“If you have come here to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.” – Aboriginal activists group / Lilla Watson, Queensland, 1970s

Funders that care about health equity have come a long way in the last 20 years. They increasingly emphasize social determinants of health, think intentionally about how to work with communities, and want to make sure those relationships are more authentic and driven by community priorities.

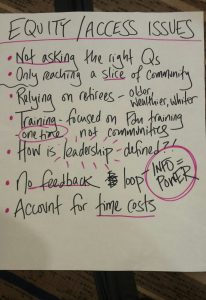

The next frontier for health philanthropy is to squarely name and redress power imbalances and systems of oppression – racism, sexism, xenophobia, homophobia and ableism – at the root of health inequities.

A recent blog post in Health Affairs posed the question: “Power: The Most Fundamental Cause of Health Inequity?” The authors state:

Addressing the social determinants of health – at least in the manner that they have been conceptualized and measured to date – alone will not support our nation’s efforts to reach our health potential … It is time to address power … Advancing equity, therefore, requires attention to power (as a determinant) and empowerment, or building power (as a process).

We’ve been more explicitly naming the centrality of power in our work to advance health equity at Human Impact Partners (HIP):

- In our research and advocacy we work directly with community organizers, who have a keen analysis of power and are committed to building power in communities.

- In our capacity- and field-building, we’re developing a stronger social justice identity and practice within public health, and building bridges to connect the public health sector to community organizing.

- In diverse settings we unapologetically advance our perspective, including in government and other institutions that have been complicit in creating inequities.

So what would it mean for health funders to focus on power? We’ve learned much from the incredibly inspiring approach of The California Endowment. As we’ve experimented with this question, we offer a few ideas for funders to consider. While some ideas are primarily relevant to health funders, most are applicable to any grantmaker that is working toward equitable, thriving communities.

1. Develop a theory of change that includes how power and oppression constrain – or support – policy, systems and environmental change.

To eliminate health inequities at the root, funders should develop an analysis and understanding of how power is at play – currently and historically – in the issues they care about. Consider housing: Access to affordable, safe housing is unquestionably a determinant of health. But why is housing so unaffordable and of such poor quality in certain neighborhoods?

I think about our social and political history, and how redlining and housing covenants kept people of color in racially and economically segregated communities. This is just one example of how public policy was actively manipulated by those in power to physically and emotionally marginalize people of color and poor people. This pattern repeats itself across issues health funders care about, from education to employment to the environment.

Developing an analysis of power is essential to break these cycles and be realistic about what it takes to achieve social determinants of health policy change – where the status quo is often entrenched and resistant to change. Having this analysis would help funders widen the type and scope of interventions and strategies they consider funding and potentially be more successful at advancing health equity.

2. Learn from, ally with and support those who believe in power-building to make headway on the issues you care about (read: work with community organizers).

Mindset shift is essential. Health funders need to see themselves as part of a larger social justice fabric where their health identity aligns explicitly with social movements. This means learning from and supporting foundations and organizations that focus on building power and see themselves as part of the same ecosystem. Health funders could directly support power-building by funding grassroots movements and organizations, to advance solutions to the problems communities identify.

Community organizers may not necessarily see health as a top challenge and may not lead with it. Health funders would have to grow comfortable funding organizations that never talk about health. They would have to trust that grassroots organizing for policy, systems and environmental change around the social determinants has downstream benefits for health and equity.

3. Uphold a narrative within health philanthropy that’s about building power to advance health equity, which acknowledges entrenched systems of oppression.

Developing an analysis is not enough. Narrative change within health is daunting but needed. Narratives are values-based stories about how and why the world works as it does, which frame our responses to the problems we see.

Funders must actively hold each other accountable to change entrenched narratives that impede progress on health equity. They must tell the story of how power imbalances and oppression created unfair and unjust systems that led to poor health and persistent health inequities.

Importantly, the narrative cannot be based just on numbers and facts – we also want to activate hearts and minds by centering people who have been harmed by racism and other forms of oppression. This can happen through listening, storytelling, examining our history and owning our piece of it.

4. Create a framework for measuring outcomes and progress. Fund the development of appropriate metrics for organizing and advocacy that advances health equity.

I’m incredibly proud of our progress, but I can’t necessarily tell you how we’ve changed health outcomes yet. I’d love to have health funders’ energy and support in defining success, which includes process metrics about developing transformative relationships, changing the conversation, developing leaders and innovating around strategy.

Most recently we’ve seen the potential of this approach in Massachusetts, where a new criminal justice law expands the use of alternatives to incarceration for parents of dependent children. Formerly incarcerated women from Families for Justice as Healing wrote and advocated for the “primary caretakers” provisions, and our team at HIP wrote a report on the health impacts of the policy and educated public health stakeholders, who rallied behind it.

This successful collaboration, with research funded by The Kresge Foundation, came about because HIP explicitly names the centrality of power in advancing health equity.

The shift to a social determinants frame in health philanthropy was a huge accomplishment. Given the wider reckoning in our society, we can’t wait another 20 years to explicitly name power and oppression’s role in creating health inequities. Let’s get clear on these root causes and shift the conversation, and our efforts, to challenge them. Only then can we be confident that we’re truly creating a society in which everyone can thrive.

Lili Farhang is co-director of Human Impact Partners, which brings the power of public health to campaigns and movements for a just society. Follow @HumanImpact_HIP on Twitter.

Leave a Reply