“…What infrastructure do I see now? A region with a shared history that connects people – the history of slavery, oppression and rebellion. There’s one thing people in Mississippi can know about people in Alabama without having to even talk to them, and that’s ‘You survived and we survived. We’re both still here because we both have survival methods.’

“And it’s not something that someone from another part of the country would see, I don’t think. Somewhere else they might see someone and say ‘Oh, you’re here.’ But when I see someone in the South it’s a different acknowledgement. It’s ‘We’re still here.’ It’s a collective ‘We.’”

INTRODUCTION

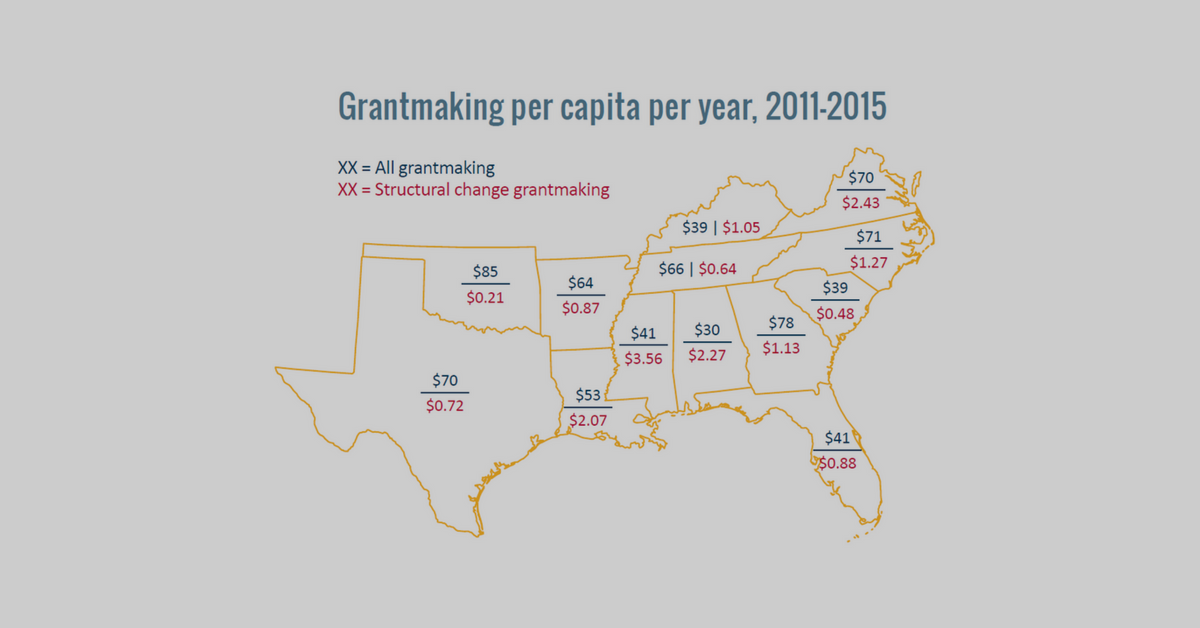

Between 2011 and 2015, foundations nationwide invested 56 cents per person in the South for every dollar per person they invested nationally. And they provided 30 cents per person for structural change work in the South for every dollar per person nationally. It is hard for Southern leaders, especially those at the vanguard of social change work in their communities, to reconcile the reality of a region full of innovative and effective social change networks with the long-standing dearth of resources to support their work.The soil for growing exciting solutions to national problems is deep and fertile in the South; the seeds are present, and foundation staff haven’t turned on the water. It’s time to open the spigot.

Because the South is and has often been the proving ground for some of the nation’s most regressive public policies and rhetoric, choosing not to invest in Southern structural change work puts marginalized people across the country in harm’s way. Wages are too low to support working families in the Midwest because of anti-labor legislation exported from Southern states. Cities and states in the Southwest model their systemic harassment of immigrants on policies and practices pushed by a powerful minority of Southern elected officials. The road to a more equitable future nationally runs through the South.

Southern leadership understands the twists and turns that lie on the road ahead. These leaders understand how we, as a nation, can find our way to a better, more just future because they’ve won a better future for themselves and their families again and again against stacked odds. Today’s movements for justice and equity are putting down deep roots at the intersections of gender, race, class, sexual identity and immigration status across the South.

Southern organizers understand how to operate in an environment where money for their work can be scarce, but where reciprocal communal support has sustained their communities for centuries. They also understand how to move safely and strategically in a region where the threat of economic, social and even physical retribution is still real. They are equipped to teach and lead their allies across the country in a vision that can win against forces of division, obfuscation and oppression. Southern organizations and the networks they comprise have all of this. What they don’t have so much of is philanthropic support to turn vision and skill into larger-scale change.

READ RELATED SECTIONS

THE BOTTOM LINE

A NEW WAY TO DO GRANTMAKING IN THE SOUTH

HOW TO MOVE FORWARD

CONCLUSION

What do we mean by structural change grantmaking?

