Three years (yes, only three) have passed since the U.S. Supreme Court issued the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision, unraveling nearly 50 years of precedent and stripping away the constitutional right to abortion care and services. In those three years, abortion access has not just been diminished; it has been criminalized, surveilled, disincentivized, and twisted into a weapon of confusion, shame, and fear.

But the frontlines of abortion access have made it loud and clear that we are no longer in a post-Dobbs moment. We are in a rebuilding one, and it requires clarity, courage, and community.

As a Black reproductive justice organizer working parallel to the philanthropic sector, I hold many contradictions. I am both a survivor of this system and a strategist inside it. I’m brought into decision-making spaces, but the dynamics in the room often leave me feeling like I have to earn my right to stay. But I stay because I believe deeply in the power of moving resources toward liberation, especially when done in solidarity with the movements that got us here and will continue to lead us forward.

At NCRP, we have spent the past five years walking alongside abortion leaders, deepening our accountability, and confronting our own missteps in this work. We’ve studied what didn’t work, we’ve amplified what did, and we’ve consistently reminded this sector that abortion is essential healthcare and funding it is both legally sound and morally urgent.

In this moment, philanthropy has a choice to make. Will you stand behind sanitized statements and cautious commitments? Or will you meet this moment with the kind of bold, transformative solidarity that reproductive justice movements deserve? Right now, we are witnessing the resurgence of a fierce and targeted backlash against the most vulnerable, facing the most obstacles to abortion access.

