Appeasement is in vogue. That doesn’t make it a good idea.

We’re barely a month past the 2024 election, and the hot takes are flying. But a clear theme is already emerging.

Former Hewlett program officer Daniel Stid captured it recently for the Chronicle of Philanthropy. In his op-ed, he calls on philanthropy to stop “funding the resistance” to Trumpism and instead “support pluralism in civil society.” The key to a healthy democracy, he argues, is to turn away from “the high-octane, all-or-nothing advocacy and activism” that have plagued the country since 2016 and are “further stoking the fires” of polarization.

Arguments like these misjudge the purpose of vital, community-led work and the movements that arise from it. They mistake centrism for pluralism, and they advocate neutrality at a time when speaking truth to power is necessary, not optional, for democracy.

It also won’t work as a strategy. An unapologetically brave, consistent, and vocal solidarity with social justice movements is the best thing funders can do now.

Here’s why.

Backlash by another name

Donor funding for equity and social justice movements has been wildly overstated. But some commentators insist that supporting these approaches at any level is counterproductive. These strategies are inherently polarizing, they argue, and that’s the reason our democratic norms are the mess they are today.

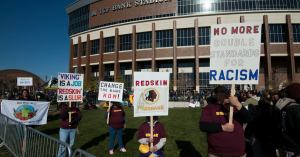

If this is the concern, let’s get specific. What exactly counts as polarizing? Is this what they fear will worsen the health of our democracy?

- Is it helping immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers access legal services, prevent family separation, and chart a path to citizenship?

- Is it making sure that queer people aren’t discriminated against in housing and in workplaces, and that trans people can live in joy without fear of state or personal violence?

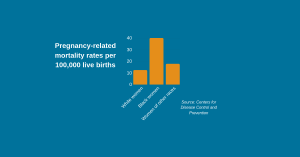

- Is vital healthcare like abortion access, doula support, and Black maternal health practices the issue?

- Are community-led fights for clean air, clean water, and a cooler climate the culprit?

- Perhaps reducing the racial and gender wealth gap or telling complete stories about our history is the problem?

For my money each of these examples, and many more like them, create a more truly pluralist world, not less. They all ensure that people too often kept from seats of power have a fair shot at correcting past imbalances and improving our collective norms, culture and policies. As a bonus, everyone tends to benefit from this approach too, in the same way that parents with strollers and workers with carts benefit from the curb-cuts that disabled activists spent years fighting for.

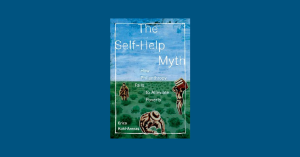

Yet even if these approaches are polarizing to some, isn’t that a strange metric for a worthy cause or good grant? Creating a better, more just world often makes enemies. Power concedes nothing without a demand, and demands aren’t made to make the powerful comfortable. Sixty years on from the March on Washington, it’s worth remembering that the civil rights movement of the mid-20th century was incredibly polarizing. It was also, to state the obvious, worth doing anyway – as are the fights for continued liberation today.

Human rights aren’t a popularity contest. We cannot change what’s possible by asking our dreams for a better world to sit down and whisper quietly in the corner. As James Baldwin wrote in 1962, “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

Nor can we pretend like these conversations are happening in an ahistorical vacuum. An entire ascendant far-right movement is actively pursuing a white ethnonational state with riches crowded even further at the top, bodily autonomy for the few, an overheating planet, and the criminalization of entire communities for just existing. And they’ve been abetted by patient, generous, flexible philanthropic dollars while the majority of donors sit quietly and neutrally on the same moving train.

Which begs the question: Who gets to decide when strategy A serves the lofty goals of pluralism, and when strategy B only fans the flames of division? Lately, it seems like “pluralism” has become little more than the new civility politics: a conveniently vague definition commentators can use to delegitimize overdue fights for justice and accountability as soon as they get impatient or uncomfortable.

I struggle to find the value in setting a civic table where open bigotry is begrudged for the bankrupt sake of moral “balance.” Without a clear moral backbone, an inconsistent standard like this is far more likely to indulge the loudest reactionary voices than reveal which work is worth funding.

Philanthropy’s still giving pennies for progress.