Throughout this report and others in the As the South Grows series, we used the phrase “structural change grantmaking” to describe the kind of philanthropy Southern communities need. There is no rigid definition of structural change grantmaking; context matters, and our understanding of structural change ought to deepen and adapt with time. Here is some of what that phrase means to NCRP and GSP.

When we say “structural change,” we mean transforming the unjust structures in our society that collectively hold us back: laws, norms and biases whose complex effects have built up over time. Structures and systems themselves are not inherently unjust; many of them are unjust because the power to make the rules has been entrenched in the hands of select groups of people. Structural biases and disadvantages don’t have to be conscious or intentional to be unjust.

Structural change grantmaking prioritizes equitable outcomes for marginalized communities as its end goal. It improves the quality of life and increases the power of marginalized communities such as people of color, immigrants, poor people, LGBTQ people and other groups at a disadvantage in our society. These groups of people experience poverty, violence, poor health and other challenges at disproportionate rates not because of bad luck but as the result of active choices people in power have made over time.

Often those active choices have been informed by racism, sexism, xenophobia and anti-LGBTQ bias. Putting marginalized communities at the center of a structural change grantmaking strategy is not only the just thing to do, it is the most effective thing to do. When barriers to prosperity, health and safety are removed for these groups of people, whole communities and, therefore, society are better off. This kind of grantmaking strategy requires funders to be thoughtful and intentional about making grants in all the places marginalized people live, including in rural areas as well as cities.

Structural change grantmaking increases marginalized communities’ power to allocate public resources, to exercise their constitutional rights, to tell their story and be listened to, and to knock down barriers to opportunity for their communities and others. The most basic form of philanthropy is charity, and structural change grantmaking builds on that foundation by addressing the fundamental conditions that make charity necessary.

Structural change grantmaking is accountable to and informed by marginalized communities, including the grant award decision-making process. When done well, marginalized communities can use these grant dollars for their own self-determination, rather than fitting their work into someone else’s idea of what their priorities should be.

Structural change grantmaking is about trusting communities of color, immigrants, women, LGBTQ people and other marginalized communities to know what they need, and to reduce the barriers that prevent these communities from achieving the justice they seek. It’s about recognizing how power and privilege affects every aspect of the grantmaking process and consciously choosing to partner with these communities to acknowledge and subvert those dynamics.

This report and others in the As the South Grows series include the authors’ analysis of Foundation Center grants data. The structural change grantmaking the data describe includes codes like policy, advocacy and systems reform; community organizing; democracy; and human rights. When possible, the data are disaggregated along other factors of identity that impact power and resources like race, ethnicity, class, gender, sexual identity and immigration status.

For more on structural change grantmaking, see:

THE BOTTOM LINE

In the two years that the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy (NCRP) and Grantmakers for Southern Progress (GSP) have been working on an initiative to drive more philanthropic resources to structural change work in the U.S. South, we’ve conducted more than 150 interviews with philanthropic and nonprofit professionals working there (including at national foundations). From grassroots Southern leaders we’ve heard frustration and worry, but more than anything we’ve heard about the resilience and knowledge that exists in the Southern nonprofit ecosystem. From foundation staff, we have heard about the deep interest and excitement that comes from learning from and listening to the most affected Southern leaders.

But interest, concern and abstraction within the philanthropic sector will never be enough to make real progress in the South. And the country writ large will be prepared to confront the defining issues of this generation – changing climate, increased global migration and transition to a new economy – only after a renewed movement for democracy and justice in the South.

“…Folks get disheartened and say ‘We’ve been fighting for this thing for three years and we haven’t won yet.’ How many hundreds of years did it take to get to get slavery abolished? It takes time, and deep investment is necessary. And we know in our hearts that when that deep investment is made, that’s when the South shifts and starts a domino effect. The nation will feel the impacts of that shift.”

The bottom line remains: Southern and national grantmakers with an interest in helping to build power, wealth and resilience in the South still need actionable guidance to help make those investments a reality. Philanthropic leadership is still too often tripped up by stale stories about Southern intransigence or by a false choice between charity and justice.

The framework that follows provides a roadmap to overcome those barriers so that Southern leadership can start taking full advantage of philanthropic resources and turn soil and seeds into a sustainable grassroots ecosystem.

In On Fertile Soil, we spotlighted nonprofit leaders in the cradle of the Civil Rights Movement to refute a frequent philanthropic justification for lack of Southern grantmaking: There is not enough capacity in the South. The capacity for innovative, cross-issue and cross-constituency movement-building does exist across the South – including the rural South – if foundation staff look for it in the right places and with the right lens. Often that work is being done by people of color and especially by women of color, who bear the brunt of structural inequity in the region.

