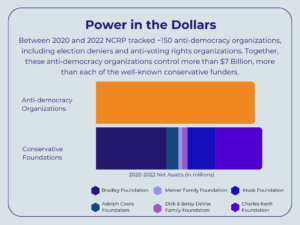

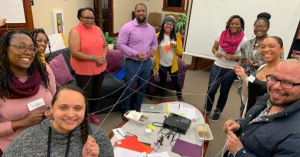

In April, NCRP launched the Movement Investment Project, a new initiative to help foundations and donors better connect their resources with grassroots movements for social justice.

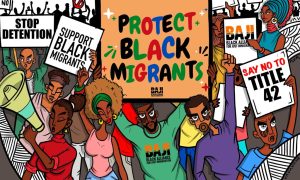

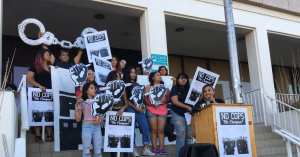

This year the Movement Investment Project is focusing on the pro-immigrant movement at a time when the safety and prosperity of new Americans is under significant threat.

As the child of immigrants, the movement is personal to me. There are many kinds of migration stories – many families have one – but this is mine.

My parents came to the U.S. from Taiwan in the early 1980s, newly married and ready to take on a new country, language and culture.

They settled in a small, predominantly white town in rural New Jersey to raise their children, away from a town with a tight-knit Chinese community and surrounded by the American culture that they were still trying to understand.

When my brother was in elementary and middle school, he was the town’s Asian population. When I went through the school system several years later, I was still only one among a handful.

Some of my teachers didn’t know where Taiwan is, and more than a few teachers were disappointed that math and science were not my strengths.

Our story is not unlike many other Asian immigrants and their American-born children who immigrated to the U.S. after 1965.

But to start the Asian American immigration story at that point in American history is an injustice to the much longer story of the Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) community in the country.

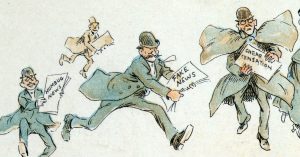

The first immigration legislation passed by the U.S. Congress (in 1882) was the Chinese Exclusion Act. And from 1924 until 1965 – when Congress passed the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 – all immigrants from Asian counties were banned from migrating to the U.S.

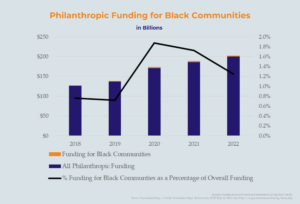

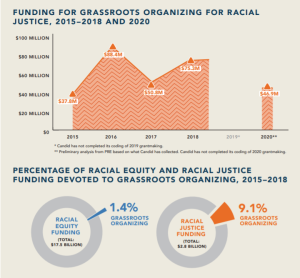

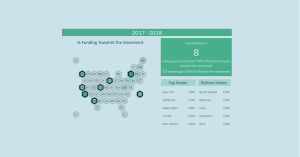

Fast forward through many migration stories like my parents’ to 2016, when only 4% of the $129 million U.S. foundations gave to support immigrant rights work was for AAPI communities, which make up 27% of the immigrant population.

This AAPI Heritage Month, it’s time to recognize that philanthropy has an Asian American exclusion problem.

As foundations and donors begin to think about how better to support the pro-immigrant movement, philanthropists should be especially mindful of how better to recognize the complexity of the AAPI community and support its leaders.

They can start by recognizing the long history of Asian immigration in the U.S., the diversity of AAPI communities and the powerful potential for movement leadership we bring to the table.

The AAPI community is not a monolith.

The AAPI community is remarkably diverse – 94% of the AAPI population in the U.S. comes from 19 different origin groups.

But the broader AAPI community has origins in Sri Lanka, the Marshall Islands and everywhere in between with countless languages, cultures and histories.

The diversity is often hidden and lumped together by media, researchers and philanthropy. Throughout history, people with AAPI identities have been laborers, refugees, business owners, enemies and the “model minority,” often all of the above simultaneously.

Aggregated statistics point to the AAPI community as one of the most prosperous minority groups in the country with higher median incomes and higher education attainment than the national average.

Disaggregated data shows that certain subgroups of AAPI people are also among the lowest-educated and lowest on the income brackets.

Treating the AAPI community as one community with the same needs and solutions only perpetuates the history of racism, discrimination and erasure against us.

Philanthropy can support AAPI leaders so that we are no longer excluded.

My parents and the immigrants that came before and after them all seek a better future and an opportunity to be happy and prosperous.

Any many of us – whether recently arrived immigrants or descendants of immigrants – are still figuring out how to navigate American society while honoring the cultures and histories of our families.

Whether we arrived yesterday or 40 years ago, we are changing our communities and the makeup of the country.

My high school now has a Mandarin program, and there is a growing community of Chinese people in my town – a sign that the AAPI community is projected to become the largest minority group in the U.S.

Philanthropy can invest in a future that celebrates the diversity of the AAPI population.

Here are some ways to start:

- Understand how the racism and exclusion of the AAPI community has occurred throughout American history. Learn how that history has affected how the AAPI community is represented today and how it connects to your own funding priorities.

- Disaggregate the data. What are the disparities among the different AAPI communities where you fund? What disparities exist between states with different AAPI populations?

- Support AAPI-led pro-immigrant, advocacy and grassroots organizations. They are the ones who know the experiences of their communities the best, and increasing support for these organizations can be a powerful start of long-term change for the whole movement.

- Include AAPI voices at the table. Make sure that the AAPI community and the diversity of their experiences is included in conversations about strategic priorities or grantmaking decisions.

In this critical time of increasing attacks and threats against all immigrant populations, philanthropy can support the AAPI leaders who are trying to make our voices heard and make sure that we – and all other immigrants – are no longer excluded from being part of America’s story.

Stephanie Peng is a research and policy associate at NCRP. Follow @NCRP on Twitter.