Any Southern organizer knows the feeling of being assessed by funding criteria developed in the sterile conditions of a foundation boardroom.

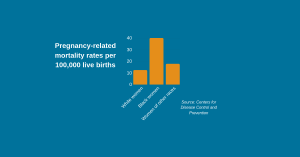

It’s not unlike the feeling of being in the cramped quarters of a doctor’s office, assessing what you can and can’t disclose as a provider runs through a list of questions that have little to do with who you truly are and what’s going on with your body.

This clinical diagnostic process manages to be invasive and alienating; so too does grantmaking that misses the mark.

But I’ve also experienced the opposite. My family gets care from a family practice doctor who breaks script enough to create a human connection, addresses the additional stresses that a queer Southern family shoulders and treats each of us as whole people.

I’ve seen the same with some funders who, in both word and deed, approach the South – and the lives of Southerners – with care, commitment and grantmaking practices that speak to the distinct features of our region.

The difference isn’t just a palpable shift in how interactions feel; it actually makes for better outcomes.

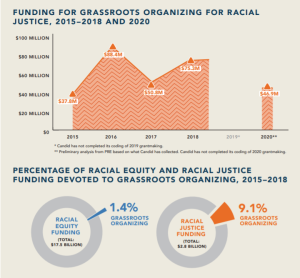

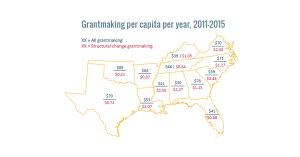

As the South Grows: So Grows the Nation, a new report from National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy and Grantmakers for Southern Progress, interrogates an idea I’ve heard countless Southern organizers and strategists obsess over: Imagine what would be possible if funding was done differently in the South.

Above all, what I hear in this report is an invitation for funders to become new kinds of practitioners: More vessel, less gatekeeper; more situational, less linear; more relational, less transactional.

And with this, to let go of the power that comes with money and trust that the world will be better for it.

In the South, there is nothing abstract about the times we are living through. The forces of white supremacy and Christian nationalism are exerting themselves at every level of Southern politics. Our state legislatures are labs to test draconian policies (like Mississippi’s HB 1523, the nation’s most extreme anti-LGBTQ law) that are then introduced at the federal level.

As always in the South, many things are true at once: Resistance is also alive and well here. Across the region, you see incredible examples of creative, innovative programming and intersectional rapid response organizing.

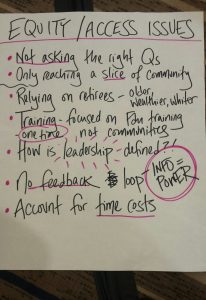

The report takes a deep dive on models of funding that work in the South, including engaging history, race, gender and class in grantmaking practices.

In this spirit, I want to lift up four practices I’ve experienced from funding practitioners that have been gamechangers in our work with them:

1. Stay curious. Ask questions like:

- What does your community need?

- What does your community dream of?

- Why did you approach this issue that way?

Questions like these invite people to speak more authentically about their communities and work rather than responding in the dialect of grantspeak. When we speak authentically about what matters to us, it’s a lot easier to get clear on what matters and to be honest about what’s working and not.

2. Figure out how to move money quickly.

In 2018, we are working on sending people to Mars and can isolate strands of the human genome, things we once thought impossible.

It is entirely possible to move money quickly. And it’s necessary if we are to respond adequately to the chaos and danger of this political moment.

Recently, a funder told me that they had money sitting in an account and the greenlight to disburse it, but couldn’t figure out how.

It became clear that the real issue was that this foundation wasn’t ready to trust organizers with rapid response funding.

3. Have faith. And if you don’t, be willing to ask why.

Listening to people on the ground, trusting their leadership and moving money so they can do the work: That’s trust-based grantmaking, but it’s also a spiritual practice rooted in relationship, a faith in the unseen and a readiness to move mountains to create the beloved community.

If you’re not there yet, what would it take for you to trust like this? Are there war stories about grant funds being misused? Of course, but there also are war stories about funders exploiting the work of grantees.

We either get stuck in these old patterns and stories or create new ones.

4. Build space for revision into grantmaking and reporting practices.

Will some of our projects fail in their initial inception? Definitely. Every work of significance – innovations in medical treatment, breakthroughs in impact litigation – emerged from a long trail of iterations, failed attempts and revisions.

Be a thought partner as we learn, offer specific feedback, share other models with us and build reporting documents that ask us to learn and revise rather than spin stories of unbridled success.

Consider multi-year funding that includes time and space for reflection and revision, rather than one-year project specific grants that operate on a binary model of success and failure.

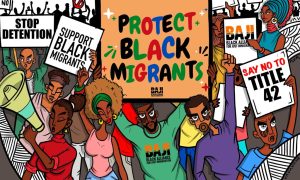

The recommendations in So Grows the Nation echo what I hear from the most interesting voices in other sectors these days. At the border, attorneys are practicing “community lawyering” to represent parents and children who have been separated. Clergy stepped down from the pulpit to act as “movement chaplains” in Charlottesville, Virginia, last year.

Perhaps this is part of how we will build the world anew: By casting aside the old vocational habits that entrench us in broken systems of power and control and instead honing the skills that 21st century America requires of us.

Rev. Jasmine Beach-Ferrara is a minister in the United Church of Christ and the executive director of the Campaign for Southern Equality, a non-profit that works for full LGBTQ equality – both legal and lived – across the South. Follow @jbeachferrara and @SouthernEqual on Twitter.

Leave a Reply