READ AS THE SOUTH GROWS: ON FERTILE SOIL

In Strong Roots, we explored the connection between community-driven economic development and equity in the South, with a particular focus on two communities historically kept on the margins of the region geographically and economically. In the Lowcountry of South Carolina and Coal Country of Eastern Kentucky, and in places like it across the region, Southern leaders are pioneering strategies to lift communities out of generational poverty, and along the way they’re building powerful bases for longer-term policy-change work. Foundations interested in building community wealth must acknowledge the potential of equity-focused, community-led economic development strategies in the South.

READ AS THE SOUTH GROWS: STRONG ROOTS

In Weathering the Storm, we highlighted the enhanced threat to Southern people and Southern land posed by climate change and provided examples of grassroots Southern nonprofit networks waging a fight on multiple fronts to ensure the physical and spiritual survival of their communities. The economic and social devastation of sea level rise and worsening tropical storms is already a reality in places like Eastern North Carolina and Coastal Louisiana. Foundations across the country will soon need to understand how climate, ecology, economics and politics intersect with racism and poverty. Southern grassroots leaders have already developed a sharp analysis of these issues – an analysis they rely on to mobilize Southern communities to build a more resilient future.

READ AS THE SOUTH GROWS: WEATHERING THE STORM

And in Bearing Fruit, we traveled to sprawling, booming Metro Atlanta and amplified the work of grassroots and grasstops power-building organizations in the region. Like other growing Sunbelt cities, Atlanta’s reputation for forward-thinking civic and business leadership masks a more complicated reality where gentrification, displacement and criminalization of marginalized communities are too common. A vibrant activism ecosystem has met these challenges, but that ecosystem’s impact won’t reach its full potential without the resources to build out robust, whole organizations with the time and money to collaborate and expand their reach into suburban and rural areas around Atlanta.

READ AS THE SOUTH GROWS: BEARING FRUIT

A new way to do grantmaking in the South

After two years of research and coalition-building, 150 interviews, four Southern focus groups and countless conversations with foundation staff, we believe that, in order for structural change grantmaking in and to the South to increase, the way grantmaking is done in the South will have to fundamentally change. Simply tweaking the frequency or dollar amounts of present grantmaking won‘t bring the change necessary. The South is at a disadvantage in the current dominant grantmaking paradigm of most foundations, and that paradigm has to change in order for grantmaking disparities in the South to change.

More specifically, the way foundations justify making a grant must change to break down the structural disadvantage that Southern equity work is subjected to in that process. The philanthropic sector’s grantmaking process must root out values and practices that have deprived Southern grassroots social change networks of resources.

To do all these, grantmakers need to take the following three steps:

- Reckon with shared history.

- Weigh the stakes of the status quo and risking our privilege.

- Recognize and honor capacity.

This roadmap points toward the ultimate long-term goal of repairing broken relationships – between and within Southern communities, between Southerners and the philanthropic sector, and within the philanthropic sector itself. Repairing broken relationships will require making amends – putting together what’s broken means making it whole again physically, spiritually and financially. And that reparative process will mean redistributing money and power within the philanthropic sector and from the philanthropic sector to Southern communities.

RECKON WITH SHARED HISTORY

Likewise, good structural change grantmaking in the South requires an understanding of the complicated history of the region as well as an understanding of the region’s role in our nation’s history. Understanding that history is difficult because it is complex and includes as much tragedy as triumph (not unlike the country’s history). But glossing over that history in favor of a focus on the individual or on the region’s present challenges isolated from their deep roots makes for ineffective philanthropy. Too often, foundation staff and donors misunderstand or choose not to try to understand the South’s history, and their philanthropy suffers for it.

Often well-meaning foundation staff and donors intend to, for example:

- Nurture or reinforce a culture of self-reliance and sustainability without continued public support or charity.

- Take a race- and ethnicity-neutral approach to grantmaking to avoid favoring one community or group over others.

- Avoid hot-button controversial issues – such as racism, sexism and homophobia – in favor of universal charitable giving strategies for the betterment of all.

- Respect the specificity and complexity of Southern history and culture, especially with regard to race, gender and politics; avoid being perceived as a carpetbagger.

- Avoid “stirring the pot” by funding work that may generate backlash from civic and business leadership and jeopardize the foundation’s reputation for being “above the fray.”

And the impacts of those choices are to, for example:

- Allow history to go unexamined and its impact on the future unchallenged.

- Let past wrongs go unrighted and mistake ongoing generational poverty and disenfranchisement for an individual responsibility instead of a shared one.

- Let those who benefit from the way things are now dictate the story including what’s off limits for conversation and what is too dangerous to be honest about.

- Undervalue the role race and ethnicity have played and continue to play in who has access to resources and who does not and who has a voice in the debate and who does not.

- Overvalue the appearance of foundation neutrality, which is not truly possible, nor is it the most effective role for an institution dedicated to the public good.

- Fail to appreciate how the past, present and future fate of Southern communities links with the rest of the country and world.

- Obscure the role national institutions have played in extracting wealth and power from the South.

- Allow those invested in the status quo to drive a wedge between Southerners and non-Southerners and put cross-region collaboration out of bounds.