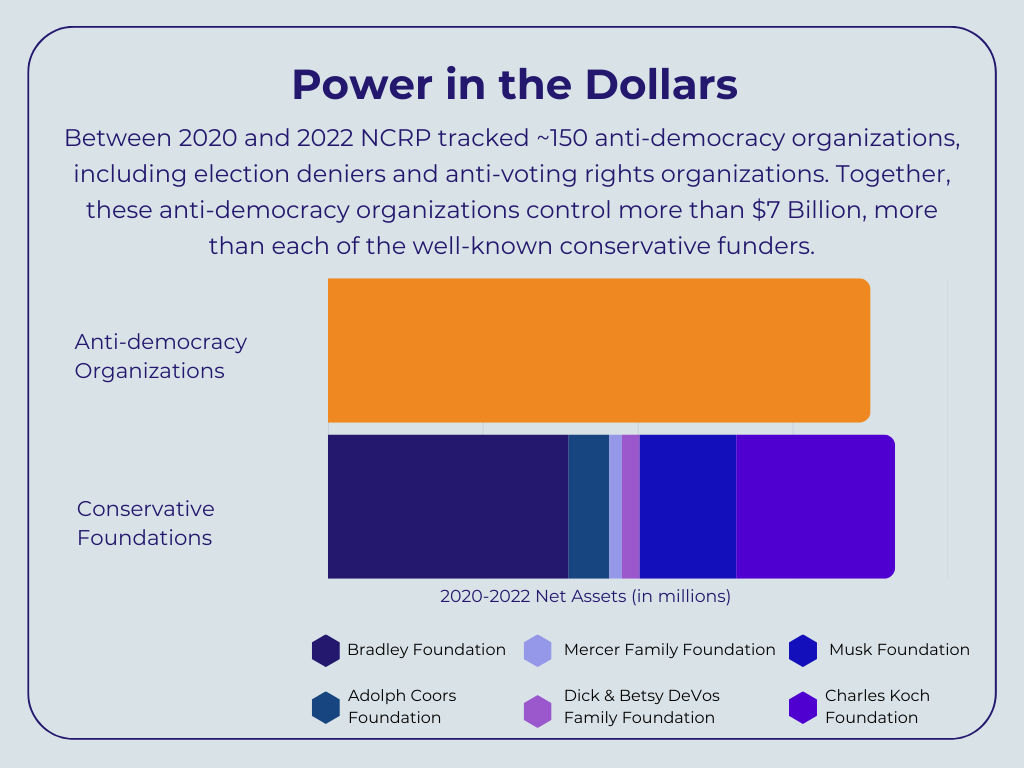

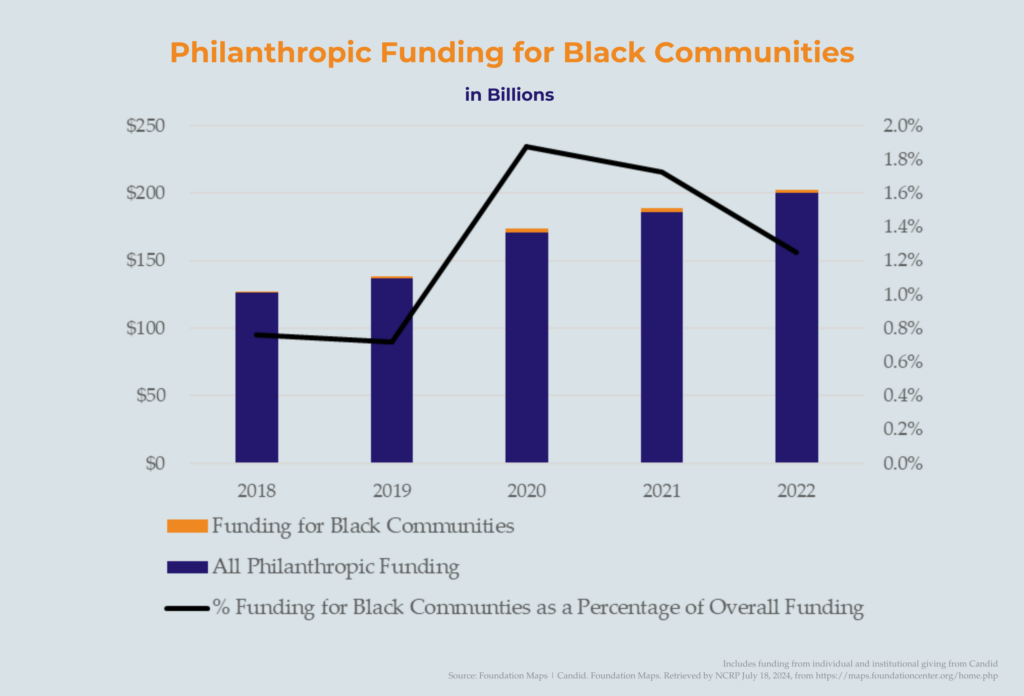

The number of states enforcing total or near-total abortion bans has doubled. While Crisis Pregnancy Centers (CPCs) are taking in eight times the support of actual abortion providers in 2021. Meanwhile, CPCs, misleading, anti-abortion institutions, have grown in both scope and funding. These organizations weaponize fear through disinformation campaigns, racism by co-opting Black maternal health narratives and practices, and faith through shame-based counseling that manipulates and controls. Their rise is not a side effect; it is a strategy. A moment that requires funders to get clear about who they are funding and why. Rebuilding trust with the people most harmed by Dobbs starts with action, not optics.

Watch: Emergency Funder Briefing After SB8

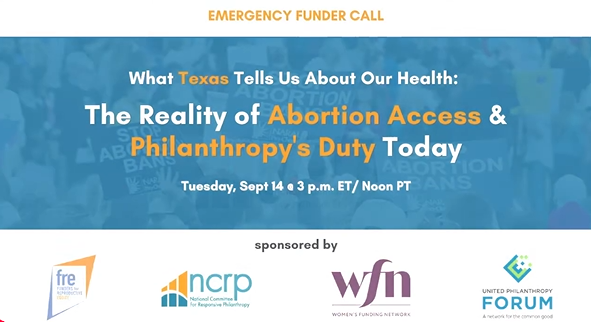

To help funders understand the stakes and legal realities on the ground, NCRP, alongside Funders for Reproductive Equity (FRE), Women’s Funding Network (WFN), and United Philanthropy Forum, co-hosted an emergency funder call following the implementation of Texas SB8. This moment of legal crisis revealed not just how quickly rights can be stripped, but how essential coordinated philanthropic response is.

In the video, you’ll hear from Rosann Mariappuram (Jane’s Due Process), Elise Belusa (Tara Health Foundation), and Dr. Ghazaleh Moayedi (Pegasus Health Justice Center) as they offer concrete insights into how philanthropy can show up, not just legally, but with urgency and impact.

As an abortion organizer at the margins and intersections I exist in, I know that fear—particularly fear masked as legality—has long been used to stall liberation. Philanthropy is not exempt. But let’s be clear, while the legal terrain may be complex, it is not impossible. In fact, you have more room to act than you think.

Know your rights. Here are ten truths every funder must understand to move money boldly, safely, and legally in support of abortion access.

- The Hyde Amendment Restricts Federal Dollars. Not Yours.

The Hyde Amendment prohibits the use of federal funds for most abortion care, but that restriction doesn’t extend to private or philanthropic giving. By no means are private foundations bound by Hyde, or the restrictions implemented by the state. Stop letting government limitations create artificial boundaries in your strategy.

- Advocacy, Education, and Organizing Are Fully Permissible Under 501(c)(3) Law.

You can fund voter education, you can support policy changes, and you can even invest in organizing. The IRS permits 501(c)(3) nonprofits (and their funders) to engage in a range of grassroots organizing. What’s restricted is lobbying. You know the difference between community-building, grassroots-organizing, and lobbying activities. A risk-averse definition of lobbying is so broad that it could limit very legal grassroots organizing work. Don’t let conservative interpretations prevent you from investing in the broader abortion framework.

- Unrestricted Giving Isn’t Just Easier. It’s Safer and Smarter.

Restricted funds can create legal risk when they’re too narrow or specific, while general operating support gives abortion organizers and providers the flexibility to respond to real-time threats, needs, and opportunities, while protecting both them and you from compliance issues. Unrestricted money is not a luxury; it’s a shield and a strategy.

