Renowned for the connections he made between poverty and repressive government in Brazil, Archbishop Hélder Pessoa Câmara once said, “When I give food to the poor, they call me a saint. When I ask why the poor have no food, they call me a communist.”

This is one of my favorite quotations, because it forces me to take a pensive – and uncomfortable – posture. Specifically, it leads to several questions that get at how social justice philanthropy can best address the needs of underserved populations.

(1) Should we care if we are called saints or communists?

I find it sad but unsurprising that Archbishop Câmara received that response. More than that, I’m awed by his perseverance in the face of criticism.

How can we ensure that our human desire to be accepted by others doesn’t thwart us from asking tough, important questions, such as “Why are people hungry?”

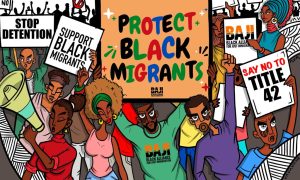

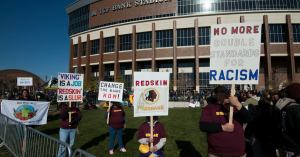

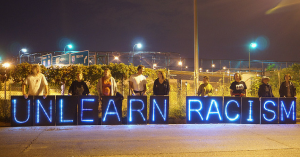

When we try to change the status quo, we might find ourselves labeled communists, instigators, advocates, organizers, radicals, rabble-rousers or other loaded terms. When this inevitably occurs, let’s refuse to be hurt or offended. Instead, we can choose to wear those terms as badges of honor. After all, many of history’s most lauded visionaries and influential leaders were once called names like these, too.

(2) Why do we avoid tough questions?

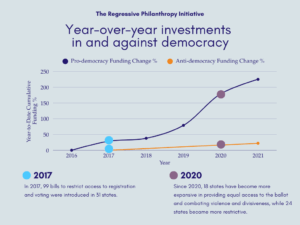

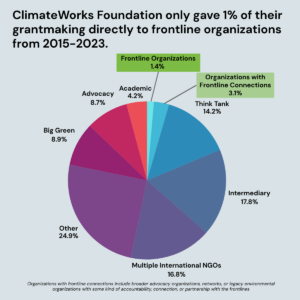

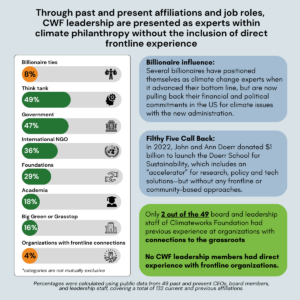

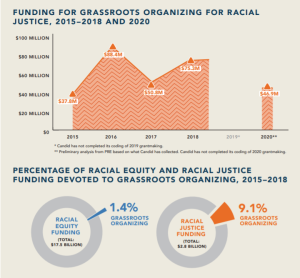

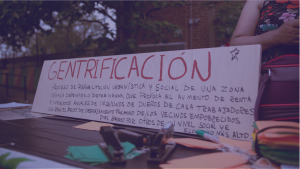

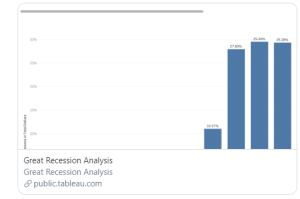

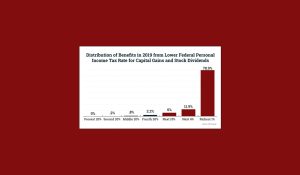

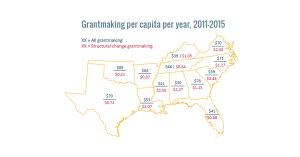

I wonder how many of us in philanthropy work on issues related to lower-income populations, whether it’s through the lens of hunger, education, health, housing, environmental justice, arts access, aging, youth, democracy-building and other issues. Many of us fund programs that provide food, shelter and clothing, but there is also a great and growing need to address the root causes of why people are hungry, homeless and impoverished. You might be surprised to learn that the median amount of grant dollars that the 1,100 largest foundations allot to social justice strategies is only two percent. This small sum includes, but is not limited to, funding for advocacy, community organizing and civic engagement.

I posit that very few people oppose a discussion about “justice” or have visceral reactions to the word “social.” Yet, when those two words are combined, in a certain order, many people become uneasy. Posing questions about social justice or root causes of problems of poverty and hunger can be hard and uncomfortable, but avoiding those conversations won’t help philanthropy make a long-term impact on the issues we care about. This is especially true when those of us who lead the conversation are neither impoverished, nor hungry, which leads to the final question.

(3) Where are the poor?

As I mentioned above, so many of us in philanthropy are focused on lower-income populations, but where are the people we seek to help? I work in safe, air-conditioned, accessible and well-lit office – for which I am grateful. Yet, I pass at least five homeless people every single day on my way to work. I am not walking with the poor like Archbishop Câmara, Mother Teresa or talented community leaders and organizers of today. I am walking past them. Thus, I, too, am susceptible to a sort of altitude sickness, even as I encourage foundations to be responsive to the needs of the communities they serve.

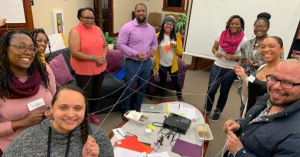

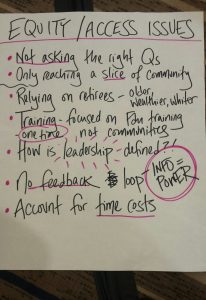

How can we integrate the perspective of the communities we serve in our reports, not just talk about them? How can we include their voices at our conferences, not just pass them on the way to our conferences? Are they represented on our boards or staff? Without objection, women’s foundations typically ensure that women serve on their boards. Employing the same thoughtful rationale, it could make a lot of sense for a foundation focused on underserved communities to include members of these communities on their board, staff or advisory committees.

This series of questions could apply to any kind of work in philanthropy. Again, these are hard questions for me to ask myself, and I do not pretend to have all the answers. Yet, I do believe that a good start might include: (1) asking the right questions, which will likely be uncomfortable, and challenging and (2) redefining who is included in the decision-making process.

If any of you pose similar questions to yourself or your colleagues, please share with NCRP and the larger philanthropic community. I would highly recommend the outstanding and much-needed publication, “Words Matter,” by Grantmakers for Southern Progress, which identifies some great ways to approach questions and conversations like these.

Christine Reeves is senior field associate at the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP). Follow @NCRP on Twitter.