As we race toward a general election, nonprofit groups conducting voter registration and mobilization – often referred to as nonpartisan third-party voter registration organizations (3PVRO) – are facing costly new obstacles that threaten to disenfranchise voters and drive down political participation. Nationally, a whopping 57% of the U.S. population live in states across the political spectrum that have passed restrictive voter registration laws to inhibit the work of local civic engagement organizations like Florida Rising, Florida Immigrant Coalition (FLIC), Virginia Organizing or Latino Community Fund.

The Brennan Center for Justice reported that in 2023, 14 states enacted 17 laws that made it harder for eligible Americans to register, stay on the voter rolls or vote (including by restricting 3PVRO efforts), while six states had enacted seven election interference laws. Between January and May 2024, six states enacted seven new restrictive voting laws and one state enacted a new election interference law.

Intro

Obstacles to Building a Multiracial Democracy

The Impact of Restrictions on Groups & for Voters

Philanthropy’s Obligation is Clear

Endnotes

Authors

Laws like Florida’s S.B.7050 include fines of $250,000 per year per organization for infractions like returning a voter registration form a single day after the legally mandated submission window of 10 days. Laws modeled after Florida’s – like Alabama’s S.B.1 – would also increase or impose new penalties on volunteers or workers who assist voters during an election, putting some actions in the same felony category as first-degree manslaughter and second-degree rape.1

While some of the more outrageous parts of these laws are temporarily delayed due to grassroots legal efforts, the parts allowed to take effect are already making an impact. According to NPR, after Florida’s new law restricting voter registration efforts went into effect, incoming registrations through drives fell by 95% compared to the same period four years ago.

The cost of both opposing these rules in court and complying with byzantine administrative rules like these is making an already expensive process even more prohibitive. More importantly, our civic institutions cannot function – let alone thrive – if democratic participation is challenged and restricted at every turn.

A just and equitable multiracial democracy depends on a strong and resourced civic infrastructure centered on local needs. This brief report will detail how current voter registration and civic engagement costs have unreasonably shot up as a direct and intended result of these laws and why funders dedicated to strengthening democratic institutions and systems must boldly expand their investments to meet the moment. We will also look at how new right wing–crafted regulations in states like Florida are impacting democracy groups on the ground in both blue and red states.

This is part of a series of briefs and conversations NCRP is leading about philanthropy’s role in fully resourcing vital civic engagement work led by 501(c)(3) organizations in 2024 and beyond.

3 Major Obstacles to Building a Multiracial Democracy

1. Civic Underfunding, Especially During Non-Presidential Election Years

Though presidential election cycles get most of the public and media attention, grassroots leaders and other experts properly note that civic participation is a habit that is built and expanded in local elections and other off-cycle years. As a result, funders should be looking to generally support and strengthen democratic institutions with multi-year grantmaking strategies that help build local power through a series of elections in every cycle and not just in presidential election years.

