Editor’s Note: Aaron Dorfman, executive director of the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy and a graduate of the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy at Indiana University, gave the commencement address there on May 10, 2015. What follows is the text of his address, as prepared for delivery.

Good afternoon. It is a great honor to be with you all today as you begin exciting new chapters in your lives. I had so much fun reading the descriptions of this year’s graduates. You are an impressive and accomplished group, and I know you’re going to do amazing things.

I’m going to share today a little about my story, my journey into philanthropy. Then I’ll offer up one overarching theme and three specific suggestions for how you can make a difference in the world with a career in philanthropy.

Like many of you, I’m sure, I was lucky enough to be born into a family that was especially committed to loving our fellow human beings, with all of their beauty and all of their flaws.

My grandparents were all immigrants to this country, trying to make better lives for themselves and their children.

My grandfather on my father’s side, Isaiah Dorfman, had a special concern for working class Americans, as did many Jewish immigrants. And his love for working people led him to take action to help ensure workers were not exploited. As a young attorney, my grandfather helped write the Wagner Act, which, as you probably know, gave organized labor the right to bargain collectively.

My mother, Carrie Dorfman – and happy Mother’s Day to all the moms out there – was one of the first women ordained as a minister in the Presbyterian Church. She served as the chaplain at the women’s prison in Shakopee, Minnesota, and she had a special love for women who had been abused, exploited, left out and forgotten.

My father, Tom Dorfman, was a junior high school teacher. He also founded the local chapter of Amnesty International and helped Native Americans in our community secure a place to build a sweat lodge.

For me, having a family so fully committed to loving humanity and working for justice helped prepare me for a career in philanthropy. And as I look out at you all today, it’s clear that many of you also have enjoyed family support for this important work ahead.

I did my undergraduate work in political science at Carleton College in Minnesota, where the late Senator Paul Wellstone was my mentor. For those who don’t know about Paul, he was the Elizabeth Warren of the U.S. Senate from 1990 to 2002, an outspoken liberal populist who championed the underdog. Before he was a senator, however, he was a college professor. And he’s the primary reason I got started with a career in philanthropy.

One day during class my sophomore year, Professor Wellstone began asking students what they intended to do after graduation. When he got to me, I said I would probably become a teacher, like my father, but that I wanted to teach in an inner city school where I could really make a difference.

Paul ripped into me in front of all my peers. “Aaron,” he said. “If you really want to make a difference for those kids, you’ll become a community organizer.” He said that if I was serious about everything I’d been saying in class for the past nine weeks about justice and fairness, that working to change the systems that keep people poor and powerless was the only choice.

Well, I didn’t know that a person could work full time as a community organizer, but it turns out you can. And that’s what I did. For 15 years, I worked with low-income folks, helping them build power and win improvements on housing, education, public safety, transportation and more. I was on the grant seeking side of the philanthropic sector, doing important work with helpful funding from a diverse set of grantmakers.

Then, fourteen years ago, in 2001, while I was still working full time, I made a decision that led to an exciting new chapter in my life – I enrolled in the executive master’s degree program at what was then called the Center on Philanthropy, and what is now, of course, the Lilly Family School of Philanthropy at Indiana University.

As a community organizer for a small-budget operation, I didn’t make much money, and so the tuition scholarship discount the Center offered was tremendously helpful. I continued pursuing the degree, a few courses at a time, over several years. I didn’t think I was ever going to leave community organizing, I just wanted to learn and know more about philanthropy. I wanted to get inside the heads of the donors and the foundation program officers, in the hopes of being able to raise more money for the social justice work I was so passionate about.

But then, in the fall of 2006, I got a call from a recruiter for the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy and was hired as NCRP’s executive director in early 2007. I began a whole new journey working to improve and transform how philanthropy is practiced, and the education I received here at Indiana was absolutely essential in preparing me for my current role.

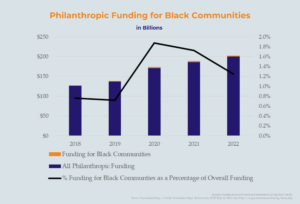

As you all know, foundations give out more than 50 billion dollars every year, and total charitable giving is over 300 billion dollars annually.

The fact is, where the money goes, and how it’s given away, matters. It matters a lot. I spend my days now working on research and advocacy to help our nation’s grantmaking foundations be more responsive to those with the least wealth and opportunity.

How much are we investing in the opera, as compared with Afro-Caribbean dance or other community-based arts programs? Are we giving too much to Harvard and not enough to the nation’s community colleges? Are we providing enough general operating support, or are we needlessly restricting our funding? Are we funding food pantries when we should really be investing in advocacy to expand government support for food stamps and school lunches? These are the kinds of questions I spend my days trying to get our sector to wrestle with.

