Local Foundation Funding (2020)

Local Foundation Funding (2020) | Interactive Digital Dashboard |

The recent coronavirus pandemic has put a spotlight not only on the longstanding inequitable cracks in the nation’s health care system, but also on the vast gulf in resources different communities have on hand to respond to immediate emergencies.

The personal health and economic impact of COVID-19 is felt most acutely by marginalized people, including the millions of immigrants and refugees that have been disproportionally impacted, unfairly scapegoated and, in many cases, excluded from relief packages.

The pandemic has exposed the deep-rooted inequities that have constituted an ongoing crisis for many communities in America. Many immigrants and refugees are people of color who are over-represented in the ranks of essential workers who are at highest risk of contracting and dying from the virus.

The unique vulnerability of these communities to the disease is directly related to years of increasing xenophobia in state, local and federal policies combined with historic levels of anti-immigrant rhetoric and violence since the election of Donald Trump.

We expect local charitable institutions to be first in line to service the needs of our communities and especially of the most vulnerable among us. One measure of local philanthropic responsiveness is the degree to which their grantmaking reflects local community demographics.

An NCRP analysis of the latest publicly available data shows that, as a whole, the largest local foundations are failing to provide financial support that is proportional to the number of immigrants and refugees in their states and the threats they face.

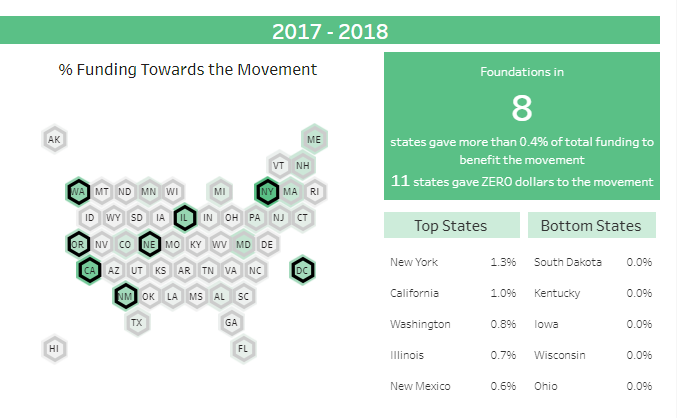

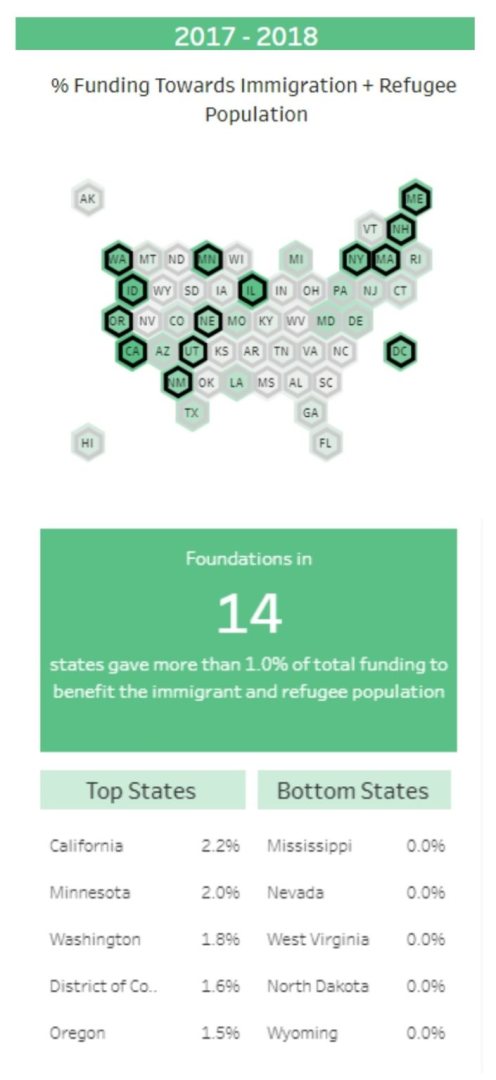

While immigrants and refugees represent 14% of the nation’s population, local foundations gave barely 1% of their total grantmaking to benefit these communities in 2017 and 2018.[1] Furthermore, less than half of a percent of local funding is for pro-immigrant, pro-refugee movement groups engaged in organizing and advocacy.[2] In fact, more than 50% of the largest local grantmakers of each state didn’t even fund one of these movement groups.[3]

The numbers mirror what NCRP discovered last year in its first Movement Investment Project brief, the State of Foundation Funding for the Pro-Immigrant Movement. That brief reported that barely 1% of funding from the nation’s largest U.S. foundations went to organizations serving immigrants and refugees, with national networks and grassroots groups being particularly underfunded.