Instead, foundation staff and donors should, for example:

- Embrace the discomfort. Thorny problems like generational poverty persist in part because we – all of us – are on some level comfortable enough with their persistence. It follows that tackling these challenges with deep historical roots will be uncomfortable, even painful for some. Don’t let that deter your grantmaking.

- Disaggregate your data. Break down quantitative and qualitative data by race, ethnicity, gender, class, sexual orientation and other factors that influence access to opportunity. Ask which communities are disproportionately affected by issues and who stands to benefit from the status quo. Use this powerful data to inform grantmaking decisions. Consider the ways universal strategies can be targeted to those who are already at a disadvantage.

- Strive for a balance between linked fate and individual and local autonomy. Grantmaking in the South can and should respect the self-determination of Southern communities and the dignity of each individual as well as reckon with the history of outside interference in Southern communities and the backlash that came with it. But South and North, South and the rest of the country, South and the globe have always and will always be interdependent. Design approaches to relationship-building and grantmaking that hold that tension well and strive for mutually accountable and beneficial relationships between funder and grantee.

- Be open and honest about Southern history’s role in the present and keep the conversation going. The history of racism, sexism, extraction and exploitation in the South is complicated, and it has a big impact on the present and future. Ask questions of folks in communities who have unrivaled – often personal – knowledge of that history, and don’t shut down the conversation when it gets hard. Southern structural change grantmaking can only be effective if it grapples with that history sincerely. Perfect understanding should not be the goal; listening, learning and regular re-evaluation of grantmaking strategies should be.

LEARN MORE:

AS THE SOUTH GROWS

ASSESS THE STAKES OF CAUTION OR INACTION AND RISK YOUR PRIVILEGE

Good philanthropy relies on a solid understanding of the facts on the ground, and a commitment to meeting the needs of those who have the least wealth and power in our society. But when it comes to philanthropy in the South, foundation staff often get bogged down in the learning phase of grantmaking or they take a cautious approach that funds only direct services instead of long-term change.

Foundations not based in the South are right to prioritize relationship-building and learning first, and Southern foundations are often faced with urgent community needs where philanthropy can make a difference. But caution about investing in Southern structural change work without the right information has a cost.

Additionally, pessimism about the potential for changing the root causes of community challenges shouldn’t mean that funding Southern structural change is off the table. At the root of these mindsets is the belief that the status quo is the best we can hope for. Action to change the status quo would require risk, the thinking goes, and that risk isn’t worth it if this is as good as it gets. But grassroots Southern activists know that change for the better is possible.

Often well-meaning foundation staff and donors intend to, for example:

- Get smart: Spend time and thought learning all they can about Southern structural change work before they invest any resources.

- Go slow: Avoid backlash by investing only in strategies that won’t ruffle too many feathers – real change, after all, happens slow and steady.

- Mitigate risk: Identify all the possible outcomes of a grantmaking strategies in the South, then choose the best one.

- Fund urgent needs only: Tackle issues that have linear, short-term, “fundable” solutions – like a free clinic or a food bank – instead of controversial systemic challenges.

- Prioritize direct service funding, especially in Southern communities where many basic needs are not currently being met.

- Protect your credibility and influence at your institution by finding safe ways to channel resources to Southern structural change work in a way foundation leadership can accept – or in ways they won’t recognize as a departure from the status quo.

And the impacts of those choices are to, for example:

- Extract the time and expertise of Southern communities without an investment to replace, or even expand, those resources.

- Pass up the opportunity to change the conditions that lead to entrenched poverty, environmental degradation and other forms of marginalization.

- Assume that slow and steady is the best approach to long-term change when grantee organizations may disagree.

- Exacerbate the inequity of grantmaking between the South and the rest of the country and within the South for marginalized communities.

- Overvalue your own credibility and career considerations instead of putting mission first.

Instead, foundation staff and donors should, for example:

- Understand that inaction has a cost. Find ways to quantify that cost. There’s a time and a place for a slow and deliberate approach to big changes; let your grantee partners lead the way, and you’ll now when that time is. Don’t assume the gradual approach is the best one, and remember that the status quo is costly, too. Knowledge is powerful, and foundations are right to want to gather information. But there will always be more questions to ask and more data to collect. At some point, action becomes necessary. Race, gender and class inequity is costly in financial and social capital, so philanthropic deliberation and slow-walking has a big price tag for communities – and for us all.

- Imagine how things could be different. Believe in Southerners’ vision for the future – like applying a bandage to a gushing wound, funding only direct services isn’t going to solve the problems Southern communities face in any long-term way. It accepts a false choice about philanthropy and charity that isn’t necessary, and it reinforces decades of disparity in grantmaking in the South. National foundations that are committed to equity should consider adding a regional equity lens to their grantmaking. And Southern structural change grantmaking can and should employ a multimodal funding strategy that helps meet human needs and builds the power of communities to address the root causes of inequity. In fact, structural change work in the South often grows organically out of organizations dedicated to meeting needs because they are well-positioned to envision how systems can be better designed to be more just and equitable. Often their vision is not linear, but that need not make it unfundable or unmeasurable.