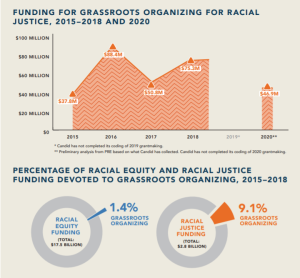

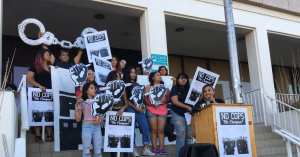

Philanthropy has accomplished many great things, but it’s clear to me – and I hope to you, too – that we can do so much more. Less than 9 percent of foundation grant dollars, for example, are intentionally benefitting communities of color. Given the great challenges our communities face – police brutality, mass-incarceration, entrenched poverty and more – shouldn’t we be doing better?

Good philanthropy, real philanthropy, is all about loving humanity. If you want to make a difference with a career in philanthropy, you’ve got to keep that love for humanity front and center in your work, all the time. Without that, nothing else matters.

The kind of love I’m talking about is not sappy or sentimental. Princeton Professor Cornel West said, “Never forget that justice is what love looks like in public.”

Theologian Carter Heyward wrote in her great work Our Passion for Justice: “Love is not fundamentally a sweet feeling … As advocates and activists for justice know, loving involves struggle, resistance, risk.”

The fact is that making an impact with a career in philanthropy means you’re going to have to struggle and take some risks. You can’t make an impact if you’re comfortable all the time.

So that’s my overarching piece of advice – keep love for humanity at the center of your work.

There are three additional, slightly more concrete, suggestions I want to offer as you embark on and continue your careers in philanthropy:

1. Always remember it’s not your money.

When we work in the philanthropic sector, whether as grant makers or grant seekers, donor or doers, we have to remember that we are stewards. The dollars entrusted to us are not our own. We have been given an imperative responsibility to help ensure those dollars do the most good in the world. Even if you’re the donor, once you give the money to a foundation, it’s not your money anymore – it’s money for a charitable purpose. What’s more, tax policy in the United States means that every time a donor makes a gift, assuming he or she claims a deduction, other taxpayers are also subsidizing that gift. Charitable dollars are therefore partially public dollars. If we remember that, it’s easier to feel accountable for making good use of the funds that have been entrusted to us.

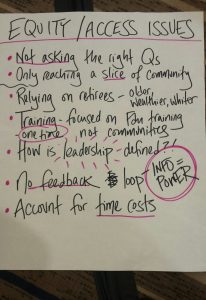

2. Listen to and share power with people who are directly affected.

Too often in philanthropy, we listen to the experts, to the “smart” people who have all the right credentials. But more than two decades of experience shows me that you’ve got to listen as much or more to the people who are directly affected by the issues you’re working to address as you do to the so-called experts if you want to make a difference for the long term. And don’t just listen to them. Share your power. Put them on the board of directors if you’re in a position to do that. If you’re spending all your time with technocrats and powerful elites, you’re doing it wrong. When we democratize philanthropy, we unleash its true power.

3. Take risks, be bold, and stand up for those who are oppressed.

What philanthropy needs, more than anything else, is people with heart willing to take a stand. Some people talk about neutrality or objectivity as one of philanthropy’s assets, but I think that’s just not true. Neutrality benefits the status quo. People with power and privilege want you to be neutral. One of my favorite quotes on this is from Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who said, “If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor. If an elephant has its foot on the tail of a mouse and you say that you are neutral, the mouse will not appreciate your neutrality.” If you want to make a difference with a career in philanthropy, you’ve got to stand for something. And if you’re on the giving side of the philanthropic table, you’ve got to support the rabble-rousers, the community organizers and the advocates who are fighting the good fight. Moving money to those kinds of people and organizations has a tremendous bang for the buck. It’s true, we’ve done the research.

My friend Senator Wellstone used to say that he went to Washington to speak up for the little fellers, not the Rockefellers, because the Rockefellers already had plenty of people speaking for them. Philanthropy, too, already has plenty of people speaking up for the Rockefellers. We desperately need people who will speak up for the little fellers.

And so I’ll close with a wish. My wish for you is that at some point in your career, you’ll get in trouble for standing up a little too boldly for the downtrodden in your communities. Then you’ll know you’re really making a difference with a career in philanthropy.

Thank you, and congratulations!

Aaron Dorfman is executive director of the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy. Follow @NCRP on Twitter.