Kanika A. Harris

Reflecting on Black Maternal Health Week’s theme “Building for Liberation: Centering Black Mamas, Black Families, and Black Systems of Care” Dr. Kanika A. Harris, MPH, the Director of Maternal and Child Health at the Black Women’s Health Imperative (BWHI) explores how the reproductive justice movement can support Black institutions, specifically Historically Black Colleges and Universities, and create new narratives for the future of Black birthing people.

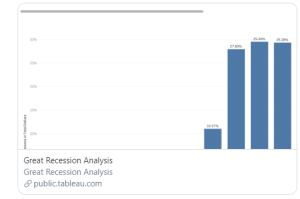

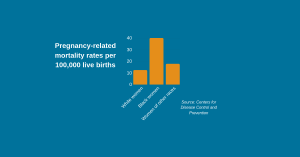

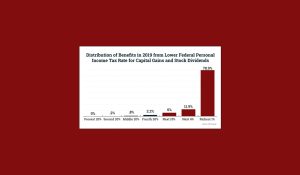

This year marks the 5th anniversary of Black Maternal Health Week. This week brings light to the disheartening disparities of Black birthing families that are most impacted by the US maternal health crisis while uplifting solutions that center their needs. The latest CDC data reports widening maternal mortality disparities between 2019 and 2020 resulting from the twin pandemics of racism and COVID-19.

An under resourced, but potentially powerful catalyst in tackling this issue are Black institutions, specifically Historically Black Colleges and Universities.

HBCUs as Catalysts for Better Care

For over 180 years Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) have provided incubators for Black students to thrive, fostering social and cultural identity, academic excellence, and world leaders. HBCUs always have been a site of resistance and liberation, educating former enslaved people and their descendants and galvanizing movements to fight injustices against Black people in the US and globally.

Ideally, HBCUs are well-positioned to lead the charge to improve Black maternal health by diversifying the workforce and training midwives, doulas, and public health professionals. Midwifery models of care have been shown to improve maternal health outcomes, decrease medical interventions, increase breast feeding rates, and improve satisfaction of birth.

However, out of 105 HBCUs there is only one accredited School of Public Health – Jackson State University. A “School of Public Health” is a prerequisite to have an accredited maternal and child health program, which leads to a lack of maternal and child health programs at HBCUs. There is not even one HBCU with an accredited midwifery program. Tuskegee University’s program closed in 1945 and the last HBCU that provided training closed in 2007.

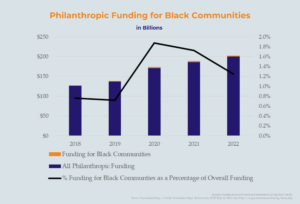

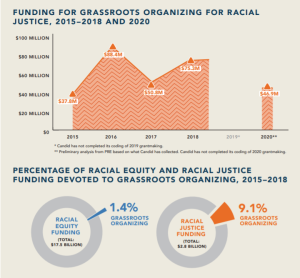

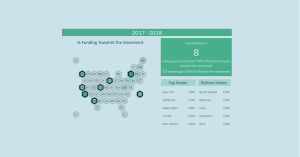

Funding plays a huge role in this. In the same article, Dr. Monica McLemore, Director of Birth Equity Research Scholars in the National Birth Equity Collaborative, explains that the accreditation process alone can take three to five years and the risk with limited funding and support is a lot for an HBCU to take on. HBCUs could lead that charge in Black systems of care but are cut at their knees because of structural racism that underfunds and divests from HBCUs, keeping them from producing leaders in maternal and child health.

Campus climate also plays a role. Some HBCUs are founded on conservative and Christian values that also deprive students of reproductive health information and care. A 2020 article from The Nation points out that only 12 HBCUs have Planned Parenthood chapters due to pushback and challenges to establish active chapters on campuses. Black women and girls at more conservative HBCUs are fighting for their own reproductive care and justice while also struggling to build maternal and child healthcare programs at their schools.

Making A Way out of No Way – Community Based Doula Programs on HBCU campuses

Organizations like the Black Women’s Health Imperative (BWHI) are filling the gaps to educate, liberate, and elevate the next generation of reproductive health leaders. BWHI started on Spellman’s campus in 1983 to answer the call of advancing health equity and social justice for Black women across the lifespan. The nonprofit organization identifies the most pressing health issues that affect the nation’s 22 million Black women and girls and invests in the best strategies to accomplish its goals through programing, policy, research, and advocacy.

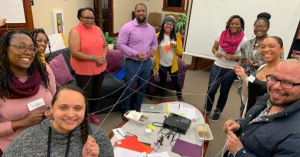

One of the BWHI’s signature programs is My Sister’s Keeper (MSK), which serves self-identified Black women ages 18-30 and currently has chapters on seven HBCU campuses. MSK focuses on programming to advance sexual and reproductive health, rights, and justice and women’s mental and emotional health, among other pressing issues.

To address maternal and child health, BWHI has developed a full spectrum community doula program for college students called N.O.U.R.I.S.H. (New Opportunities to Uncover Our Resources, Intuition, Spiriting, and Healing). There is evidence to show that doulas can improve health outcomes for pregnant women as trusted community members providing informational, physical, and emotional support through the birth and postpartum period. N.O.U.R.I.S.H. is a preconception doula training model to educate and expose young women to the importance of preconception health while giving them hands-on training and knowledge as doulas and community birth workers.

BWHI hopes to reengage communities in traditional frameworks of care and support that have protected Black birthing families for generations. Young women can provide support for birthing families and learn what it takes to show up to pregnancy healthy and whole. Our prevention model is “knowing is by doing.” Many young Black women are suffering with fibroids and heavy menstrual cycles and hidden warning signs of chronic conditions such as high blood pressure and Type II diabetes. BWHI’s signature high touch coaching model and heart health curriculum helps teach young women how to stay healthy through the lifespan and to support their family, community, and peers. BWHI also plans to expose students to careers in maternal and child health such as midwifery to invigorate a movement and address the disparities in maternal and child health training at HBCUs.

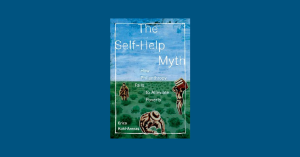

Like many health issues that disproportionately affect Black people, community members and advocates have been blind-sided by the depth of the maternal health crisis. Worse, we often lack key information, resources and opportunities to care for ourselves. Funding programs like MSK and N.O.U.R.I.S.H. arms Black birthing people with knowledge and skills to create a paradigm shift to fundamentally change how they care for themselves, their families, and our communities.