- Understand the privilege that comes with your position and your identity. Find ways to quantify privilege that comes from your race, gender, class and other identities, and deploy it strategically to tip the scales in favor of action. Safe, discreet and non-disruptive grantmaking has a value, too, but too often the people it protects are those with the most wealth and power – not the least. Your credibility and influence at your foundation is a powerful tool – use it to drive change and share with marginalized Southern communities who don’t have the influence and access you do. Think of your privilege – the reputational capital and access that come with your position and your identity – as an asset to be invested in grantees and communities who can turn it into change opportunities.*

*Find more resources about understanding and using your philanthropic sector privilege in NCRP’s Power Moves: Your essential philanthropy assessment guide for equity and justice.

RECOGNIZE AND HONOR CAPACITY

Most thoughtful grantmakers look for high-capacity organizations and leadership that will transform their philanthropic capital into real-world impact on the issues they care about. That’s a reasonable and often effective way to make grantmaking decisions, but capacity is difficult to define objectively. And that makes it susceptible to implicit biases, which are at the root of much of the Southern structural-change grantmaking disparities.

Foundation staff mean well when they place a high value on grantee capacity, but in practice the impact of the sector’s dominant working definitions of capacity – many of which are implicit – has been to deprive the South of needed resources and the nation of much-needed Southern leadership.

Often well-meaning foundation staff and donors intend to, for example:

- Invest in organizational leadership with a proven track record of success.

- Invest in organizations with the familiar signs of capacity, e.g., staff with advanced degrees, polished grant proposals and external validation from other foundations or established civic leadership.

- Seed new nonprofit infrastructure in Southern communities where it appears to be missing.

- Mitigate risk by investing in stable organizations – organizations where other foundations have already invested or in organizations with a healthy balance sheet.

- Replicate successful nonprofit ecosystems from other places by building something new or by funding big organizational development changes at existing nonprofits.

The impacts of those choices are to, for example:

- Perpetuate grantmaking inequities that may be based in implicit biases about region, race, gender, class and other factors.

- Reinforce inequitable access to philanthropy that may have been granted by gatekeepers who don’t value a structural change strategy.

- Mistake privilege for the capacity to get the work done and put a high value – in real dollars and cents – on grant-seeking skills instead of mission-related skills.

- Displace or disrupt existing infrastructure, which may not be familiar or recognizable to inexperienced eyes or which may be hard to find by design.

- Underestimate and undervalue the risk to grassroots leaders who often work without fair compensation, without benefits or under threat of retribution.

- Underestimate and undervalue the risk tolerance potential of philanthropic capital.

- Import a nonprofit infrastructure that is not adapted to succeed specifically in the South.

Instead, foundation staff and donors should, for example:

- Spend time and resources identifying existing infrastructure. This means being present in communities and listening with a willingness to be challenged by what you hear. It also means building relationships with local leadership – especially leadership from marginalized communities – and putting some skin in the game up front. In other words, make it clear that you’re not just there to learn, observe and extract information from the community; you’re there to partner and invest.

- Change your expectations about what signs of nonprofit capacity look like. Adapt those expectations to place. Consider what signs of capacity might be in a region without sustained philanthropic investment, without high-quality universal education and without a progressive social safety net. Consider how signs of capacity may be hidden in a region with a history of economic, social and even physical retribution for challenging the status quo. In what way might capacity announce itself in a region with a vibrant faith-organizing ecosystem, with a long history of complex resistance mechanisms – small- and large-scale – and with a high cultural value placed on mutual aid and communal life?

- Trust that the people closest to injustice, inequity and the work required to correct them are best at that work. Don’t just find and fund those people: hire them. Southern grassroots leadership understands how the work will get done, and this leadership is skilled at allocating scarce resources to make sure the work happens, too.

- Measure, value and invest in new signs of capacity – reciprocal relationships, resistance (not always progress) and resilience. We measure what we care most about, and we’ll invest where we find value. Measure each community’s investment of time and in-kind resources in building relationships and in resisting harmful changes. Put a high value on opportunities for you, the grantmaker, to be challenged and improve your grantmaking practice. Invest in whole people – looking beyond their roles in an organization or status as leaders – and embrace the complexities and diversity of each leader’s gifts and needs.

RELATED READING:

AS THE SOUTH GROWS: ON FERTILE SOIL

AS THE SOUTH GROWS: STRONG ROOTS

AS THE SOUTH GROWS: WEATHERING THE STORM

AS THE SOUTH GROWS: BEARING FRUIT

How to move forward

“…Largely, funders want to see immediate or short-term change or something concrete like a policy passed. Until this country has a truth and reconciliation process, it can’t be just about policies. And that work has to be relational. That work is long-haul work and necessary work.”

Repair broken relationships and redistribute money and power.

