In 2020, I remember being on a regional call with funders in New England who were optimistic that, after months of a global pandemic and a summer of the largest racial uprising this country has seen since the Civil Rights Movement, we were in a new era of philanthropy. I was not as convinced that those “unprecedented times” would lead to long-lasting change. Historically, philanthropy has always risen to big news moments like the 2016 election results, Supreme Court decisions, market crashes, and climate change disasters. However, as a whole, the sector’s old habits are tougher to break.

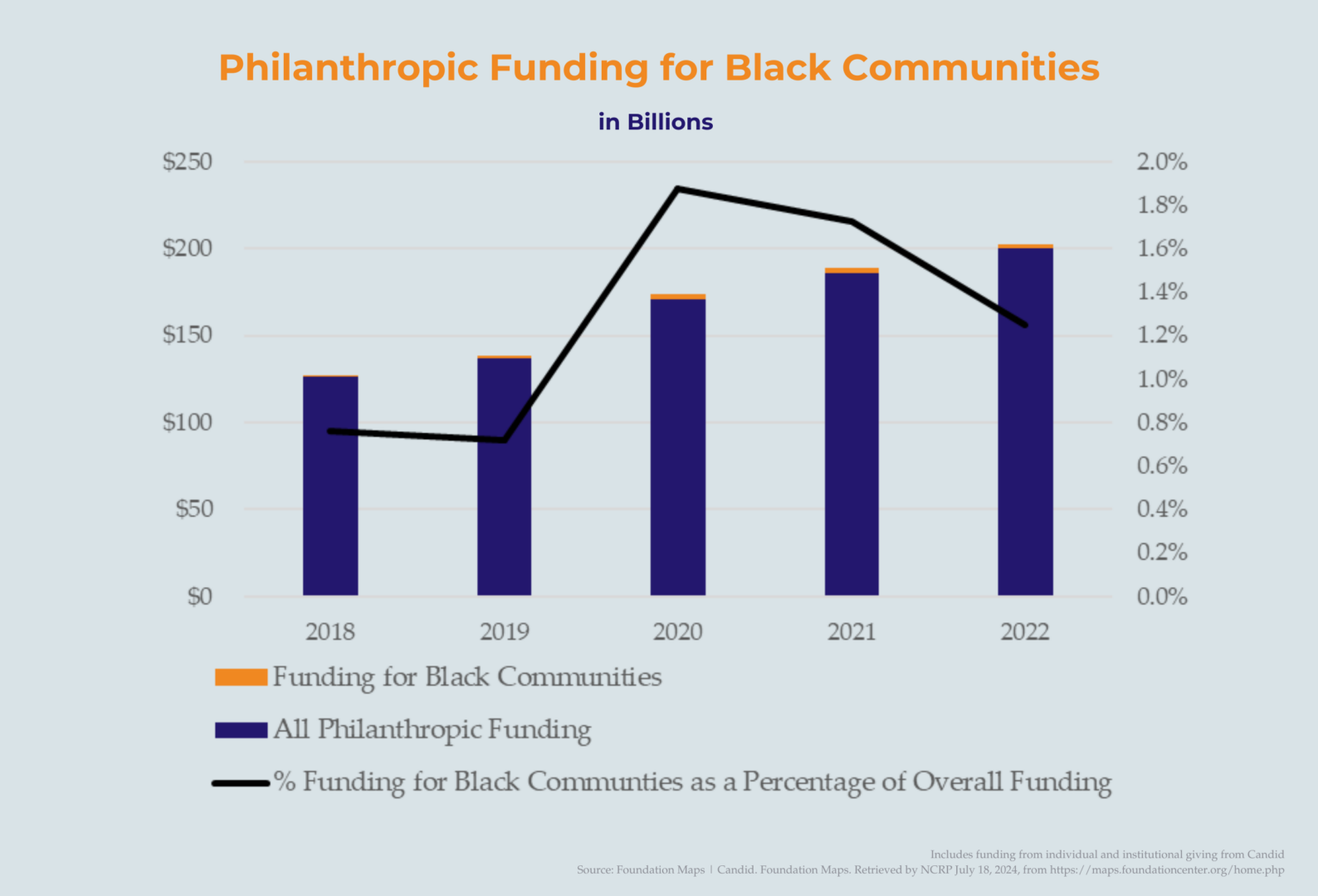

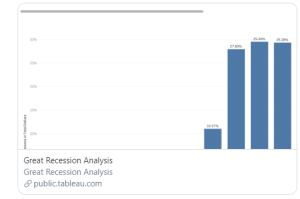

Since the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy’s 2020 report, Black Funding Denied, we have tracked multiple trends on giving to Black communities. In our latest published update, data showed a positive rise in funding in 2020 and early signs continuing into 2021. However, more recent 990 data shows that funding for Black communities is reverting to its mean.