- Practical Support Is Fundable and Essential.

Need to help someone get to a clinic? Pay for their hotel? Cover childcare? You can fund all of that. Travel, lodging, abortion doulas, childcare, and translation are not “extras.” They are essential infrastructure. Private funders are legally allowed to support these services, especially through general support grants or our intermediary partners.

- Legal Defense and Safety Planning Are Fundable Too.

Many of the people doing abortion work are under surveillance or facing criminalization. Funders can and must support grantees’ access to legal counsel, digital and physical security, and risk mitigation strategies. This is harm reduction.

- Understand the Legal Landscape.

Abortion is being criminalized across state lines, and it is essential that funders stay informed on state-specific laws that could impact grantees or partners operating in multiple jurisdictions. Partner with legal experts to understand where your funding flows and what risks may exist, but don’t assume risk means inaction.

- Private Philanthropy Is Not Governed by Title X or Medicaid.

Title X and Medicaid have strict federal rules, but they don’t govern your private giving. You are not constrained by those systems, even when your grantees operate within or alongside them. We urge you not to confuse what’s prohibited for the government with what’s prohibited for you (the funder); they are not the same.

- Don’t Let Bad Legal Advice Drive Your Strategy.

There is a difference between legal counsel and fear-based decision-making. We’ve seen too many funders have accepted overcautious interpretations of nonprofit law, missing critical opportunities to act. Legal risk is real, but it’s navigable when working with reproductive justice-informed legal teams who understand movement realities, not just institutional liability.

- Yes, You Can Fund International Abortion Work with Care.

The Helms Amendment and related policies do not ban all international abortion funding; they ban the use of U.S. foreign assistance for abortion services. But you, as a private funder, can support reproductive health work globally when you are following the wins of intermediaries and advisory from compliance support. Don’t abandon the global South out of confusion.

- Storytelling Is a Legal, Strategic, and Powerful Investment.

You can fund media, you can support podcasts, you can be creative, and invest in art, research, documentation, and narrative strategy. These are not just legally safe, but they are essential for shifting culture, fighting stigma, and reclaiming power. We don’t win without story.

We urge our philanthropic peers to:

- Fund without restriction. General operating support is not only safer for your grantees, it is smarter for the work.

- Support practical care. Travel, lodging, abortion doulas, and childcare are not extras, they are critical infrastructure.

- Invest in narrative power. The backlash has always been a battle for hearts, minds, and control. Narrative strategy, digital storytelling, and cultural organizing are essential to long-term change.

- Back risk mitigation. That includes legal defense, security planning, and care teams for those under surveillance or threat.

- Increase legal literacy. Cut through fear-driven misinterpretations of 501(c)(3) law. Don’t let bad legal advice drive your strategy.

- Join us in building a deeper, collective analysis. NCRP’s Funding the Frontlines Roadmap, We Told You So, and Building an Uncompromising Movement for Abortion Access are living documents. Study them. Debate them. Use them to strengthen your own work.

And just as important, show the hell up. Join movement spaces willing to challenge how wealth is used, so your proximity to it becomes a resource for shifting power and deepening resistance. This fall, meet us at the Women’s Funding Network’s Feminist Funded conference on the Capitol steps. Become a member of Funders for Reproductive Equity and engage in values-aligned strategy building alongside movement leaders and fellow funders. Attend the CHANGE Unity Summit. These aren’t just convenings. These gatherings are laboratories for collective learning, and more importantly, accountability.

I do this work grounded in a reproductive justice framework; because the vision built on the right to have a child, not have a child, and raise a child with dignity requires more than legal protections. It requires resources, imagination, and care. That’s why I also root my organizing in healing justice because our sector cannot be brave if we are disconnected from our own humanity, our own lineages of resistance, and the wisdom of communities that have survived genocide, eugenics, and abandonment.

Philanthropy must match the scale of this moment with the scale of its response. The anti-abortion movement is not confused. It is coordinated, well-resourced, patient, and winning. But we can change that.

To our frontline partners and movement siblings: We thank you. You are the force behind this movement, and no court can match the strength of your conviction

To funders: We ask that you declare yourselves a safe space for abortion funding. That you rebuild trust with the field, not through branding exercises, but through budget lines. That you name and confront the ways that the sector’s aversion to risk has delayed urgent care, undermined movement leadership, and let CPCs flourish in the vacuum.

You don’t have to do this alone. In fact, you shouldn’t be. Declare your commitment and invite your peers to make their institutions a safe space for abortion funding.

In honor of the 3rd anniversary of the Dobbs decision, let’s rebuild what Dobbs tried to destroy.

Brandi Collins-Calhoun is the Movement Engagement Manager at the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP). A writer, educator and reproductive justice organizer, they lead the organization’s Reproductive Access and Gendered Violence portfolio of work.