need to figure out ways to forge more effective collaboration and coordination between these sectors.

Strategies like community schools provide an infrastructure for schools to better serve and be served by their communities, leverage their assets and find ways to build cross-sector collaborations so that students receive what they need so they can be ready to learn.

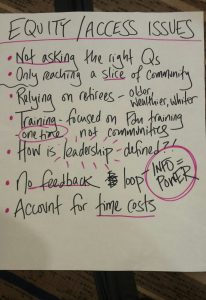

More broadly, we are struck by the need to build stronger infrastructure among the organizations in the South that advocate for children and youth as part of their efforts to support low-income families and the disadvantaged.

The energy, passion and determination to do their work is clear. But opportunities for personal renewal, sharing stories and strategies are infrequent.

And, while many of these organizations have bench strength on which they can draw, they do not have the necessary financial resources to sustain their leadership structures.

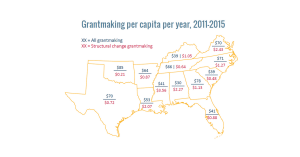

Moreover, while significant grantmaking dollars are invested in education, particularly in direct services, I wonder what would happen if funders invested in human-centered strategies like creating real space for parents, students and community members to advance their vision for a quality educational experience.

What could we learn from listening to their hopes, dreams and aspirations?

Leah Austin is SEF’s vice president of programs. Follow @SouthernEdFound on Twitter.

Leave a Reply