As someone with longtime philanthropic interests in the South, I want to recognize the singular achievement of the As the South Grows series.

Nothing in recent memory has as accurately captured the voices of local southerners – from Appalachia to the Lowcountry – whose work is driven by a commitment to real change for some of the least represented people in the country.

Those of us who support and promote rural philanthropy often ask folks, “Have you read the As the South Grows series? If not, you need to!”

But there is a missing piece of the philanthropic story: Health care conversion foundations, also called health care legacy funders, are often the dominant funders in the South.

These funders, born of the sale of non-profit healthcare organizations (e.g. hospitals, insurance companies, physician groups) to primarily for-profit health care groups, are often outsized funders obligated to serve rural communities.

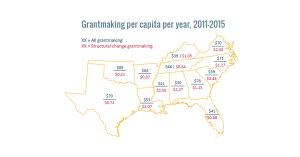

A 2015 report from Grantmakers in Health (GIH) showed at least 75 conversion foundations in the South with assets of more than $8 billion. These numbers continue to grow, with another 20 foundations likely to come online in the South since the GIH report data was collected.

The recently announced pending sale of the nonprofit Mission Healthcare in Asheville, North Carolina, to private healthcare company Hospital Corporation of America will create a new foundation serving 18 rural and very rural North Carolina counties with assets predicted to be upwards of $1.5 billion.

With a service area that contains less than a million people, this healthcare conversion will create perhaps the largest foundation in the country on a per capita basis – and one that will serve some very poor Appalachian counties.

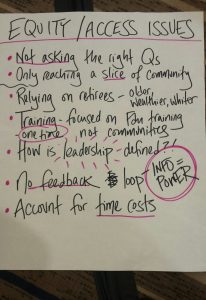

So, with all the financial mass and promise of healthcare conversion foundations, why are they not more prominently featured in As the South Grows? How do their investments reflect the focus on grassroots advocacy, poverty and structural change that As the South Grows describes and promotes?

The answer is: They don’t. At least, not as a whole.

There are notable exceptions in the region, including Danville Regional Foundation (Danville, Virginia), the Mary Black Foundation (Spartanburg, South Carolina), Allegany Franciscan Ministries (Palm Harbor, Florida), The Greater Clark Foundation (Winchester, Kentucky) and others.

However, the bulk of conversion foundations in the South are punching well below their weight class when it comes to funding structural change.

Like too many of their peers across the philanthropic spectrum, they hesitate to invest deeply in the kind of on-the-ground advocacy, difficult conversations and paradigm shifts that are necessary to dismantle systems and structures that perpetuate inequity and poverty in the region.

The reasons for their hesitancy aren’t mysterious. Some are still dedicated exclusively to supporting health care services for the poor, per their origins and regulatory environments.

Many have moved to a social determinants of health frame, which looks upstream from health care to the causes of poor health outcomes, such as poverty, education quality, poor nutrition, homelessness and many other social factors. These funders invest in early childhood, food access, built environments and more to improve social conditions.

Support for local advocacy and grassroots system-led change is a natural extension of social determinants work. Unfortunately, too many health conversion funders are content to bide by only the old tried-and-true mechanisms of philanthropy, making passive grants to traditional nonprofits that only respond to the effects of social determinants rather than addressing the causes.

The other barriers that hold Southern conversion foundations back from making a positive dent in the South’s current systems and structures are the same as for philanthropy in general: lack of experience; no peer group to lean on; an aversion to risk taking; and the inability to readily measure the value of investments in advocacy.

(The cynical might add that many of Southern conversion foundations are led by board and staff who represent the same traditional leadership that has nurtured and reinforced historic power structures. While that may be true in some cases, I don’t believe that’s representative of the majority.)

What will create a change? Conversation. I encourage other Southern-based funders that have successfully moved beyond these roadblocks to intentionally pursue conversations with conversion foundations.

Show them your good work; engage in board-member-to-board-member conversation; train them on how to measure advocacy success and vet grassroots grantees.

Staff at successful foundations should go to conferences and meetings, and share the tactical ways that conversions funders can dip their toes in the grassroots advocacy funding pool.

And every grantmaker association in the region should provide at least one annual training on the mechanics of making good grassroots advocacy grants.

Most importantly, philanthropic work on social determinants of health and underlying systems change in our region must be based in the Southern experience and the unique history of conversion foundations.

While NCRP and others have rightly decried the lack of investment in the South by national funders, this is a battle that is only going to be won by leadership from within our own ranks.

The world of Southern conversion foundations is only just hitting its stride. Support for advocacy and grassroots systems change is the obvious next step.

Allen Smart spent more than two decades in leadership roles with rural funders in the Southeastern U.S. before launching RuralwoRx, a national consultancy aimed at increasing and improving rural philanthropy across the country. Follow @NCRP and #AstheSouthGrows on Twitter.

Leave a Reply