What this year’s analysis and accompanying data tool does is place that national trend in a state-by-state context, identifying just how much work local funders and leaders need to do to ensure that all communities get the support they need to thrive.

THE UNJUSTIFIED THREAT TO IMMIGRANT & REFUGEE FAMILIES

Over the last 2 decades, billions of taxpayer dollars in Democratic and Republican administrations have been budgeted to attack this population. A combined $23.8 billion in 2018 was set aside for the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) agencies, an increase of 39% from 2012 through 2018. Not surprisingly, the Migration Policy Institute has found that removals and returns carried out by CBP and ICE in 2018 increased 17% and 13%, respectively, from 2017.[4]

The Trump administration has intensely sought multiple avenues to harass and intimidate both documented and undocumented people living in the U.S. This includes:

- Efforts to end Temporary Protected Status (TPS) and Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA).

- Imposing a wealth test for legally present immigrants and their families that punishes sponsors who may have used social safety net programs like Medicaid or Supplemental Nutritional Assistance Program (SNAP).[5]

- Overseeing a 35% increase in backlogs for green card processing.[6]

- Making application errors, missing paperwork and even pregnancy grounds for visa application and renewal denials, which can be used to trigger nearly instantaneous deportation orders with limited opportunities for appeal.[7]

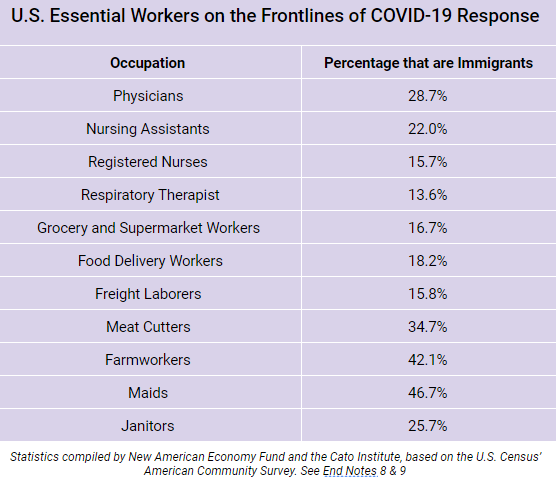

Amidst these attacks, immigrants and refugees are risking their lives for their communities daily. They are over-represented among the ranks of workers that are on the frontlines of responding to the current coronavirus pandemic.

The New Economy Research Fund notes that as many as 16.5% of all health care workers in the U.S. are immigrants, including home health aides (36.5%), physicians (28.7%), nursing assistants (22.0%), registered nurses (15.7%) and respiratory therapists (13.6%). They are also a key constituency of essential non-health care workers, like grocery and supermarket workers (16.7%), food delivery workers (18.2%), freight laborers (15.8%) and butchers and meat cutters (34.7%).[8]

Even the libertarian Cato Institute points to the critical role immigrants are playing, noting the important work immigrant farmworkers (42.1%) are doing to ensure that all Americans have food, and how maids (46.7%) and janitors (25.7%) are on the frontlines of making sure that public spaces, businesses and homes are cleaned and disinfected. [9]

Foundations can rise to meet the challenge of the current moment by funding these communities and this movement at levels proportional to the threats they face and their share of the state population. No matter a foundation’s focus or geography, a robust movement that supports the rights of this community is critical to securing safety and wellbeing for all.

BY THE NUMBERS [10]

THE GOOD:

- There has been an increase in total funding during the Trump era, with the yearly average of local foundation grantmaking benefiting immigrants and refugees in 50 states and the District of Columbia increasing from $226 million in 2012-2016 to $304 million between 2017 and 2018. The yearly average of local funding for the pro-immigrant, pro-refugee movement groups also increased from $42 million to $116 during this same period.

- A sample of 530 of the largest state-based grantmakers in each state [11] and the District of Columbia found that 254 across 49 states (47.9%) gave at least one grant to organizations that service this population in 2017-2018.

- Slightly more than half of the 254 funders (132 across 35 states) in this sample of top local funders also gave at least one grant to movement groups involved in organizing and advocacy.

- At least 50% of this sample of top local funders across 26 states financially supported immigrant and refugee servicing organizations. In standout states Illinois, Massachusetts and Minnesota, a full 90% of their state’s largest local funders dispersed funds to these nonprofits.

