Grantmakers are able to grow movements by focusing on the entirety of issues, cultivating public support, funding effective nonprofit change-makers and growing political pressure through advocacy. These strategies allow grantmakers to leverage their limited resources to effect lasting change. For this reason, it is important for foundations to listen to the voices of those they serve to ensure that the change they create is in line with the values of the community.

Take the charter school movement in education: What originally began as a model popularized by Albert Shanker, President of the American Federation of Teachers, to incubate educational innovation has since morphed into a bastion of market-based education reforms based on accountability and choice. Shanker was an early advocate for charter schools, viewing the flexibility inherent in the model as a way for teachers to experiment with better ways to reach students. These schools would be test kitchens of sorts, sending along their best recipes to the public schools. Shanker envisioned that there would be a good amount of interaction between the traditional public schools and the charters, as each worked together to improve student outcomes.

The charter schools of today have deviated from Shanker’s original vision. Instead of fostering collaboration between charter schools and traditional public district schools, the movement has pitted the two school options against each other. As Richard Kahlenberg and Halley Potter from the Century Foundation wrote recently for The New York Times:

“Over time, however, charter schools morphed into a very different animal as conservatives, allied with some social-justice-minded liberals, began to promote charters as part of a more open marketplace from which families could choose schools. Others saw in charter schools the chance to empower management and circumvent teachers unions. Only about 12 percent of the nation’s charter schools afford union representation for teachers.”

Philanthropic dollars have altered the education space, increasing competition for resources and students between different types of schools. Some of the biggest foundations in the United States contributed in part to this shift. While dollars are limited and philanthropic dollars in support of education are small in comparison to government spending, foundations have been integral players in introducing market-based reforms to education. This group, comprised of large foundations and hedge fund managers alike, has worked to grow a movement supporting charter schools. They have supported public policy advocacy, garnered public support and have pooled private dollars into funding charters. This trend has vastly changed the way that students experience the educational system in the United States. As the charter movement demonstrates, grantmakers have the power to be game changers. They can direct funds to grow nascent fields, pull away resources from other areas and even shift policy debates and outcomes.

This focus on reforming the educational landscape does not necessarily prioritize the needs of marginalized communities. Of the 672 education funders surveyed in NCRP’s Confronting Systemic Inequities in Education report, only 11 percent gave at least half of their education grant dollars to support marginalized communities and 2 percent gave at least 25 percent to support systems change strategies. The challenges present in the educational landscape are systemic and disproportionately affect students and families with marginalized identities. To create change, grants must match these needs and target the systemic challenges that underserved students face.

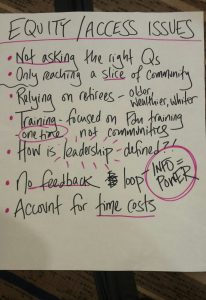

In the current reality of many nonprofit and advocacy organizations surviving mostly on grants from philanthropic institutions, grantmakers have the power to determine which organizations and issue areas receive the most lucrative support, while others struggle. We must look critically at the power that foundations have, especially in light of the Center for Effective Philanthropy’s most recent report, “Hearing from Those We Seek to Help,” which found that “nonprofit leaders believe most of their foundation funders lack a deep understanding of their intended beneficiaries’ needs.” Is philanthropic decision-making rooted in what is best for the people who need the support the most? And perhaps most importantly, in developing their strategies, does philanthropy seek to engage people directly affected by our most pressing social problems?

There is a grassroots movement gaining steam in many communities that is pushing back against the rise of charter schools. Educators fear that building more charter schools is too expensive, while others think that the competition between schools does not actually drive the overall system to improve. Many parents question whether charter schools are the best option for their children. This movement is described in greater detail in “Organizing for Educational Justice: Parents, Students and Labor Join Forces to Reclaim Public Education” by the Alliance to Reclaim our Schools.

When money is spent to improve our society, it must be rooted in the needs of the communities it seeks to serve and in what communities identify for themselves as solutions to the problems that affect them the most. As long as the chasm between foundations and beneficiaries continues to exist, money will be linked to power. Let us know in the comments: How can money best be used to bestow power upon underserved communities, instead of reflecting that of the donor?

Lia Weintraub is field assistant at the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP). Follow @liaweintraub and @NCRP on Twitter.

Leave a Reply