High-capacity Southern social change networks exist across the region. And change for the better is possible. And yet, as the funding data show, the resources to drive that change have not found their way into Southern hands. Ultimately, our conversations with grassroots Southern activists, Southern family and community foundation staff and large national foundation staff point to a simple factor behind that dearth of funding that is nonetheless exceptionally difficult to change: trust.

Foundation staff and trustees – national and Southern – do not trust Southern leadership, especially when that leadership is by women – especially Black women – people of color, poor people, LGBTQ people and immigrants. They don’t trust that it is possible to move the needle on stubborn challenges in the South, and they don’t trust that a dollar spent on amplifying the voices of those with the least wealth and power in the South is a smart way to better the day-to-day living conditions in Southern communities. Funder staff and trustees do not trust that Southern grassroots networks understand how to use scarce resources effectively to win big victories. They don’t trust Southern leadership enough to trust them when they say they need time, space and resources to heal before they return to the frontlines.

Likewise, many grassroots leaders in the South do not trust philanthropy, even when foundation staff and donors have the best intent. Philanthropic resources can be a powerful tool for long-term change; in the South (and in other historically under-invested places), however, many community organizations have written off philanthropy. Some have been burned by foundation staff who promise the world and do not deliver; some have been frustrated for too long by foundation staff’s inability to work effectively in the region. Broken relationships and mistrust are left in the wake of decades of philanthropic misadventures.

“…Some people feel more comfortable funding a coalition but even when you fund a coalition or a hub you need to give that hub a $1,000,000 grant just to be able to [perform their basic coalition function].

“[The South has] been under-resourced for so long that it’s going to take reparation [to make a difference]. Black people have been held back for so long that nothing short of total redistribution and reparation is going to start to change that.”

The most promising way to overcome this lack of trust between philanthropy and grassroots Southern leadership is to build relationships. And to do this, grantmakers need to:

- Find out what’s broken. Find out how your institution has or has not interacted with marginalized communities in the South in the past. What relationship does the wealth donated to the foundation have to those communities? Questions like these are especially salient for foundation trustees and donors to begin a conversation around. What grantmaking strategies has your institution deployed in the South before? If your institution has never funded structural change work in the South, ask “Why not?” Explore the ways your institution may have made mistakes in Southern communities in the past. Ask yourself and your colleagues how you all can correct those mistakes.

- Put relationship-building front and center in your grantmaking strategy. Don’t get too bogged down in trying to have all the data. Developing trust and relationships will lead you to the right people and information. Be ready to make the time investment into building relationships, spending time in the South and in towns that are not as easily accessible from a large city.

- Shift power and resources to Southern leadership. Trusting, lasting relationships between philanthropy and the communities it serves can go beyond the charitable haves and have-nots paradigm of the past. In the South, where reciprocity and mutual aid are built into communal DNA, foundations and donors have an opportunity to learn with grantee partners and to learn how to shift their power and resources to communities that can use that power and resources to make big changes. Measuring what’s broken in philanthropy’s past engagement with Southern communities and then building relationships within those communities ought to lead to repair.

8 Things you can do right now to jump-start your high-impact grantmaking in the South

1. Re-evaluate your institution’s administrative processes and requirements to allow for different definitions of capacity, success and risk better suited to the Southern grassroots context.

Find ways to measure community assets like grassroots leadership; in-kind support for grassroots organizations from churches, schools and individuals; long-term relationships between leaders within and across communities; demonstrated resistance capacity.

Adapt institutional polices that prohibit providing a certain percentage share of a prospective grantee’s operating budget to better fit the Southern context. Decades of philanthropic under-investment will not be overcome until those policies bend to meet Southern organizations where they are.

2. Reach out to those foundations in the South already funding structural change work.

Ask them for advice. The learning community hosted and facilitated by Grantmakers for Southern Progress is a good venue to begin building these relationships with Southern funders. GSP’s convenings, webinars and in-region learning tours will connect foundations to Southern peers who are doing innovative, high-impact structural change work.

Examples of Exemplary Southern Funders:

- Foundation for Louisiana

- Greater New Orleans Foundation

- Baptist Community Ministries (LA)

- Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation (AR)

- Southern Partners Fund (GA)

- Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation (NC)

- Kate B. Reynolds Charitable Trust (NC)

- Smith Reynolds Foundation (NC)

- Appalachian Community Fund (TN)

- Contigo Fund (FL)

3. Invest in grassroots civic engagement infrastructure now.

This year, grassroots organizations across the South (and across the country) will mobilize to register people to vote and to ensure as many people who are eligible to vote do so in primary and general elections that will send elected officials to statehouses and the U.S. Capitol in the fall.

In the South, where philanthropic resources have historically been thin on the ground, many organizations whose primary, explicit mission is not necessary civic engagement will ramp up civic engagement programs in 2018 because they understand that, in order to continue providing services to meet urgent needs, marginalized communities need accountable and visionary representation at the local, state and federal levels.

