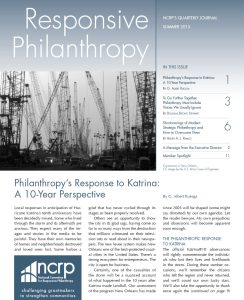

Community organizer and historian Corey Shaw reflects on how the stories that often don’t get recorded can push philanthropy to address its own history of harm.

As a researcher and community organizer, I have spent the last five years working with African American communities across the United States—mobilizing them towards achieving reparation and restorative justice for gross human rights violations as defined by international law.

At the start of my organizing career, I was focused on Washington, DC where I helped co-found the Black Broad Branch Project (BBBP) alongside descendants of two African American families who resided in Chevy Chase, DC from 1840 to 1936. In that effort, I was fortunate enough to have the support of descendants, the authors of Between Freedom & Equality (Barbara Boyle & Clara Green), and Historic Chevy Chase DC.

At the same time, I joined the African American Redress Network (AARN) where I began cutting my teeth in the national reparation movement. In my time with AARN, I became invested in understanding international law, reparations, remedies, and the political levers that can be used to achieve structural change and repair. I took this newfound perspective to communities in Virginia, Alabama, and Georgia. I worked with a community in each state to help them build a case for reparations and to mobilize towards real solutions. This work allowed me to bear witness to the struggles of a country which has failed to reconcile an often-hazy history of oppression, despotism, and neglect of Black folk and our communities. It was work that was often exhausting in the short term but enriching in spirit.

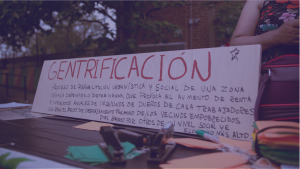

These experiences were all educational for me, both as a scholar and a young Black man. More than anything, though, they were perplexing. In each community, a complex web of land use decisions, community development, suburbanization, and industrial encroachment had stifled the growth of African American Communities. I struggled to understand how entire swaths of a community could be erased or end up surrounded by harmful industry.

Patterns of Exclusion

In Brown Grove, Virginia—zoning decisions and comprehensive plans completed by Harland Bartholomew & Associates inundated a historic Black community with a county airport. In Africatown, Alabama, the landing site of the last ship of enslaved people from Africa in the United States and the community those formerly enslaved folks built after emancipation. These land-grabs amongst industries have manufactured circumstances that have resulted in increased rates of cancer and a community that is surrounded by industry on all sides. In both instances, policy makers created the present circumstances using land use decisions.

These patterns around land use decisions hold true in Washington, DC—particularly as it relates to housing and the development of the city. As I’ve found my way back home as DC Legacy Project Director at Empower DC and as the Co-Chair of the DC Chapter of the National Coalition of Black’s for Reparations in America (DC N ‘COBRA), my work has come to focus on uncovering these lost histories of the city.

These patterns have reminded me of a few important things:

1) Our city looks the way that it does, demographically and architecturally, because of deliberate decisions—not by chance.

2) Our present circumstances were molded by a myriad of private-public partnerships which have forged diverse and homogenous communities across every demographic strata and it is those same partnerships that hold the potential to rectify the inequities present in the city.

3) Residents of the city have inherited these decisions, quite literally, for better or for worse.

The damage done by decisions I’ve enumerated in brief are cause for a revelatory change that begins with reparations.

Captain, George Pointer and His Enduring Legacy

To demonstrate the need, I want to share an excerpt of DC’s history that will make clear the harmful policies of the past and how these patterns have persisted into the present.

In an era of historical rediscovery, the nation is reckoning with histories long past that have been covered up or forgotten. For centuries, the history of Captain George Pointer and his descendants had been lost to time. However, thanks to the interest of the late, great, James Fisher, descendant of George Pointer, Tanya Hardy, his best friend, and two researchers in Barbara Boyle & Clara Green, that story has been revived.

