Updated 6/6/19.

“Why would we ever leave?” That was a sentiment I heard over and over from my cousins and friends when I returned to Venezuela every summer as I was growing up.

There was a sense that Venezuela had everything you would ever want. Maybe, back then, it did.

Unlike most people of my generation, I did leave Venezuela, back in 1985 when my family moved. We didn’t think we’d be gone long, just a couple of years in the U.S., where we’d learn English and then come back. We left with our return very much in our minds.

For many years, my sisters and I would spend summers back in Barquisimeto, where I was born and where my grandmother, cousins and friends still live.

I even spent a semester of college there, right around the time that Hugo Chávez was first elected president. Barquisimeto was a thriving place then, the 4th largest city in Venezuela, 225 miles west of Caracas.

It was an important industrial and commercial center, surrounded by productive farmlands, including the small corn and pineapple farm where I was born.

From then to now: A great decline

A great deal has changed over the years. Although I remember Barquisimeto as a booming industrial city, a number of pervasive factors, including corruption, economic instability and widespread crime, has left Barquisimeto, like the rest of the country, in ruins.

Venezuelans today live in crisis. The economy has collapsed, precipitated in part by falling oil prices and sanctions and the flight of foreign investment.

People often find themselves without basic necessities, like drinking water, food, medicine, sanitation and electricity.

The average Venezuelan has lost 24 pounds since 2017. Extreme hyperinflation – estimated at 80,000% in 2018 – has curtailed Venezuelans’ abilities to purchase anything.

What’s more, President Trump’s sanctions contribute to this dire situation, decreasing food access along with increased displacement, disease and death.

I’ve witnessed this disaster from afar, as portrayed in the news, and also from the WhatsApp messages and phone calls from my family.

My grandmother is now 91, and my cousins struggle to meet her medical needs. They tell me about power outages, living without running water for days.

They ate only arepas for several days, because there was nothing else. My family in the U.S. has sent money and tried to ship goods through private couriers, but almost nothing gets through now.

As a result, family and friends in Venezuela have started to wrestle with difficult choices. Several have already left the country, which is often an extremely difficult bureaucratic process and often dangerous, arduous journey. But they have no other choice.

It is estimated that 3.4 million Venezuelans have fled the country since 2014 – almost 10% of the population.

Many make their trek by foot with little or no money in hand, and face discrimination or even violence from the communities where they seek to find a job and start over.

Although Venezuela was once the receiving country for many of the region’s refugees, a reverse flow of approximately 5,000 migrants and asylum seekers per day now flee to neighboring Colombia, as well as to Brazil, Ecuador and Peru.

Nonprofits and local governments are doing their best to provide shelter, food and other basic necessities, but, in many places, migrants are straining resources. In places like Peru, xenophobia and fear have led some municipalities to shut their doors to new Venezuelan arrivals.

The philanthropic response isn’t meeting the need.

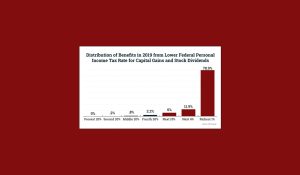

The philanthropic response1 to this crisis has been insufficient, compared to other recent global refugee crises. Venezuela is second only to Syria in terms of numbers of displaced persons living outside their country of origin (6.3 million, versus 3.4 million).

The global philanthropic response to the Syrian refugee crisis (including foreign aid and private grants/donations) has been much larger: $34.6 billion, versus $163 million for Venezuela.

Even using generous estimates for donations in 2019, all of this translates to more than $5,000 in aid per Syrian refugee compared to less than $300 per Venezuelan refugee, according to the Organization of American (OAR) States Report, 2019.

And the OAS predicts that the number of displaced Venezuelans could reach as high as 8 million by 2020.

The philanthropic community – including institutional and individual donors – can do better. That’s 1 of the reasons that Hispanics in Philanthropy (HIP) is collaborating with funders to explore how the sector can better support the migrants fleeing Venezuela.

HIP has a strong history of work on migrant and refugee issues. HIP works across the Americas to support migrant communities, by leading strategic grantmaking initiatives and educating funders and the wider public about the needs and realities of migrants.

Our work in recent years has primarily focused on humanitarian and legal support for migrants fleeing violence and extreme poverty in the Northern Triangle (Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador).

In the summer of 2018, HIP took leadership of the Central America and Mexico Migration Alliance (CAMMINA), a former donor collaborative that has granted $15 million to nonprofits addressing migration issues.

CAMMINA is now a HIP program that seeks to address the root causes of forced migration throughout Central America and support the nonprofits addressing migrant needs.

Last summer, HIP also initiated a rapid response campaign to the family separation crisis unfolding in the U.S., establishing a Family Unity Fund to support the short- and long-term needs of affected children and families.

Currently, HIP is mobilizing a funders’ working group with foundation partners interested in supporting the millions of Venezuelans who have fled the country.

There is much the philanthropic community can do to support organizations and efforts that seek to address the Venezuelan refugee crisis.

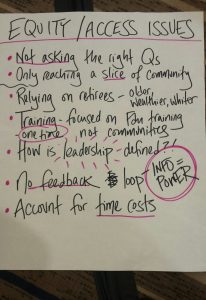

NCRP’s Movement Investment Project has made some useful, evidence-based recommendations for advancing the pro-immigrant movement:

- In order to adequately respond to the fast-moving crisis, foundations should move away from the traditional grantmaking process and adapt quicker, more agile giving.

- Provide multi-year, general operating support that can be used flexibly by organizations responding to shifting conditions on the front lines.

- Refocus philanthropic giving to influence state and local immigrant policymaking, where victories are easier, instead of funding efforts to change federal policy.

- Support the creation of livable salaries and health benefits for those working on the front lines, where burnout is a common side effect of the constant crisis response.

From the political to the personal

While I haven’t been back to Venezuela for 14 years, as an immigration and refugee lawyer, I have helped other Venezuelans resettle in the U.S.

And like many of my clients, I cannot go back. It’s not safe. With almost no state or police protection, kidnappings and violence occur with impunity.

Of course, I’m terribly worried about my family and friends still living in Venezuela. I try not to imagine how much worse it can still get. I’m heartbroken about what has happened to my country.

I look forward to a time, soon to come, when Venezuela can rebuild and its people can live in safety and health. Until then, I will continue to advocate for those still living in Venezuela and for the millions who have left and are still struggling to survive.

I know that the global philanthropic community can make a tremendous impact on their lives by supporting the organizations that are working on the front lines to help. I live in hope for those better days.

Amalia Brindis Delgado, Esq., is director of programs and strategy at Hispanics in Philanthropy. If you’re interested in partnering with HIP to respond to the crisis of migrants fleeing Venezuela, please reach out to her at amalia@hiponline.org. You can also join their upcoming HIPGive.org crowdfunding and giving circle campaigns to support organizations leading the response for Venezuelan migrants! Follow the link to get updates.

Photo by Policía Nacional de los colombianos. Used under Creative Commons license.

1. For the purposes of this article, the philanthropic responses includes documented aid from governments and international institutions. Collective private philanthropic funding has not been confirmed yet.