Similarly, beginning in 2018 and continuing into the coming years, Southern organizations will begin building programs to ensure the 2020 census is fair and accurate. Again, even organizations whose mission is not directly related to the census recognize that how people in their communities are counted by the government has a direct and lasting impact on their work. Grantmakers for Southern Progress has adopted Census and Redistricting as a programmatic priority for the coming years and is collaborating with Southern and national funders to organize a Southern Regional Census and Redistricting conference in June of 2018. The objective of this conference is to discuss and begin to coordinate philanthropic activities, strategies, and goals for Southern states for the 2020 Census and the redistricting process in 2021.

These mass mobilizations, including both institutionalized nonprofits and other less formal groups, will provide myriad opportunities for foundations that are new to Southern structural change grantmaking to make bold investments and then learn quickly from those investments. If foundations and donors are willing to rethink risk and get money to the grassroots in the South quickly and nimbly, they can evaluate and iterate that grantmaking in the coming years.

Southern civic engagement funding is needed, and it is an opportunity for philanthropy to begin practicing a new way of doing structural change grantmaking in the South. Do not pass up that opportunity. And do not squander the impact of your investment by pulling out after the election or after the census is complete. Your support will be necessary to protect hard-fought victories and to continue building on infrastructure for long-term power.

4. Take a risk.

Put some skin in the game and be ready to learn from the outcome. Give more multi-year general operating support to your Southern grantees and consider adapting institutional requirements around budget minimums and grant support maximums to better fit the Southern context. Decades of disinvestment call for flexible, committed grantmaking now.

5. Join Grantmakers for Southern Progress.

Build perspective, knowledge, strategy and collaborative relationships for structural change grantmaking in the South.

6. Hire Southerners – especially Southerners with backgrounds in grassroots organizing and with a race- and gender-equity lens.

Being in deep, long-term relationship with Southern grassroots organizations and with Southern structural change funders will connect you to leadership pipelines.

7. Deepen your capacity to integrate a racial and gender equity lens into your grantmaking that is in the context of the South.

In 2019, GSP will launch a Racial and Gender Equity Leadership program that will train southern and national philanthropic leaders to understand the intersection of race and gender in the South so that they can address the root causes of the inequities that impact the people and communities their respective foundations seek to serve.

8. If you’re already moving money to Southern-led structural change work, organize your philanthropic peers to do the same.

The co-learning and co-strategizing space GSP holds in the sector is a great place to find peer support for playing this philanthro-organizing role in the broader sector. Seek out others in GSP’s circles who are already successfully moving their institution and others toward greater investment in Southern structural change work and ask them for advice. The organizing tip-sheet is a good place to start, but peer relationships like those facilitated by GSP are the best way to learn.

Conclusion

Old money doesn’t die. The billions of dollars that sit in foundation bank accounts in New York, Atlanta and in towns and cities across the South can be traced back to extractive and exploitative relationships that have dominated the nation’s economic history – and have a special place in Southern history in particular.

Weighing the cost inflicted on Southern communities can seem overwhelming. The individual and communal wounds left from the displacement and genocide of Native people, the enslavement of African-Americans, violence against women and LGBTQ people, and the demonization and exploitation of immigrants in the region run deep – and they are daunting to face.

The problem of where to start measuring that cost and how to quantify it in a present that may seem far removed from the country’s slave economy origins can seem insurmountable. But the South is not exceptional in its violent past. The nation’s prosperity and all who benefit from it share responsibility. And the South’s past (and present and future) is much more than the legacy of violence done to marginalized people. To believe otherwise is to embrace the founding racist myth of our democracy and deny Black, Brown, queer and immigrant Southerners their agency. Embarking on an honest and patient conversation within the philanthropic sector about shared culpability in Southern inequity is the only way to begin healing the relationship between those who have the resources to finance change for the better and those who have the know-how to make it happen.

Changing the way grantmaking is done in the South to drive more philanthropic resources to structural change work will not be easy, but it will be hard work that any foundation can be proud of. And an earnest attempt to make right past wrongs could be the beginning of a new way to do philanthropy across the country. To be sure, many individual philanthropists and foundations already use a reparative model when they give back. Foundations and donors working in the South should not assume such a model for grantmaking is not possible. In fact, why shouldn’t the region that gave the country one of its broadest and most successful mass movements be the laboratory for new, more effective and more just ways to do philanthropy?

The old maxim is still true: As the South goes, so goes the nation. The South’s fraught history has nurtured a social change ecosystem whose roots run deep, especially in communities who have most often borne the brunt of injustice in the region. Ironically, decades without significant philanthropic investments have collided with the region’s particular communal culture to create an ecosystem where organizing marginalized people across gender, class, race and other identities is the norm, not an exception. The nonprofit sector writ large – philanthropy and grantee organizations – have much to learn from their Southern peers on this front. And the road to more equitable outcomes for women, people of color, low-income people and other marginalized groups nationally runs through the South.

The South is home to inspiring, effective examples of strategies that have been pushing back against stark inequities for generations. If the philanthropic sector does invest in the work of these networks of high-capacity organizations to strive toward greater equity in the region, then the nation will reap the results.

