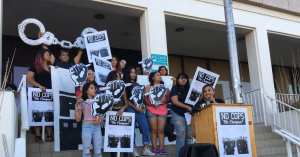

When the City of Atlanta proposed an 85-acre spot within the Weelaunee South River Forest in Dekalb County, Georgia as the site of a new “public safety” training facility, the backlash was swift. There were questions about what the training facility would be used for, including militarized training, concerns over unnecessary deforestation, and what it meant to build a police training facility in a predominantly Black community. As protests escalated, in January 2023, forest protector Manuel Esteban Paez Terán (also known as Tortuguita or “Little Turtle”), was executed by police adding fuel to an already very hot fire.

Despite these concerns and avoidable tragedy, construction on Cop City began in the spring of 2023.

How much more extraction must Black, Indigenous, and other People of Color endure before there are no more spaces left to live in peace? Cop City is but one example of sacrifice zone. It is important to recognize that the forest is not just a place for recreation, but also an important indicator of a thriving, healthy community.

In the South River area of Atlanta where the training facility is being built, “71-88% of the population is Black, with asthma rates in the 94th percentile and diabetes in the 80th percentile nationally.” Furthermore, most residents in these zip codes live below the federal poverty line. Removal of the forested land only to be replaced by a military-style training facility complete with shooting ranges and 24/7 police surveillance means removal of one more sanctuary for populations already pushed to the margins through economic exclusion and over policing. What does it mean when a source of refuge for so many becomes a source of fear and hypervigilance? How does further militarization bring about clean air, safe drinking water, bountiful outdoor space, and affordable housing? How does increased policing support thriving connected communities with abundant food security? How do the environmental impacts of Cop City consequentially affect the reproductive freedoms of communities in Atlanta as well?

Sacrifice Zones for Marginalized

The concept of these sacrifice zones immediately challenges one of the key pillars of the reproductive justice framework, the right to parent children in safe communities. In the long term, it threatens to disrupt the remaining pillars of upholding the rights to have children, to not have children, and bodily autonomy.

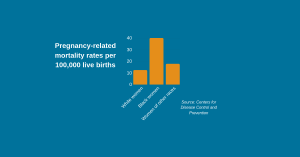

When communities of Black, Indigenous and other People of Color are surrounded by pollution and environmental hazards, the risk of many existing reproductive consequences extends from miscarriages, maternal mortality, birth defects, and infant deaths.

The increase in police and surveillance in the area will also directly impact those seeking abortion services in a region that is historically committed to using the power of the state to criminalize limits on bodily autonomy, including abortion care. This can also look like organizers and activists being charged with racketeering for pushing back against the construction of Cop City, abortion organizers, and practical support providers especially considering that they rely so heavily on tactics named in the initial Stop Cop City indictment. Of these arrestees, gender non-confirming activists will face harsher police violence.

Those parenting their children will be raising their families in overpoliced communities while living in the constant fear that the state will take their children from them across systems of policing from child protective services to prisons, or state violence at the hands of police resulting in the deaths of their children.

We must remember that those on the frontlines of these kinds of projects are also those living on the frontlines of climate and reproductive injustice. The deforestation of hundreds of acres for the purpose of further scrutinizing Black, Indigenous and People of Color communities and families for existing is alarming within itself.

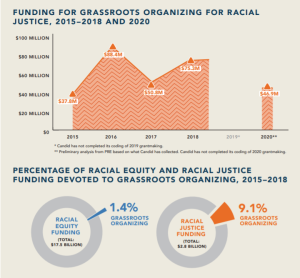

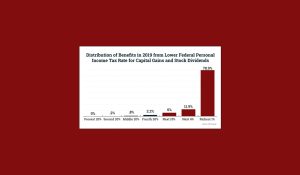

In June 2023 $30 million in city funding was approved for the project, which now has a total budget of $111 million. The primary source of the funding comes from the Atlanta Police Foundation, which has several corporate sponsors, donors, and foundation-based funding including AT&T, Waffle House, and the Robert W. Woodruff Foundation. This brings up a larger issue, should philanthropy really be funding policing?

Fund Frontline Communities Not Cops

As we look toward philanthropy to be more responsive and shift significantly more resources to the frontlines, what does it mean for funders to continue to support and uphold systems of police violence and militarization at the expense of those communities? Putting funding behind such projects only increases the dominant power vacuum that is the police-industrial complex.

Police departments do not need more funding. Community members surrounding the forest need more funding for their healthcare needs, especially as they continue to deal with polluted air, water and soil. Organizers and activists fighting racketeering charges need more funding for bail funds and legal representation.

Abortion funds and independent abortion clinics that will continue to serve abortion seekers in the state of Georgia need more funding as access to care is further criminalized and surveilled. There are many groups that are fighting this intersectional issue and that are in dire need of funding as this fight continues:

- ATL Solidarity Fund

- Community Movement Builders

- American Friends Service Committee

- Forest Justice Defense Fund

- NAACP Legal Defense Fund

The fight to Stop Cop City is not a singular issue; the building of Cop City has an impact across margins and movements. The construction of this dangerous military facility knows no borders or margins and seeks to harm Black, Indigenous and People of Color communities for years to come. Philanthropy has a responsibility to repair the harm done to these communities, not exacerbate it.

For Further Reading:

- Cop City and the Escalating War on Environmental Defenders (Sen, Colchete 2023)

- Atlanta’s ‘Cop City’ and the relationship between place, policing, and climate (Love, Donoghoe 2023)

- Military equipment flowing to local law enforcement raises questions (Cook, 2013)

- Environmental impact targeted in new push against ‘Cop City’ (Alcorn, 2023)

- Atlanta community members warn of environmental damage from ‘Cop City’ (Uyeda, 2022)

- Environmental pollution lawsuit may pump the breaks on Cop City construction (James, 2023)

- Anger, Protests, and Vandalism Break Out Over Philanthropy’s Support of the Police (Rendon, 2024)

- Activists Lock Themselves to Construction Equipment to Protest “Cop City” (Garrison, 2024)

- Atlanta wants to build a massive police training facility in a forest. Neighbors are fighting to stop it (Maxouris et al, 2022)

- The Companies and Foundations behind Cop City (American Friends Service Committee, 2023)

- The Green to Blue Pipeline: Defense Contractors and the Police Industrial Complex (Rahall 2015)

- Police Shot Atlanta Cop City Protester 57 Times, Autopsy Finds (Lennard 2023)

- This is the Atlanta Way: A Primer on Cop City (Herskind 2023)

__________________________________________________________________________________________________

Brandi Collins-Calhoun is a Movement Engagement Manager for Reproductive Justice and Gender Violence at the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP). A writer, educator and reproductive justice organizer, she leads the organization’s Reproductive Access and Gendered Violence portfolio of work.

Senowa Mize-Fox is a climate justice organizer and activist and the Movement Engagement Manager for Climate Justice and Just Transition at NCRP.

Leave a Reply