Pointer, born enslaved in 1773, bought his manumission at the age of 19 and lived the rest of his life as a freeman—working for George Washington’s Potomac River Company. Captain Pointer, alongside other formerly enslaved and enslaved people, is responsible for the construction of [one of] the first maritime transportation networks in US History. His legacy also includes raising three beautiful, manumitted, children, captaining a fleet of boats up and down the Potomac and Shenandoah waterways with materials for the construction of Washington, DC. He also helped to plan and construct what is now the C&O canal and ascended to be the Supervisor Engineer for the Potomac River Company.

The collective history of the family at this moment is one of persistence and beauty in the face of a city that sought to deny them basic human rights. However, this is interrupted as the family’s life in a cabin in Montgomery County, MD bumps against the reality of being Black in America. You see, when George Washington died, the Potomac River Company went bankrupt and was acquired by the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal Company (hence the name C&O Canal). The acquisition was followed up with a route revision for the canal which would have seen the destruction of Pointer’s family cabin. Even in the early 19th century, the capitalist interest was seen to outweigh the rights of Black folk. Pointer penned a letter chronicling his life in great detail in September of 1829. Pointer and his wife, Elizabeth “Betty” Townsend, died in 1832 during the Cholera outbreak in DC. Their cabin was destroyed shortly thereafter.

Pointer’s life is one that highlights the indomitable spirit of African Americans throughout history, and the debt that this country owes. It makes plain two things which Washington, DC is actively reckoning with.

On one hand, it lays bare the simple fact that African Americans have always been integral to the fabric of the city. They toiled in fields and raised children during enslavement, made many of the bricks used during the city’s construction boom in the early 20th century, and have consistently enriched DC’s cultural heritage.

Yet, in spite of that fact, their positionality—that is, their proximity to economic opportunity and the treatment they receive in society—has been consistently undermined by private institutions and governmental actors (and factors) at the Federal and local level. African American communities have been displaced, sometimes repeatedly, in Washington, DC with the intention of building spaces that would be explicitly white. It is the latter, which has sparked a conversation around place making in Washington.

Dry Meadows, DC and the Vision for a White Suburb

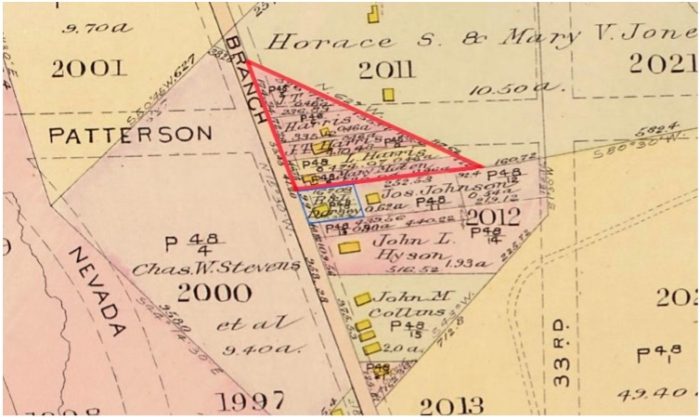

Mary Harris, the granddaughter of George Pointer, settled in the village of Dry Meadows, in what is today, Chevy Chase, DC. She and her husband, Thomas, bought that land in 1840. Their immediate neighbors, Laura and Robert Dorsey, were a family of Black folk who were related to Caroline Branham, the “dower slave” of Martha Washington.

The Harris family bought a parcel of roughly 3 acres and the Dorsey family bought a substantially smaller part.

Mary and her husband were farmers. They raised 4 children to adulthood and were married for more than half a century by 1890. Two of their sons, John and Joseph, had fought in the civil war—laying siege to Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy. In the late 19th century, the Chevy Chase Land Company (CCLC) laid plans to build a segregated, whites-only, suburb in Maryland. When the sons returned home from the war, they were helping to rebuild a community which had been attacked by the Confederacy in their absence. What they had not known was that by 1890, a new front in a different war would be opening. The racialized development of suburbs was on its way to Washington and Dry Meadows was one of the first communities in the cross hairs of landowners and developers looking to make top dollar.

