“Truth is ever to be found in simplicity, and not in the multiplicity and confusion of things.”

– Sir Isaac Newton

Sometimes it is helpful for a genius to remind you what is important, especially one who discovered most of the laws that govern the operation of the natural world and, ultimately, our lives.

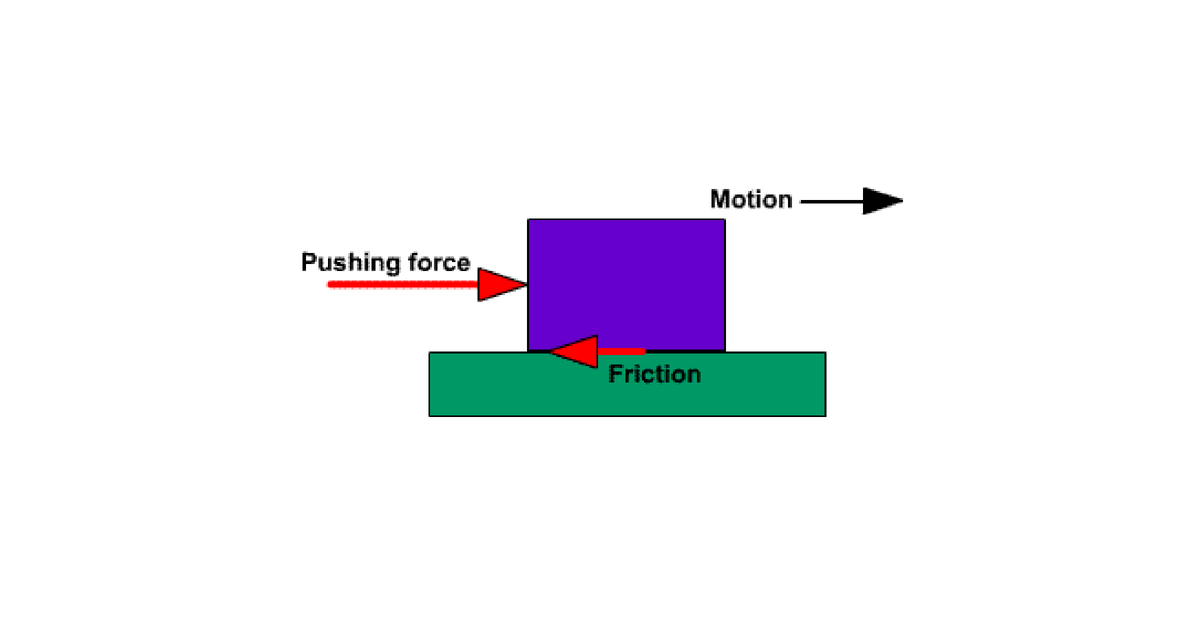

Sir Isaac Newton defined the laws of motion and the forces, such as friction, that shape the way we move and act. And these same insights can inform how we can transform the practice of philanthropy for the better by eliminating some of the “friction” that takes us away from the truth of simplicity.

We bring the perspectives of a philanthropist and a grantseeker to this issue, united in the belief that the size and urgency of the challenges facing us today require that we accelerate the progress of the social sector and how it is funded and supported.

4 Sources of “friction” in philanthropy

Let’s start by asking a deceptively simple question: What are the major sticking points in the practice of philanthropy where we feel the strongest sparks of friction?

1. The DANCE of Donor Cultivation and Prospecting

Social change is a relationship-based business that aims to solve global, systemic problems. This structure creates a fundamental mismatch between the sources of funds and the customers who use these funds to deliver programs, services and products; conduct research or undertake advocacy.

While these uses often operate on market principles, requiring consistency of access to and use of capital to achieve goals, most sources of funds have few accountability mechanisms besides a payout percentage and general board oversight, which means capital can be delivered in ways that are lumpy, unpredictable or unexpected.

This mismatch has major consequences on how grantseekers find, research, cultivate and engage donors.