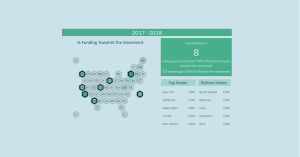

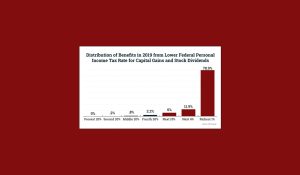

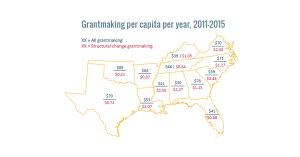

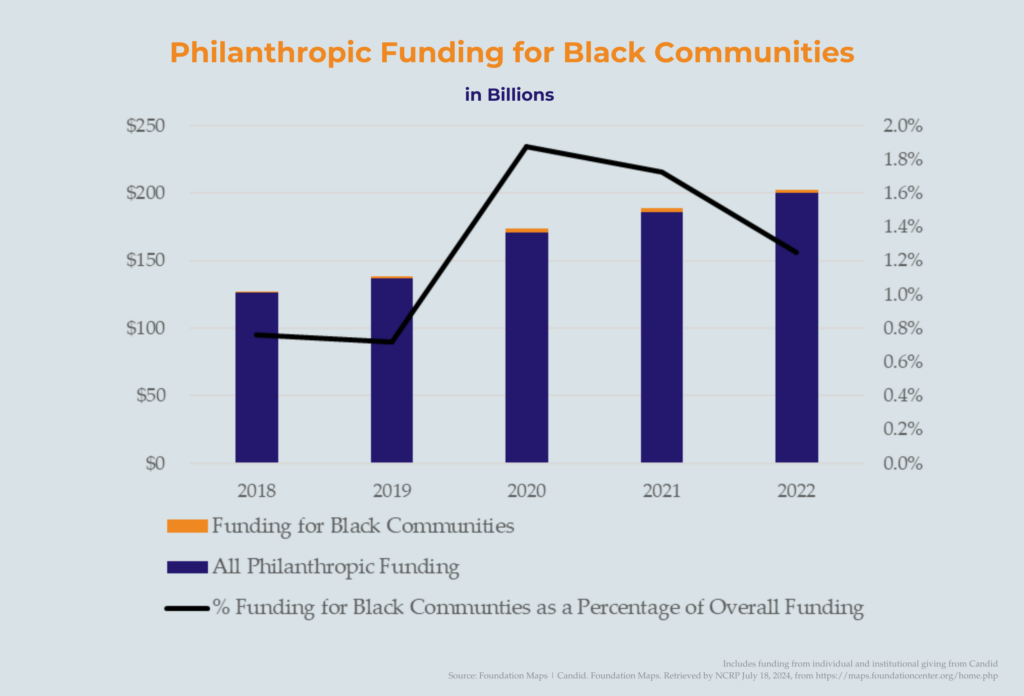

Funding for Black communities reached its peak at 1.9% of overall philanthropic giving in 2020 (still nowhere close to meeting the population share of Black people in this country). This percentage slightly decreased in the following years, dropping to 1.3% in 2022.1

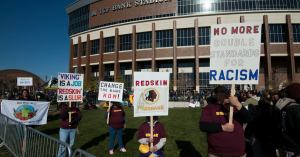

This drop off of funding to Black communities is troubling, but unsurprising. In my grants analysis experience, foundations do not commit more multi-year general operating support to marginalized communities in the same way when public pressure goes away. The outpour of support we saw in 2020 was directly driven by the pressure generated by Black-led social movements. So how do we turn reactive grantmaking for Black communities into sustained partnerships?

The data speaks for itself

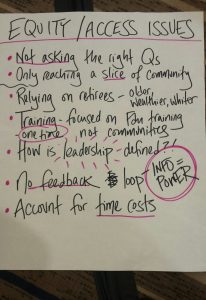

In reviewing ABFE’s recent Factsheets,“Key Facts About Nonprofits With Majority Black Leadership” and “Key Facts About Nonprofits With Black CEOs”, it struck me that Black leaders are consistently operating from a place of scarcity in comparison to their white counterparts. In their sample size, provided by Candid Demographic Data, 15% of CEOs identify as Black or African American. Yet, nonprofits with Black CEOs account for 28% of all organizations with budgets below $50,000.

The disparities only grow when you look at organizations with majority Black leadership –meaning a Black CEO and at least half the board identifies as Black. Two-thirds of majority-Black led nonprofits have budgets below $100,000 and only 2% have budgets above $10 million. Comparatively, at majority white-led nonprofits, only 21% have budgets below $100,000, and 8% have budgets above $10 million. Right now, funders are giving Black decision makers less to work with AND asking them to undo centuries of systemic racism in one to two years.

When NCRP published Black Funding Denied in 2020, our goal was to shine a light on the gross underfunding of Black communities by forcing foundations to reckon honestly with their role in these disparities. NCRP has always believed that a shift from one-time grants and initiatives to long-term, sustained investments in Black communities is an opportunity for grantmakers to embrace the values they, themselves, say they hold. But the motivation to change is not just in the name of equity.

Don’t wait for the next crisis

Targeted universalism, coined by john. a. powell, is the idea that “outgroups are moved from societal neglect to the center of societal care at the same time that more powerful or favored groups’ needs are addressed.” By supporting communities who have been historically and continuously ignored, we have an opportunity to create solutions that benefit everyone. We have seen this on a large scale with the Curb-Cut Effect and institutionally when internal policies reflect the unseen labor of Black women in particular.

My hope is that foundations don’t wait for another crisis to access their commitments, whatever their motivations may be. Philanthropy has the opportunity to disrupt existing sector standards. Funders must move beyond focusing on the next crisis, the next big idea, the next moment, and prioritize long-term sustainability. If the social good sector wants to win, we cannot keep up the same tired reactive patterns.

Research Manager for Special Projects and current Connecting Leaders Fellow at ABFE, Katherine Ponce engages in both qualitative and quantitative research projects to advance NCRP’s mission.

Before NCRP, Katherine’s passion to strengthen the involvement of community in philanthropy grew during her time at the Sillerman Center for the Advancement of Philanthropy. Here she analyzed data trends for the center’s publications and outreach to uplift field partners focused on participatory grantmaking.

Katherine earned a dual degree, an MBA in Social Impact and MS in Global Health Policy and Management, in 2021 from the Heller School at Brandeis University, and a BA in 2015 from Towson University.