I’ve worked in the philanthropic sector for over a decade. I was around for the first Trump administration and most of the Obama administration before that. In all that time, have I seen philanthropy transform beyond recognition into a blazing beacon of progressivism? Hardly.

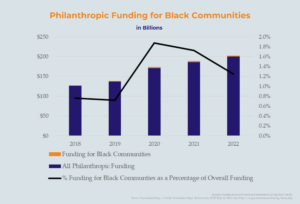

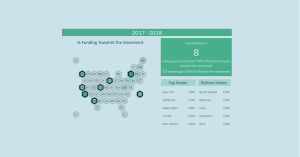

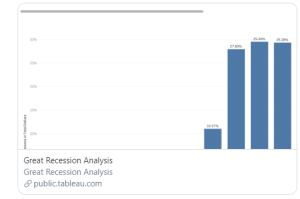

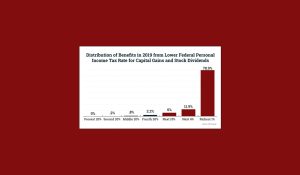

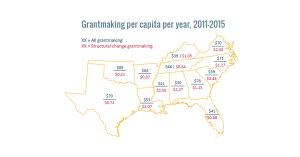

Funding, for starters, still has a long way to go. Institutional grantmakers devoted less than 20% of their dollars to low-income people, 15% to communities of color, and 3% to immigrants and refugees in 2021 according to NCRP analysis of Candid data. Research suggests only about 0.5% ($356 million) of foundation dollars are explicitly given for Black women and girls and 0.25% ($258 million) for LGBTQ communities.

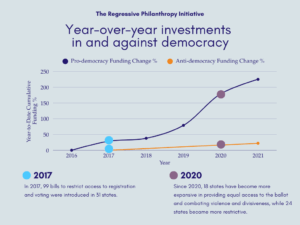

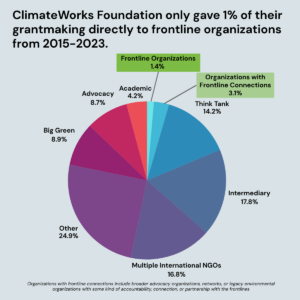

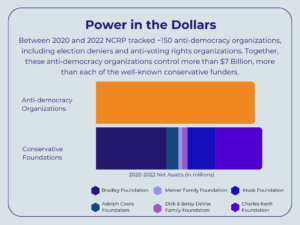

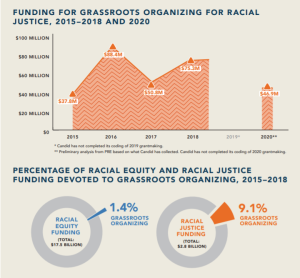

Grassroots organizers and social justice movement groups also struggle to find consistent funding year-to-year, especially in rural, conservative places. It’s a stark contrast to the long-term support far-right institutions have enjoyed for generations. Between 2015 and 2021, for example, we found that “more than two dozen nonprofits focused specifically on undermining electoral, liberal and economic democracy increased their fundraising three-fold to over $500 million per year.” In 2022 alone, just eight right-wing funders moved over $530 million to organizations working to roll back civil and human rights and undermine real pluralism.

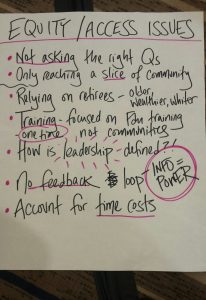

Even progressive funders are often unwilling to relinquish control for general operating support and multi-year grants. Many, if they’re honest, care more about the story their grants tell than the ecosystem they’re a humble part of.

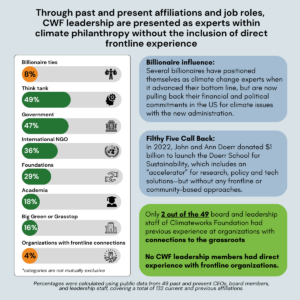

And while foundation staff are finally beginning to better represent the rest of the country, the foundation board members who call the shots at most foundations are decisively not a pluralistic reflection of the country’s demographic, geographic or ideological diversity – they’re usually far whiter, more male and more conservative than most Americans.

