How many times have we heard the quip that “cutting out the middleman” would be easier, cheaper and more efficient? This idea hasn’t quite taken hold in philanthropy. Because of the distance between foundations and the communities they serve, nonprofit staff often must serve as “gatekeepers” for foundations, taking away needed time from their work to impact systemic, long-term social change.

Take for example Ron,* the director of a small nonprofit that organizes tenants in a city with one of the largest wealth gaps in the nation. Ron has worked with a particular group of disadvantaged residents for years, spending countless hours building trust with people who are weary of outsiders. Together, they have started a resident council, held city officials accountable for property maintenance and provided career and other training for members of this community.

Ron worked with community leaders to secure a grant from a community foundation to fund senior programming. He organized planning meetings so the residents could lead the project design, and the foundation’s program officer even came to one. When they received the grant contract, Ron reviewed the terms with the community volunteers, and they agreed to them.

However, when it came time for implementing the program, Ron found himself in the awkward role of gatekeeping middleman. He quickly realized that, while the community leaders signed off on the contract, they hadn’t anticipated some of the repercussions of the terms they agreed to. For example, one leader had an elderly relative visiting for the summer, and was angry when Ron reminded her that her relative could not participate because he was not a resident. Other leaders wanted to expand the number of participants, as the limits set by the foundation omitted half the senior population of the community.

Ron attempted to negotiate these points with the community’s leaders and educate them about the grant process, such as the restrictions around spending grant money. He explained why they had to adhere as closely as possible to the line items in the budget. He reminded them of the foundation’s grantmaking strategy, of working consistently with small groups of people over time.

As more conflicts arose, some of the leaders began to question Ron’s loyalty. They said that it seemed unethical to them to provide an opportunity for some seniors in their community and not others. The leaders offered creative solutions, suggesting ways more seniors could be served, such as holding one-time workshops that different seniors attended each time, instead of the agreed-upon ongoing workshops for the same group of seniors. They wanted to know what would happen if they spent the money in different ways. And they often reminded Ron that everyone hooks up their friends and family, so why shouldn’t they?

The volunteers held Ron accountable for requirements that were set by the foundation. When I asked Ron if he allowed the leaders to bring their concerns directly to the foundation program officer, he responded that he was expected to handle these conflicts.

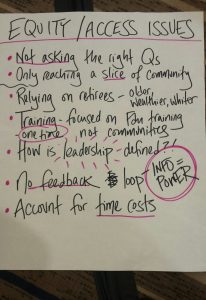

By requiring Ron to play the role of a gatekeeping middleman, the foundation is missing a chance to gather valuable qualitative data about the impact of its approach to grantmaking. Foundation staff likely developed their strategies about senior programming based on hard research, but did they have information about unanticipated effects on community relationships, trust and values that their requirements would have? Did they consider community assets that would need to be sacrificed in order to conform to the foundation’s prescriptions?

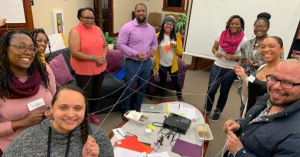

This is also a missed opportunity for capacity building. Clearly one meeting with the program officer was not enough to build trust to a point where community leaders could be fully honest about their program design ideas and needs. Residents who are skeptical about the foundation’s processes – such as contract development, the consequences of breaking contract and the necessity for line-itemed budgets – could learn a lot by hearing directly from the foundation. And by directly engaging with the residents more often and addressing questions about why the foundation set the requirements it did, foundation staff could build trust while strengthening its partnership with the community it serves.

When questions of a foundation’s accountability start to detract from an organizer’s true work of organizing, training and designing and implementing programs, it inevitably leads to the question of whether the role of intermediary is an appropriate one for nonprofits to play. What do you think? Should foundations stop relying on nonprofit leaders as intermediaries? Should they engage more directly with the constituents they seek to serve? Tell us in the comments.

*Names and other details have been changed.

Jeanné Isler is field director at the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP). Follow @ncrp on Twitter.