Several Fridays ago I first learned that yet another Black man had been killed during a police stop in Baltimore, and I made no immediate effort to learn more of the story. It was a tale I had heard several times over, especially recently, and I suppose because of this it was easy to brush it to the side as I toiled through my daily tasks. The next night, after weekend errands and the premiere of my favorite show, I was finally ready to dive a little deeper into the story. I googled “Freddie Gray”, and as I poured over the Baltimore Sun article detailing the injuries he sustained, along with stills and a video of his arrest, I found myself weeping. If never before, my heart was broken. I couldn’t believe that there was a fellow human being who endured such brutal treatment at the hands of our nation’s protectors.

And while I am not the only person moved to tears by this tragedy, I’m also not the only one skilled at compartmentalizing these ongoing, almost daily occurrences of racism. After all, a few major events went off without a hitch that weekend. During the Orioles game that took place the following week, a fan interviewed by CNN casually mentioned he had to park several levels up in the parking garage to protect his vehicle from the demonstrations in the streets below. The contrast between this baseball fan’s concern for his car and the concern of protesters just outside the stadium’s gates, entangled in a daily fight to defend their lives, is telling of the privileged versus non-privileged racial differentiation that is still prevalent here in America.

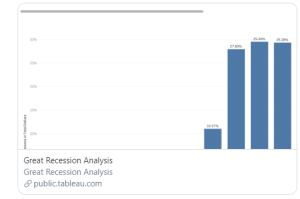

Some say that this stark contrast is a product of a capitalistic society, and I suppose just like there’s no crying in baseball, there is no crying in capitalism. Our free market economic system plays an invisible role in our lives, quietly controlling price and production levels through the creation of competition. As we have seen historically through the booming American economy and the creation of the wealthy elite, capitalism spurs great growth, but it also has the ability to cast dark shadows, especially when laced with the overt racism of our past or today’s more subtle implicit biases. And that is why it’s so important that the market-based approach has made its way to philanthropy, etymologically, the love of humanity. When economic, social, political and now philanthropic decisions are based on figures and bottom lines in a world of profits and competitions where only the strong survive, there is little room for fuzzy feelings. And in this scenario where people have marched, voted, peacefully protested, been beaten, tried to get jobs and own homes, were redlined, tried again, tried again, and finally tried again, does the answer for equal opportunity call for our Webster or our Barnhart?

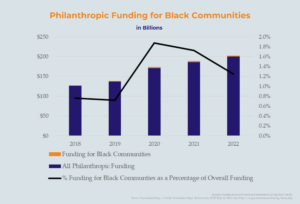

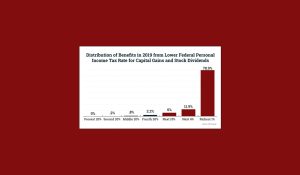

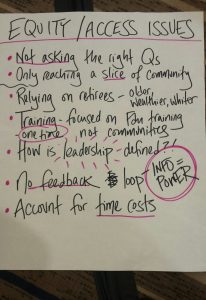

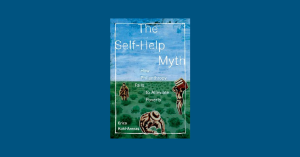

The problem with the market, as noted by Boston University sociologist and author of The New Prophets of Capital Nicole Aschoff, is that it rarely produces an evenly distributed result. This is okay with regards to nonessential luxuries and commodities, but when it concerns issues like “health, education, [and] the ability to have a house,” market-based strategies are divisive and fall short. For those of us who believe that these aspects of life should be rights and not privileges, the natural effects of the market are not enough. The cries of We Shall Overcome and the shouts of Black Lives Matter both have the same underlying question: Who do I have to be for America to love me? Who do I have to be for philanthropists to include me in the “love of humanity?” Isn’t it a disservice to the movement for equality to look for a solution to people’s pain through the privileged, limited results of the market?

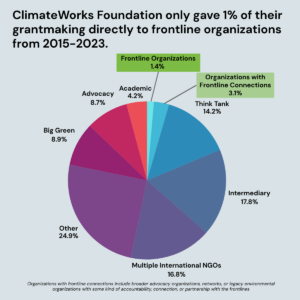

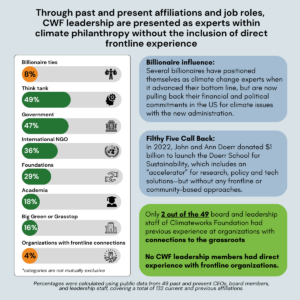

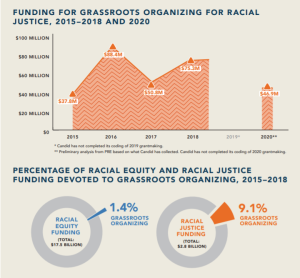

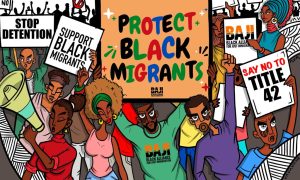

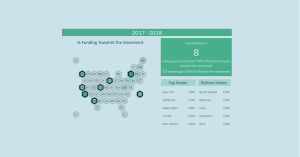

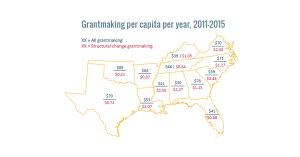

The problem with a market-based approach to philanthropy is that it doesn’t seek to address why our well deserving fellow human beings, our brothers and sisters, were left out of the equation in the first place. That’s why it’s important for grantmakers to fund the advocacy work vital to creating lasting change, such as the grassroots groups behind the Black Lives Matter movement. The Movement for Black Lives Convening this weekend in Cleveland is a clear example of how far the movement has come in the past year, and grantmakers who have provided general operating support and funds for advocacy and grassroots work have been a tremendous help. Such support may not make sense from a market-based perspective, but funding advocacy and organizing can provide the answer that many in this country have long been waiting for.

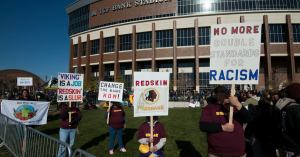

The 2015 version of separate but equal – where we believe we’ve made much progress in dealing with racism, ignoring the very real double standards that exist for education, treatment by police, job and economic opportunities, and the like – is simply not good enough. There is a segment of people in this country exhausted from 150 years fighting every day to be valued, treated with decency, respect and love. We, the lovers of humanity, have to work together to declare this the 12th round of the match. We as a nation are better than what we’ve allowed and settled for. Enough is enough. The time for true equity is now.

Janay Richmond is a field associate at the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP). Follow @NCRP and @JanayRichmond1 on Twitter.