Last month, shots rang out in my beloved Brownsville. I’ve worked with the Brownsville community in Brooklyn, New York, for a decade, both on the ground – shoulder to shoulder with residents – and now, as a funder. In that decade, the news of shootings came all too frequently.

In the past, Brownsville was known for having the highest crime rates in New York City. But for those of us who have been working together, we had felt that we had turned the tide.

Investments in the neighborhood had increased, and crime had gone down.

And then the mass shooting happened on Saturday, July 27, “Old Timers Day,” an annual neighborhood family reunion.

On this day, there is an unspoken pact that all violence is put on hold. The mass shooting was a grim reminder that there is still work to be done.

That Sunday, The New York Times published an article about the death of Davion Powell, a teenager in Crown Heights, not too far from Brownsville, highlighting the nuanced nature of violence.

I read it as a work plan for change: The article highlighted key points in Davion’s life when the system failed him, when funders failed systems and organizations, and when government failed to care.

Any violence, either in Davion’s life or in the Brownsville neighborhood, is a manifestation of the breakdown in systems working together and the manifestation of deficits in investments in people, communities and neighborhoods.

This weekend of violence in the borough that I have called home for nearly a decade was followed by 3 subsequent mass shootings in California, Texas and Ohio in recent days.

The rate of these mass shootings have forced me to reflect on the role of philanthropy and its role in addressing violence.

When I first joined the New York State Health Foundation as a program officer, one of the first grants that I gave was to a violence prevention organization in Brownsville.

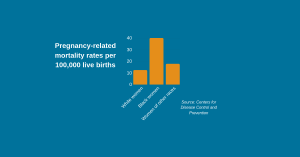

Having worked there for years, I had seen firsthand what violence does to a community. I brought with me one of the most important lessons from working on the ground: Violence is a barrier to physical activity, educational attainment, childhood development – to all the social determinants of health.

My reflections have led to some points that I hope other funders will keep in mind:

1. We need to take our own advice.

For a while, collective impact was all the rage in the nonprofit world. The idea of having a “community quarterback” as a convener in a community was an approach that numerous funders got behind.

But funders can use the collective impact approach across philanthropy, too. When was the last time that we had a deep, consistent relationship with other funders, beyond a specific project or board cycle?

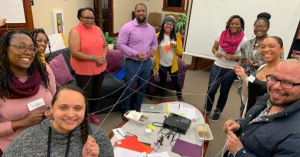

It was with this in mind that I developed the Brownsville Funders Collective, a collective of 7 funders who have interest in or are funding work in Brownsville.

We get together regularly to discuss key issues in the neighborhood, potential funding projects and key challenges.

We open it up to community experts to help shape our direction. It’s not that different than what we ask our grantees to do.

But this idea of organizing within our field is still novel. It needs to be the norm.

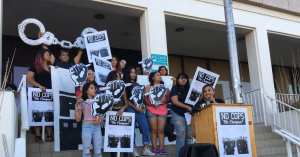

2. We need to be in solidarity with the work.

What does solidarity look like? It looks less like approaching the work with the mindset of “I not only believe that I am better than you, but I believe that I must intervene to stop you from becoming an even bigger threat and problem than you already are,” as Trabian Shorters wrote.

It looks more like the mindset of Lila Watson’s take: “If you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.”

Do we see our grantees as the “other”? Or do we see the grantees as manifestations of ourselves? Unless we see ourselves in our grantees, and vice versa, we will continue to perpetuate the cycles of violence in this country.

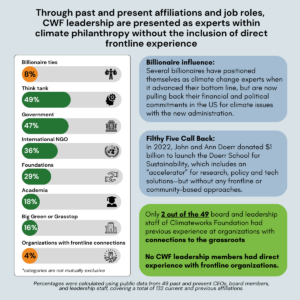

3. We need to change who we are as a field.

Part of the unintentional “othering” of our grantees comes from the fact that many folks who work in philanthropy have never experienced the problems that we fund, nor have they been a part of the solution.

Hiring folks who have worked on the ground, like myself, is a start. Valuing the knowledge of grantees beyond impact and results is even better. The North Star Fund has a great process around redefining expertise.

4. We need to iterate.

What the article about Davion highlighted so astutely were the very real nuances that lead to violence, and sometimes, death.

As funders setting up initiatives that span 5 to 10 years (if we’re lucky), with the answers already in mind and rigid funding guidelines, we leave little room for learning or flexibility as the work evolves.

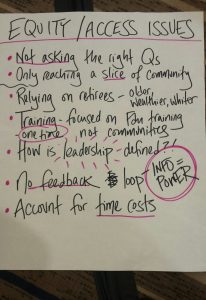

Let’s build in formal grantmaking processes for evolution. The Equitable Evaluation Initiative is a resource that can help with this work.

We run the risk of being reductive to addressing violence if we as funders fail to challenge ourselves to be in solidarity with the people affected by our work.

We need to widen the aperture to see the people and places, not just the issues. If we don’t, we run the risk of more weeks like the last.

Nupur Chaudhury is a program officer at the New York State Health Foundation. Follow @CautionChaud and @nys_health on Twitter.

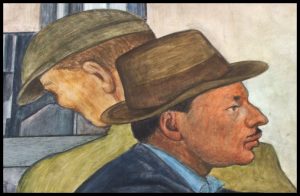

Photo by Charly W. Karl, used under Creative Commons license.