In the end, it all came down to Tiffany Lopez.

On September 29th, the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP) held its first-ever Philamplify Debate asking: “Can market-oriented reform strategies advance equity and empowerment in education?” Robert Pondiscio from the Thomas B. Fordham Institute argued the affirmative. In my opinion, within minutes, he lost. The trouble was Tiffany.

Mr. Pondiscio began by reflecting on his time as a teacher in a New York City public school, and an 11- year old student he had named Tiffany. Tiffany always did her homework, wore her uniform and kept her desk organized and neat. She was ready to learn. Though his principal told him “not to worry about Tiffany,” Pondiscio disagreed. He thought she deserved something more than what her public school offered.

(Editor’s note: Watch the whole debate on YouTube!)

This was Pondiscio’s justification for charter schools. Charter schools are a pillar of market-oriented education reform. The theory hails from Wall Street: create a vibrant market of privately-operated, yet taxpayer-funded, schools and allow consumers (i.e. parents and students) to choose among them. Shut down the ones that don’t perform and open new ones that might. Voila! Eventually, only successful schools will remain. For stock traders, this kind of model makes perfect sense. But markets don’t have a history of creating equity or empowerment in communities of color. For the low-income African American and Latino communities that are heavily targeted for charter growth – and school closings – it can feel a lot like some of the other great ideas imposed on them by Wall Street, like payday lending and sub-prime mortgages.

But back to our story. In Tiffany, Pondiscio saw a child who could thrive, if she could escape her public school. As he told us at the NCRP debate, when he moved from teaching to advocacy, he made a commitment to himself called the “Tiffany Rule.” Before supporting a new idea, he asks himself, “Would this work for Tiffany?”

The Fordham Institute is one of the nation’s leading voices for market reform in education. Mr. Pondiscio’s “Tiffany Rule” is consistent with the Institute’s view of chartering. In 2013, Fordham president Mike Petrilli argued in Education Week that charter schools should serve as an escape hatch for the “especially deserving poor.” The ones who have potential. The ones who do their homework. Like Tiffany.

But what about the 30 or 40 kids – whose desks might be a little messier, who might require a little more help with their homework – who surrounded Tiffany in that New York City school? Pondiscio’s principal may have been encouraging him to pay a little more attention to those kids, the ones who also deserve a public education. But Pondiscio never mentioned them.

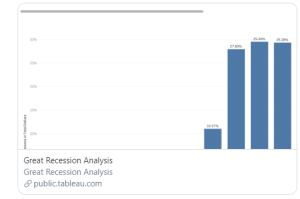

The research is clear: charter schools, in the aggregate, do not consistently produce better outcomes than traditional public schools. Some charters do well, others perform poorly and the majority offer basically the same academic outcomes as traditional public schools.

The research also says that three things tend to happen when lots of charter schools open up in under-resourced districts:

- Racial segregation increases.

- Students with special needs, like English Language Learners and students with disabilities, are underrepresented in charters and become disproportionately over-represented in traditional public schools.

- Traditional school districts are tasked with educating and providing services to these high-needs children with fewer resources, because the charter sector siphons more and more taxpayer dollars from their budgets.

This is not a fluke of market reform – it’s the foundation. Two parallel systems of schools are created: one public, with the obligation to serve all students; and another funded with public dollars but managed privately, with the incentive to attract more resourced students, cap enrollment and turn away kids who don’t “fit” the model. The inequity is inherent.

None of this is Tiffany’s fault. Nor is it the fault of the parents who choose to send their children to charter schools. But the children who don’t win a lottery to get into a charter school, or who are “un-chosen” by them or who choose traditional public schools – they are left behind and worse off because of the dual system.

It was painfully obvious in the debate that Mr. Pondiscio never made a rule for them. He never asks, “Will this help all my students?”

Markets create winners and losers. For free-market education advocates, philanthropists and hedge fund managers, the focus is on the winners, not on the rest.

In a debate on whether market-oriented education can advance equity, the market reform side lost the minute they invoked the story of Tiffany, the especially deserving student.

Leigh Dingerson is the author of Public Accountability for Charter Schools: Standards and Policy Recommendations for Effective Oversight, published in 2014 by the Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University, and Brought to You By Wal-Mart?, published by Cashing in on Kids in 2015.