- More than a quarter of foundations in our sample (157 funders across 47 states or 30%) matched or exceeded their state’s aggregate share of funding for organizations’ benefitting immigrant and refugee communities.

THE BAD:

- Despite increases, the amount invested in local immigrant and refugee communities in 2017-2018 continues to be disproportionate to the population and the threat, at just 1% (for servicing organizations) and 0.4% (for movement organizing) of all local foundation dollars given out.

- Foundations in most states didn’t even hit these total percentages: In 2017-2018, foundations in less than a third (14) of states met or exceeded the 1% threshold for local funding benefiting immigrants and refugees and foundations in only 8 states matched or exceeded 0.4% of their shares of local funding for pro-immigrant, pro-refugee movement organizing.

- Just 14 foundations in 10 states in our sample of the largest local funders met their state’s current demographic representation threshold by distributing funds at or above the same percentage as foreign-born populations’ share of total population in each state.

- Only 8 states had a majority of their largest local funders match or exceed their state’s giving percentage to immigrant and refugee movement groups.

- A little more than half of foundations (271) in our sample of the largest local funders in all locations didn’t give a dime to nonprofits serving immigrant and refugee populations or to movement groups engaged in pro-immigrant, pro-refugee organizing and advocacy.

LEADING BY (LOCAL) EXAMPLE

Despite the overall need for more state top 10 funders to increase their financial support of immigrant and refugee communities, there is enough evidence to believe that foundations as of 2017-2018 are moving toward being more responsive to foreign-born populations in their states.

Many of the 14 foundations in our sample that matched their state’s share of the foreign-born population also invested in movement groups at shares greater than their state’s total percentage to movement groups. However, 2 grantmakers among this group of 14 stand out for distributing grants to both population serving organizations and movement groups at shares that matched their state’s foreign-born population.

- Rose Community Foundation in Colorado gave out 15.8% of their total funding in 2017-2018 to organizations serving immigrants and refugees and 13.6% to movement groups. This exceeded not only the state’s percentage of foreign-born residents (9.5%), but its 0.4% and 0.2% shares for immigrant and refugee serving organizations and movements. The figures are even more impressive when you consider that from 2012-2016, the foundation only gave those 2 sets of grantees 4.2% and 0.9% respectively.[12]

- In a state with a foreign-born population of 13.1%, the Legal Foundation of Washington has always seemed to have the immigrant and refugee population in its funding strategy. So, some might argue that the increase in their share of funding to foreign-born serving populations and movements wasn’t quite as dramatic as Rose Community Foundation, going from 12.5% in 2012-2016 to 16.2% for both groups in 2017-2018. However, that cynicism ignores not just the foundation’s consistent population and movement financial support over this period, but also this truism: Sometimes the hardest part of the journey is the final stretch before the finish line and finding the internal will to match and exceed funding goals.

It’s important to note that within each state, the difference between shifting the needle and enabling more funds to flow through these community groups often lies within a manageable set of relationships that advocates are working through, but whose efforts may not have yet borne fruit. Still, the issue in many places is not a question of education or even will, but of urgency.

Immigrants and refugees are an integral part of America’s social and economic fabric, as coworkers, neighbors, family members and friends. They are also a key part of our future, as one in every 4 children in the U.S. lives in an immigrant household.

While every funder is different, every foundation in every state can do more to support their immigrant and refugee neighbors. Local grantmakers have an opportunity to provide important leadership – not only in the current crisis, but long-term.

What actions can funders take? Here are 3 practical steps:

1. Make giving match your community, now and for the long-term: Local philanthropic leaders should come together to ensure that their collective giving for immigrants and refugees, at minimum, reflects the demographics of their community. As they do, they should provide rapid flexible support to meet this moment and pledge to integrate such funding into their portfolios over the long-term. While the ultimate target goal may seem ambitious, they should look to find comparative benchmarks that allow them to urgently build on their efforts without lulling colleagues into complacency. Grantmakers Concerned with Immigrants and Refugees (GCIR) has created local “Delivering on the Dream” pooled funds in several cities and states to support immigrants and refugees and can guide foundations to join these existing efforts.

2. Prioritize the pro-immigrant, pro-refugee movement as a crucial partner. When providing these funds, local foundations must prioritize giving to local pro-immigrant, pro-refugee movement groups. In addition to providing crucial services, these groups organize and advocate with the community to challenge the roots of inequality and provide power and protection when systems fail. Don’t know who these groups are in your city or state? Each state profile on this report’s dashboard lists nonprofits working alongside the pro-immigrant, pro-refugee movement serving that state who can serve as resources to aid your work in identifying local grassroots organizations.