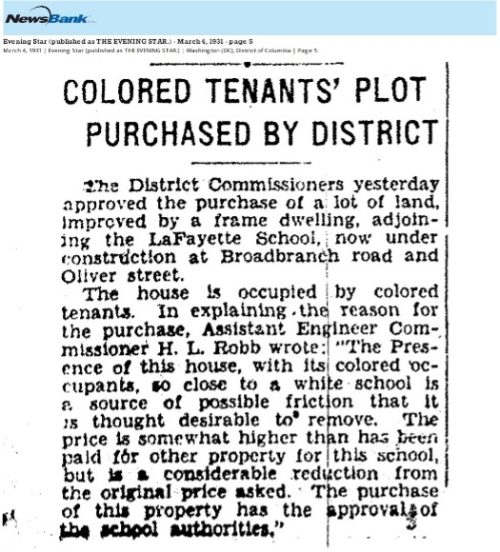

In 1928, after a successful Federal and local lobbying campaign from white residents of the new suburb of Chevy Chase, the National Capital Parks and Planning Commission (NCPPC) seized their land using eminent domain. Faced with the ultimatum of taking an arbitrary sum of money or nothing, The Harris’ were paid $6,862.50. The reasoning for the displacement of the village of Dry Meadows is made clear in a newspaper article of the time which notes “the presence of this house, with its colored occupants, so close to a white school is a source of possible friction that it is thought desirable to remove.”

They lost their home so that Lafayette Elementary School, then a segregated white school, could be constructed for the white suburb that had been built around them. This initial instance of land seizure sets forth a violent pattern of household instability and economic deprivation for both families.

Barry Farm: From Thriving Self-sufficiency to State Manufactured Poverty

After generations of displacement, Mary Harris’ descendants had gone from Chevy Chase (where today the average home price is about $1.1 million), to Reno City (where they were renters), to Georgetown, to Southwest (where they were displacing by urban renewal) and had landed in Barry Farm in the mid 1950s. It is clear, the city’s development is a story of serial displacement—as demonstrated in the history of the Harris family. However, this history of repeated removal is a story of African American communities. Many Black folks migrating from the old South and those who had been homeowners in Washington found their way into public housing communities in the early 1940s—for which in 20 years they were demonized as burdens of the state and later as welfare queens.

One such community was Barry Farm. The community was initially created by the Freedman’s Bureau in 1867 under the leadership of General Oliver Otis Howard, the namesake of Howard University. It was established as a space for African American civil war veterans and their families. Those veterans were able to purchase lots in a larger 375-acre parcel and build a community along the waters of the Anacostia River. During the 74 years that Barry Farm was a land-owning community, it was self-sufficient. In those early years especially, the Anacostia River was an economic engine for the community—the bank was frequented by fisheries who would sell fish in the community. Residents also farmed the back portion of their lots to provide additional wares for consumption.

It is critical to understand that Barry Farm as it was established was a Black community in the rural and overwhelmingly white enclave of Southeast Washington in post-civil war America. That comes with all of the horrors one might imagine of the South, as DC was (and is) a Southern city. Despite manumission, residents were still subject to discrimination, the risk of racial terrorism, and black codes of the time.

The community was impacted by two distinct but equally destructive development projects in the 1940s: the construction of Suitland Parkway and later the Barry Farm Dwellings. More than 100 families were forced from their land by the federal government to build the parkway as a connector to military installations in Maryland and the Nation’s capital. The rest of the community was cleared for additional development. What had been a land-owning, 375-acre, African American community was demolished and reduced to a 32-acre segregated public housing project for African Americans. The justification given by the National Capital Housing Authority (NCHA) at the time was that Barry Farm was a slum—and thus warranted clearing.

Despite the displacement, the newly named Barry Farm Dwellings and its residents persisted. This iteration of the community no longer had access to the Anacostia River as the Anacostia Freeway was built, cutting off direct access. And even if they had, the river had been so polluted by industry (i.e. old River Terrace PEPCO power plant, Kenilworth Landfill), that anything caught from the river would have been entirely unsafe to consume. Instead of farming their backlots, they had small back yards which led to an alley for trash pick-up.