Much has been taken from Southern communities over the centuries since colonization, but the region still has much to give the country – in terms of leadership and a vision for a new way to live together in a beloved community. Philanthropy has the power and resources to match the South’s contribution, if leaders in the sector can develop the skills and the political will to make that contribution real and effective.

The next decade will be a watershed for the country: Will we choose to repair deep, widespread wounds and fend off an existential threat to our democracy? If we do, that reparative process will find capable leadership in the South.

NCRP and GSP are ready and eager to help any foundation or donor get started. But, more to the point, Southern grassroots leadership is ready, too. Seek that leadership out, and you’ll find partners who can turn your philanthropic resources into another movement moment in the history of their communities and the whole nation.

BONUS

Eight tips for organizing in philanthropy

We’ve said that funders need to think about themselves as organizers. What does that mean in the world of philanthropy? No matter how you’re trying to move philanthropy to support Southern-led justice and equity, here are eight tips to get started.

1. Remember why action is important.

Think about the stakes: The broken relationships between philanthropy and Southern communities have damaging consequences that hold the South and the country back. Consider what will happen if you don’t take risks to support the Southern-led, equity-focused organizing it will take to change that. Now flip this thought on its head: Imagine the great things that can happen if you do take risks.

2. Map out your network.

Everyone is part of a network. Whether you examine your own funding institution or your philanthropic peers, consider: Who has power to change the status quo toward Southern-led equity and justice? Maybe this power comes from one’s ability to make grants or from one’s reputation or connections outside the institution. Then consider: Who has influence over them? Finally, ask: Where do I fit in? What influence do I have? You have more power than you think. This is an especially good exercise to do with people you trust.

3. Think big.

Make a list of all the things that are currently in your control. Then, make a list of all the things you could ask others to do, no matter how unlikely it seems that they’d say yes. Get creative.

4. Decide where you’ll start.

Take a look at your list and ask yourself: Is this idea strategic, given the thinking about power I’ve already done? Is this idea aligned with my values and the values we’ve discussed to promote equity and justice in the South? Is this an idea I can work on now?* Circle ideas where the answers to all three questions are YES. That’s where you’ll begin. When in doubt, ask people with a greater lived experience and understanding of racial, gender and class injustice than you do, especially if they’re grantees and activists on the ground. Consider compensating them for their time.

5. Make specific, time-limited asks.

Whomever you ask in philanthropy to take action – whether it’s a trustee, the executive director of a peer foundation, the head of an affinity group or staff at a donor network – ask that person to do a specific thing by a specific time. Speak to people’s self-interests and why they would be good at doing that thing. You’re providing an opportunity that helps people meet their goals.

6. Follow up.

Once people promise they will do something by a certain date, check-in with them. Remind them if they forget. If they don’t follow through, ask why. Once this person does follow through, say thanks! That accountability makes all the difference.

7. Be willing to fail.

Reflect on your work and celebrate small wins. Expect that you will make mistakes and that you may be criticized. Be prepared to recognize mistakes when you make them; be humble and embrace vulnerability. Try again based on what you’ve learned.

8. Do it again.

Take the next step and keep going. Over time, you’ll build a network of people who can take action with you. This is how things change. Philanthropy must change, too.

*George W. Wilkinson, Strategic Planning in the Voluntary Sector, 1986, James R. Gardner, Robert Rachlin and H.W. Allen Sweeny (Ed.), Handbook of Strategic Planning, New York: John Wiley and Sons.

But what if I’m a…

Depending on your position in philanthropy, you may face unique challenges when trying to organize your colleagues and peers to invest in Southern-led equity and justice. But when viewed as opportunities, these challenges also offer advantages you can use to adopt the recommendations in this report.

Some of the challenges we face in changing philanthropy’s norms and practices stem from lack of capacity. Others require a higher level of risk or navigating limited power within institutions. You can choose to be a passive agent of change. Or, by taking risks, recognizing that you have some power and focusing on what you can do in service of what is right, you can be an active change agent. Chances are your peers in other philanthropic organizations are facing similar challenges. Learning from those who have already challenged philanthropy to be more just, equitable and community-driven can help inform your work.

Actions you can take today

Looking for a way to get started? Here are five actions you can do now to begin encouraging philanthropy to change relationship with Southerners building a brighter, more just future:

• Become a member of Grantmakers for Southern Progress and NCRP.

• Share this report and the four prior reports via email, Twitter, Facebook and word of mouth.

• Share an anecdote or a story that we can use to lift up one or more recommendations in this series.

• Write an article, op-ed or blog post that encourages your funding peers to adopt the recommendations in this series.

• Host a conversation to educate and encourage your institution or with peers to adopt the recommendations in this series.

Appendix

Header photo by praline3001. Used under Creative Commons license. Nottoway Plantation, built 1859 in White Castle, Louisiana, is open today as a luxury resort.