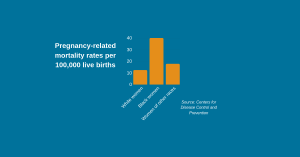

There’s a name for what happened to me when I tried to breastfeed my daughter, and I didn’t learn it until she was almost in middle school. It’s called DME-R, or Dysphoric Milk Ejection Reflex, and it’s a condition where a rush of intense negative emotions is released while nursing. This isn’t about willpower or not trying hard enough. It’s a biological process that can be impacted by stress, hormonal imbalance, trauma, lack of support, medical complications, and racism in the medical system. And like most things in reproductive care, Black and brown birthing people are more likely to suffer from it silently, misdiagnosed, and unsupported.

I’m speaking directly from that silence.

When I became a mother at 15, I did so with the weight of every stereotype sitting on my shoulders. I was young, I was Black, and I was determined to prove everybody wrong. In my family, breastfeeding wasn’t just encouraged, it was expected. “Breast is best” was more than a phrase; it was a tradition, a badge of honor, a rite of passage. So, when my body would respond to my daughter latching by crying, shaking and throwing up, no matter how hard I tried; when my breasts remained heavy but dry, my baby unsatisfied; it felt like more than a medical issue. It felt like a spiritual and cultural failure.

I didn’t know about DME-R back then. No one around me did. There was no lactation consultant in my hospital room. No one paused to ask about the full context of my labor or postpartum care. I was handed formula samples like a consolation prize and sent home without answers. And even more than the physical pain, it was the emotional toll that stuck with me. I cried, pumped around the clock, prayed. With each feeding, my body would quickly become violently ill. And with each feeding, I felt shame harden into self-blame.

As a teen mom, the world already assumed I would fail. And this? It felt like proof. I was the only person in my family who “couldn’t” breastfeed, and nobody could tell me why.

Years later, when I was working as a birth doula, I was sitting in conversation with a Black lactation consultant. I shared my story like I had so many times before, still holding that ache in my throat. She looked at me and gently said, “That sounds like DME-R.” In that moment, the truth cracked open.

I wasn’t broken. I had experienced something real, diagnosable, and common, especially among Black birthing people navigating systems not designed to listen to us.

That moment changed everything. I could finally grieve. Not just the loss of breastfeeding, but the loss of being held, seen, and properly cared for. I realized I had spent years carrying a wound that didn’t belong to me, it belonged to the broken systems that fail us over and over again.

This is why funding Black and brown lactation initiatives isn’t just important, it’s essential. We are still, to this day, dealing with a healthcare system that doesn’t listen to Black and brown bodies. Our lactation journeys are too often dismissed, under-researched, and unsupported. Young parents like I once was are still leaving hospitals with unanswered questions and deep feelings of failure, when what they really need is culturally grounded, community-rooted care.

Attending the Uplifting Black and Brown Lactation Success Conference at North Carolina A&T was a full-circle moment of healing for me. To be in a space curated by us, for us, where our stories were honored, not dismissed? That was powerful. I wasn’t just learning technical information, I was reclaiming my own story. I was finally in a room where DME-R wasn’t met with blank stares or brushed off with “You must not have tried hard enough.” It was met with care. With science. With ancestral wisdom. With solidarity.

This work is about healing, representation, and returning power to Black birthing communities. Janiya Mitnaul Williams, Director of North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University’s Human Lactation Pathway 2 Program human lactation program, beautifully articulates this in her 2021 blog, “Disrupting Disparities & Exclusion in Lactation.”

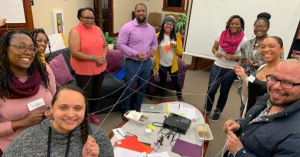

A few years ago, NCRP’s Reproductive Justice team held a retreat in Greensboro, NC and spent time at North Carolina A&T’s Human Lactation Pathway 2 Program, a Black-led, community-rooted certificate program housed in the Department of Family and Consumer Sciences. Designed to train lactation consultants who serve historically harmed communities, the program centers culturally grounded care and real-world communication skills.

NCRP’s Reproductive Justice Team sat in on lectures, spoke with students and faculty, and heard powerful stories. Many students had experienced trauma around lactation firsthand and wanted to offer the support they never received. Some came from public health, others from speech pathology, understanding how early feeding issues can shape everything from swallowing to speech development. The free lactation clinic programs now offer virtual and in-person support, embodying what it looks like when institutions are truly accountable to the people they serve.

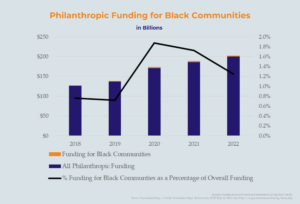

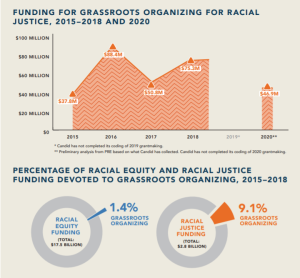

This kind of care isn’t a luxury. To call it that is a dangerous mistake that erases the labor and urgency driving Black and brown lactation justice work forward. Philanthropy has a responsibility here. Too often, “maternal health” funding goes toward top-down, one-size-fits-all solutions that never reach the people doing the real work on the ground. Meanwhile, Black and brown-led lactation initiatives are building networks of doulas, lactation consultants, peer counselors, and community educators, without the structural support they deserve.

We need sustained, intentional investment in:

- Black and brown-led lactation training programs

- Scholarships and certification pathways for community-based lactation workers

- Conferences like the one at NCA&T that create spaces for research, healing, and strategy

- Accessible, culturally relevant postpartum care in schools, clinics, and homes

- Resources specifically tailored to teen parents, queer parents, and low-income communities

Because had someone explained DME-R to me at 15, I could have shed the shame. I could have embraced my daughter’s infancy with more softness and confidence, knowing I wasn’t the only one, knowing it wasn’t my fault. That kind of care shouldn’t take years to arrive.

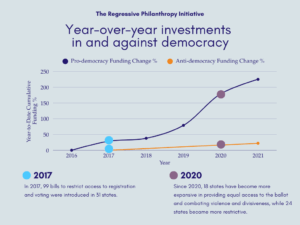

If you are in a position to fund this work, do it boldly. Do it without centering yourself. Do it by trusting the Black and brown lactation leaders who have been doing this work long before the dollars showed up. Listen to the birth workers, the aunties, the lactation scholars, the grassroots doulas, and yes, the teen parents who grew up and found their voice.

Fund the healing. Fund the truth-telling. Fund the spaces that allow us to reclaim our stories, our bodies, and our power.

And to every young Black and brown parent out there struggling to nurse or grieving the feeding journey they didn’t get to have, you didn’t fail. You were failed. We are fighting for you. And we’re not done.

Brandi Collins-Calhoun is the Movement Engagement Manager at the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP). A writer, educator and reproductive justice organizer, they lead the organization’s Reproductive Access and Gendered Violence portfolio of work.