Constructed between 1943-1944, The Dwellings, similarly to the community’s initial iteration, existed in immediate proximity to the segregated, white, Uniontown (today, historic Anacostia) in the era of Jim Crow. Again, bear in mind all that comes with that. The KKK had been photographed in Southeast Washington 20 years prior—and in the 50s white students and parents from John Phillip Sousa High School and Anacostia marched through the streets of Southeast Washington to protest integration with vulgar signs. While DC was not Mississippi—the challenges of being Black in America were still present, real, and disgusting.

In the early days, life inside the boundaries of Barry Farm was a blissful paradise for residents. Children played in the allies, there were yard presentation competitions, and double dutch leagues. Overtime though, following the trend of national austerity and disinvestment in the social safety net, Barry Farm began to fall into a state of disrepair. By the 1980s the community was unrecognizably dilapidated. This disinvestment was intentional and ultimately led to a plan to redevelop the community (and others) know as the New Communities Initiative. The NCHA began developing these in the late 80s. They became actionable in the 2010s, when relocation efforts began—moving residents of Barry Farm out of the complex so that they could demolish the community to build a mixed-income development. The justification for the demolition of the properties? As classified by Federal Law, Barry Farm was “dilapidated”. Thus, the mass disposition of the site was justified.

Empower DC, alongside a core group of residents, led the charge to try and save the traditional public housing model at Barry Farm. When it became clear that renovations were not an option (as a result of decades of neglect) and that neither the DC Housing Authority (successor to the NCHA) nor their federal counter part, The Department of Housing and Urban Development, had an appetite for a build-in-place strategy, Empower DC changed gears.

For us and the residents our mission became clear: if they won’t save the housing—we’ll make sure they never forget who lived here. A coalition of historians and preservationists was mobilized by Empower DC to seek an historic nomination for the property. While the developer, Preservation of Affordable Housing (POAH) wrote in “strong opposition” to the nomination, noting that the property had no inherent historic significance—they were overruled.

Today, the five buildings that sit on Stevens Road stand as a reminder of the successive iterations of the Barry Farm community and their legacy. Residents of Barry Farm led the fight to desegregate schools, bolster the social safety net for mothers on welfare, advised Dr. King, and helped found the National Welfare Rights Association. In the ranks of these people was one of the first Black women to receive a PhD, Fredrick Douglass’ children, survivors of the largest escape attempt by enslaved Africans in US history.

Denying this history in the interest of profit is disgusting. Feigning an interest in preserving buildings you fought to see rendered to rubble is a dereliction of morality and an insult to residents. More importantly, it demonstrates that the cycle of displacement continues.

The questions for nonprofits, residents, organizers, and philanthropic foundations alike are:

1) What can we do to stop displacement?

2) How can we uplift residents to help them keep up with the changing tides?

3) How does reparations fit into a larger and equitable plan for the city?

Bridging the Past and the Future

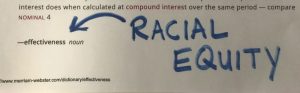

In response to uncovering these narratives, I have embarked on a journey of research and activism towards two ends: achieving redress for African Americans and their communities that have been impacted by historical harms and empowering Black communities that have been deprived of equal access to opportunity to be their own liberative advocates. There are structural inequities that are baked into the fabric of Washington, DC as a result of the inequalities of decades past (i.e. concentrated poverty in Ward 8, displacement of Black communities, discriminatory housing practices, et al).

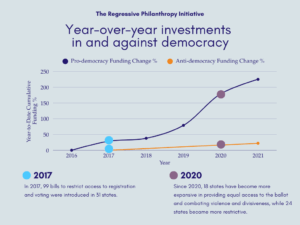

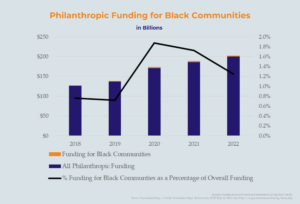

These instances of harm present an opportunity for philanthropic organizations, particularly those with a less than desirable relationship with principles of equality and equity, to help drive a fundamentally reparative movement.