If anything, we’re on the threshold of an even more plutocratic era in philanthropy. Billionaires’ influence is rising, and donor transparency is on the decline. Thankfully, more funders embrace the vision of a just transition than they did a decade ago. But very few funders explicitly back alternatives to the dysfunctional capitalist system that bankrolled their rise.

When funding for equity and justice has been so inconsistent with philanthropy’s means, are we really surprised that we have plenty of work left to do? To suggest the solution, now, is to turn off the sprinkler when communities on the ground have long called for a fire hose is misguided at best and unconscionable at worst.

There’s progress worth celebrating, to be sure. But it’s important to see these as the hopeful breaks from the norm that they are. Otherwise, by over-stating their progress, funders will fail to accurately see the world in front of them, retreating to a supposedly safe corner of centrism that does not exist.

Appeasement is not a winning strategy.

There are plenty of funders who care more about supporting movements effectively than the false virtue of avoiding polarization, but they’re apprehensive. They look at last year’s affirmative action ruling, and they ask their lawyers to go much further. They see the shameless attacks on the Fearless Fund, and they claw back their own racial equity language. They see the spike in xenophobia and ask grantees to strike the word “immigrant” from applications. They see the outrage over the genocide in Gaza and pull funds from groups who speak out at all. They hear the incoming president promise to squash the hint of dissent, and they wonder how far they can retreat into the shadows. This is a mistake.

First, there’s no guarantee that a silent tongue or a defensive crouch will leave foundations and donors unscathed. Supposedly centrist funders may be surprised to find that it’s not just “woke” scapegoats with a target on their back. That’s why I was glad recently to see several industry groups take a stand, and that work must continue.

Second, at this moment, few are better positioned to take risks than philanthropy. Shoring up legal defenses is a legitimately good idea – but only if it enables bolder action and greater solidarity, not a white flag and bent knee.

Don’t just take my word for it either. Leading scholars of authoritarianism like Timothy David Snyder are clear: “Do not obey in advance.” When people “think ahead about what a more repressive government will want, and then offer themselves without being asked,” he notes, they’re only “teaching power what it can do.”

Instead, funders’ priority should be making sure people on the ground have what they need and more. Paul Di Donato at Proteus lays out several great recommendations, from physical and digital security to compliance and mental health supports. Grants and endowments, after all, are replaceable. Lives are not.

Beyond resistance

In truth, critics of a potential second Resistance™ usually make the same mistake many donors did with the first: Trump alone – as a man, as an administration, and even as a political moment – is not the point.

Resistance to harm matters just as much when a Democratic administration is the perpetrator. It matters when it’s a national headline, and it matters when it’s a local policy passed in an empty town council room. It matters when the impact is immediately obvious, and it matters when our kids or our downstream neighbors will feel it years later. Funders romanticizing recent resistance moments may miss the proven and successful generational organizing campaigns from decades past. They overlook people, often in some of the most repressive places, already building beautiful alternatives to the extractive world we have.

So – what then? What now?

At NCRP, we’re pursuing the same thing we’ve always wanted: a world where the public good prevails and anyone can thrive, regardless of wealth, privilege, or opportunity.

We’re pretty sure how to get there, too. We know from our high-quality research, through our lived experience fighting for justice – and because it’s not rocket science.

For nearly 50 years, we’ve found that funders have the greatest impact when they acknowledge their history, build transformative relationships, and honor communities closest to harm. The best ones build, share, wield, and yes, even cede power so folks can provide needed services, organize deeply, and build movements that challenge and remake the unjust systems that affect all our lives. And the few visionaries really listening?

They show up not just for a year or two at a time but for a generation and beyond, consistently returning the assets that were never solely theirs in the first place.

That necessary work persists, no matter who’s in office.

Let’s keep going.

Ben Barge is NCRP’s Field Director. In this role, Barge strengthens NCRP’s relationships with U.S. social movements and philanthropic organizations to move money and power to community-led advocacy and organizing.

![Demonstrators sit, with their feet in the Reflecting Pool, during the March on Washington, 1963]](https://ncrp.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/unseen-histories-ZtIcQfj33Q4-unsplash-1-720x1080.jpg)