2. The MAZE of Grant Applications

Once the grantee has scaled the barriers to entry, the real complexity sets in.

While most philanthropies have moved to online systems, there is little if any alignment across foundations or donors in the design of their applications or the details they request with respect to budgets, metrics or more text-based content.

While these online systems bring increased security and consistency, they also create boxes into which organizational and financial needs must fit. The lack of standardization across the field inevitably creates the Babel of Grant Reporting (see below) because unique inputs drive unique outputs and, even more importantly, unique impacts and change.

3. The BABEL of Grant Reporting

Few topics in philanthropy have taken up more print space than this one, especially given our sector’s love affair with data and metrics. Of course, meaningful impact data usually requires research rigor, which comes at a price rarely affordable by the nonprofit grantee or fully funded by the donor. While we all know that “we are what we measure,” we also know that measuring too much to satisfy each funder reveals little of value.

4. The ANXIETY of Grant Timing, Renewals and Exits

After doing the Dance, navigating the Maze and interpreting the Babel, the grantee too often faces gulps of anxiety rather than the pleasure of a successful sale.

When will the grant arrive? Can we renew, at the same level, and shortcut some or all the steps along the route next year? If not, when will we know, and will you do anything to help us make this transition to new funding?

Again, the fundamental mismatch between the imperatives of the social sector and the practices of philanthropy too often make a victory feel short-lived and as a result, leave less room for partnership between grantseekers and grant providers.

4 Ways to practice “frictionless” philanthropy

How are today’s philanthropists, and their partners, adapting their practices in pursuit of more “frictionless” philanthropy that could inspire the 21st century Isaac Newton to discover a new natural law? Here are 4 examples from the Emerson Collective that have shown initial success:

1. Deliver capacity-building services like an employee benefit.

Identify and provide a range of services that strengthen organizational skills and capacities similar to how employers deliver employee benefits.

Grantees elect to buy a service and submit a receipt to be reimbursed – no grant required! They also submit a brief report (maybe even a few bullet points or sentences) on why it mattered or worked, or didn’t, to determine if it should be offered again.

2. Offer small grants to test new methods of approval and reporting.

Experiment with simple, online methods of allocating small grants that reduce time spent, paperwork submitted and reporting required.

Ask grantees to present the “investment case” while also describing how the funding aligns with their priorities, as well as the priorities of the philanthropy.

A small grant program offers a laboratory to explore what “frictionless” grantmaking might look like in areas where the philanthropist knows less about the grantee, or less about the area in which the grant is being invested.

3. Formalize exit grants in ways that give grantees a sense of control.

Be transparent about grant cycles from the start, and communicate clearly with grantees throughout the relationship.

Jointly craft funding strategies that allow the grantee to plan for the transition and, when possible, fill the funding gap, leveraging access to consulting services or training that could help with the task.

4. Use technology and convening to share knowledge, create learning communities and simplify reporting.

A foundation and/or donor has convening capacity and technological resources that can be used to educate, network, advocate and inform.

These resources can build networks of grantees that can support each other or connect grantees to external resources that they could never afford themselves.

Convening builds networks and power and allows sharing of knowledge and insights. Strong technology support can supplement nonprofit capacity in ways that enhance their work and visibility – creating benefits for all.

Newton did not have the benefit of technology to aid in his discoveries. While he might have lived in a simpler world, it still provided him with ample examples of how people make things too complex and confused.

What are other practices for grantmakers towards a more “frictionless” philanthropy? Share your ideas in comments below or tweet using #FrictionlessPhilanthropy.

Anne Marie Burgoyne is managing director, social innovation, at Emerson Collective, and Andrea Levere is president of Prosperity Now. Follow @AMInnovation @EmCollective, @alevere, @ProsperityNow and @NCRP on Twitter. To learn more, read Levere’s recent Responsive Philanthropy article, “Learning from Emerson Collective’s ‘philanthropic recipe’ for these times.”