In Wards 5, 7, and 8, there are African American communities that have suffered from disinvestment and a deprivation of resources—it is there where foundations can be critical agents of change by providing low-barrier funding opportunities for organizations that are working to bridge the several gaps for impacted residents and their neighborhood.

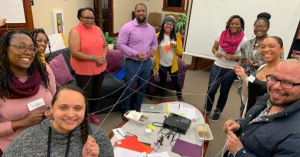

Organizations like Empower DC are directly involved in championing the cause of residents of Ivy City, Deanwood, and Barry Farm. Empower DC’s mission is to build the power of DC residents through resident-led community organizing to advance racial, economic, and environmental justice. Toward this end, we work with people with lived experience who can speak directly about the faults in the city’s systems and what should be done to repair them.

Empower DC is not the only group that is working to solidify community power through activism and community engagement. There are a plethora of organizations working to shine a light on the resulting inequities and potential solutions to policy missteps (W8CED, Anacostia Coordinating Council, Martha’s Table, Ward 8 Health Council, Anacostia Parks and Community Collaborative, and a litany of others.).

How Philanthropy Can Act

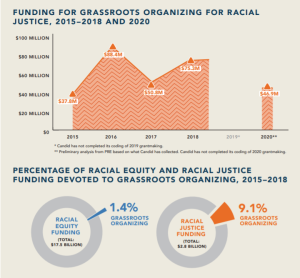

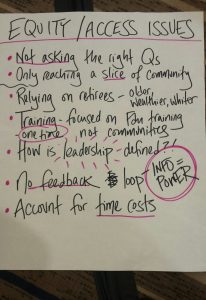

The challenge, of course, is not in the amount of community expertise that exists on this issue but the resources these organizations have to do their important work. The time has long since passed for institutions to not just take the recommendations of residents under advisement, but to actively find ways to bridge the gap between ideas and reality.

To usher a new era of change, foundations should:

- Remove barriers to applying for funding. Resources from the philanthropic sector are often tied to laborious reporting requirements and restricted to certain areas of focus. Foundations should make funds available with a low reporting barrier and few restrictions, allowing communities and the organizations supporting them to engage with what radical change may look like.

- Offer not just money, but a long-term change making relationship. Beyond funding, foundations are networking engines—open that wealth of connections to these groups that are working for fundamental change and redress. Imagine with communities like Barry Farm, what can the last remnants of the community do for the area?

- Be Active Listeners of Community Voices & Needs: Many past prescriptive solutions have, in many cases, already failed these communities. As noted in NCRP’s report, Cracks in the Foundation: Philanthropy’s Role in Reparations for Black People in the DMV, the role of funders in these spaces should be to join calls, participate in meetings, and listen—truly hear the needs of residents. To whatever degree possible, approach each community without a preconceived notion of the problem.

- Build towards self-sufficiency – If we’re going to honor the cultural heritage, what does that mean for restoring the community’s self-sufficiency? Stepping beyond normative funding models provides an opportunity for residents to direct and control their own futures in a way that they have been precluded from for decades.

For foundations, there is a chance to chart a different path forward—you have the chance to redress histories of discrimination, denial of housing, segregation, and unequal treat (to name a few) which have helped build your wealth.

When it comes to reparations and redress, we have to understand two adjacent notions. For one, if we are committed as a city to achieving racial equity—we too must be focused on the issue of reparation. For those that are struggling with the notion of reparations: the question before you, our city, and the nation is not what do you owe.

Rather the question is: what can you do?

Corey Shaw, Jr is a DC native with lifelong roots in Ward 7. Corey got his start working with communities in 2020 as the Co-Founder of the Black Broad Branch Project. He continues working on that project, advocating for reparations for two families whose ancestors were displaced from Chevy Chase, DC in 1928. Shaw also joined the team at Empower DC in 2023 as the DC Legacy Project Director focusing in on preserving the Barry Farm Historic Landmark in Ward 8.