3. Wield and share your power to act as an ally: Grants are necessary, but funders can do much more. By meeting directly with local pro-immigrant, pro-refugee movement groups, funders can identify other institutional opportunities to support their neighbors including screening endowments for companies that profit off of detention and deportation, making public statements against raids, racism and xenophobia, and courting immigrants and refugee community members for your board, staff leadership and advisory councils.

While the above steps are doable, concrete ways to move forward, they represent a shift from the way many funders operate. It takes collective leadership, coalition-building and courage to embrace change in order to do the right thing. But now is a critical time to make bold choices.

This work comes in the context of a nation engaged in an ongoing power struggle between 2 visions. One led by movements seeking to create a more equitable, just society for all. The other is led by a status quo pushing hard to maintain hundreds of years of state-sponsored racist, xenophobic, sexist and homophobic systems of exclusion that have built deep inequities into and across institutions that deliver services and distribute power.

It also comes within the backdrop of a pandemic that is revealing just how far leaders and institutions are willing to go to support equity goals and values. While there are signs that local philanthropy is trying to step up to respond to the way that COVID-19 is disproportionately wreaking havoc on communities of color regardless of legal status, initial data shows that funding is still are not reaching the neighborhoods that need it the most.

When NCRP launched our Movement Investment Project in 2019, we noted that philanthropy has an urgent opportunity to support immigrant communities organizing to combat hate and create a better future for all. The progress that has been made is nowhere near proportional to the challenges our immigrant and refugee neighbors, coworkers, caregivers, family and friends confront, especially in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic.

When local foundations invest in immigrants, refugees and movement groups, lives and grant outcomes are better for everyone. The question remains: What will it take for more local funders to seize this current opportunity to act on this urgency?

ENDNOTES

1. Local to local funding refers to funding by grant makers to recipient organizations located in and serving the population of the same state (e.g. an Alabama-based funder giving to an Alabama-based organization). For more information on how we calculated those numbers, visit this brief’s Methodology section

2. In this brief we compare funding for two sets of groups. “Organizations that serve or benefits immigrants and refugees” are non-profits who have received funding to do either directly provide services for or whose work benefits immigrants and refugees, including but not limited to those that are led by those impacted communities. The other set – “the pro-immigrant, pro-refugee movement groups” are primarily advocacy non-profits whose primary function is advancing the movement’s vision of safeguarding basic civil and human rights for families not born in the United States but who seek to thrive here just like anyone else. For more information on defining movement groups, visit this brief’s Methodology section, as well as the first MIP brief, the State of Foundation Funding.

3. In addition to analyzing local philanthropic data in the aggregate, we also examined the largest local funders in each state and D.C. We looked at the largest ten in each state except for California and New York, where we examined the top 20. We expanded the field of examined foundations in these two states to factor in the large size of the state, its foreign-born population and the number of immigrant and refugee servicing non-profits in those areas.

4. Batalova, Jeanne , Brittany Blizzard, and Jessica Bolter. “Frequently Asked Questions: Immigration Enforcement.” Migration Policy Institute. https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/frequently-requested-statistics-immigrants-and-immigration-united-states#Immigration%20Enforcement [Last accessed May 14, 2020]

5. Ibe, Peniel. “Trump’s attacks on the legal immigration system explained.” American Friends Service Committee (AFSC) Blog. https://www.afsc.org/blogs/news-and-commentary/trumps-attacks-legal-immigration-system-explained. [Last accessed May 14, 2020]

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid

8. New American Economy. “Report: Immigration and COVID-19.”New American Economy Research Fund.https://research.newamericaneconomy.org/report/immigration-and-covid-19/ [Last accessed: May 14, 2020]

9. Bier, David J. “Immigrants Aid America During COVID-19 Crisis.” The Cato Institute. https://www.cato.org/blog/immigrants-aid-america-during-covid-19-crisis [Last accessed: May 14, 2020]

10. The data compilations here can be seen visually seen on the interactive data dashboard. Text tables of these compilations are available upon request.

11. See End Note 3.

12. In April 2019, The Latino Community Foundation of Colorado (LCFC), which had operated as an initiative of Rose Community Foundation for 11 years, became a separate, independent 501(c)(3) organization. Because 2019 funding data is not publicly available, this report does not address the impact this shift may have had on state and local rankings and/or the Rose Community Foundation’s share of funding in particular.