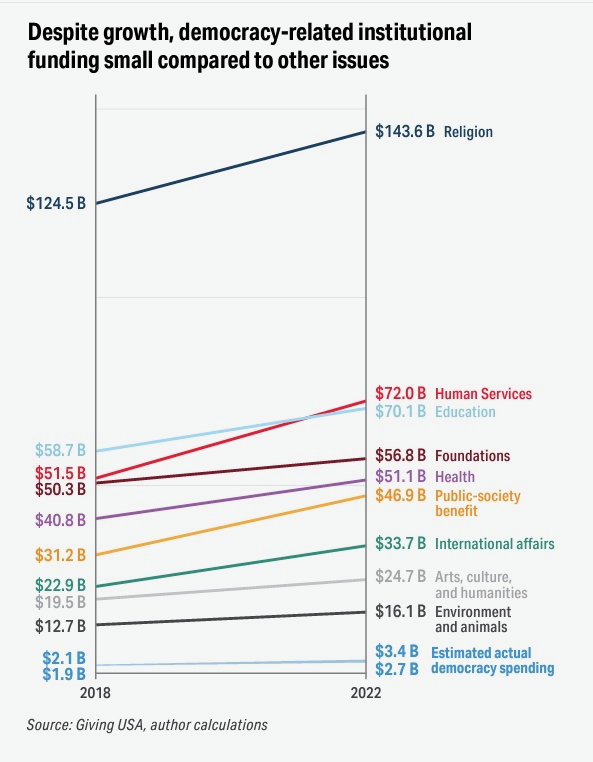

Yet, according to a Democracy Fund analysis using data from Candid, Giving USA and other grantmaker data, philanthropic investments in the democracy field continue to trail those in other issue areas. While estimated funding increased from between $1.9 to $2.1 billion in 2018 to between $2.7 to $3.4 billion in 2022, recent totals still only account for less than 1% – 0.7% – of overall philanthropic spending in 2022.2

Democracy funding spent on voter education and engagement is even smaller. From 2017–2018, between $4.9 to $5.4 million (in 2023 numbers) was spent for initiatives designed to enlist and engage new voters. By 2021, that number had risen only slightly to between $6.5 to $7.7 million, despite the unprecedented threats to our democracy within those 4 years. Among the 12 most prominent democracy funders, only 6% of their democracy funding was for voter education and engagement.3 In other words, only a facet of overall funding was intended to expand the electorate and safeguard the participation of communities and people of color in our democratic process.

2. Rise in Inflation Means Grant Dollars Have to Stretch Further

The struggle for funding is made more complicated by the rising costs of expenses due to inflation. Since 2021, average national rates of inflation have hovered around 4% and reached a high of 8% in 2022. Inflation rates vary by state, and many of the states with new restrictions on voter engagement have above-average inflation too – for example Florida, Texas, South Dakota and North Carolina.

Civic engagement organizations have seen expenses rise with inflation, forcing them to do more with less. For typical 3PVROs like FLIC and Florida Rising, baseline expenses include everything from overhead costs to holding seasonal voter registration events to training residents to knock on doors and engaging potential registrants/voters in different environments.

As a result, $1 that was given to civic engagement organizations 5 years ago only covers $.81 of those expenses in 2024. The lack of investment not only destabilizes our democracy, but also shifts more of the costs of voting to individual voters. Data published as recently as April 2024 by All Voting Is Local estimates a first-time voter in the U.S. will have to spend approximately $105.53 to vote in the upcoming elections.

3. Increased Voter Suppression Legislation and Regulation in GOP-led states

Grassroots multi-issue civic education and participation organizations have sought for years to inspire traditionally hard-to-reach communities with creative organizing tactics. They employ strategies that are responsive to local conditions and moments and engage with community residents in a manner that invites them to become active participants that hold elected officials and other power structures accountable to the people they represent.

These organizations are skilled in working around systemic barriers to engagement that limit participation in civic processes, including limited access to public transportation, childcare and multilingual resources. One of their core goals is to ensure that their community knows the role they play in our democracy: American democracy is for them and therefore must be made “by them.”

The effectiveness of these groups makes them the target of right-wing attacks on voting access and participation. For example, there are now attempts to curtail and even outlaw organizers that work with legal permanent residents and undocumented residents to mobilize voting-age and eligible friends and family to go the polls. These attempts have increased the financial and programmatic need for legal resources – both to fight such efforts and hold ground on or defend what was once a standard or common practice in the field. This has the dual impact of draining the resources of key democracy supporting groups while also contributing to lower turnout from marginalized communities.

Legislation that adds additional burdens to democracy’s infrastructure and institutions can be classified in 2 ways. One set, in the name of so-called (and largely manufactured) “security concerns,” adds or increases administrative costs for organizations spearheading voter education and registration efforts:

- Training and certification requirements for organizers – Voter engagement requires dozens – not hundreds – of paid canvassers and increasingly burdensome state requirements mean organizations must pay canvassers for their time during state-required trainings as well as provide specialized in-house training before they are ready for the field. These burdens create a compliance effort that could require the full-time attention of 1 or more management-level staffer as well as requiring up to a quarter of canvassing staff’s time.All of this staff time – layered on top of what is required to reach voters – could potentially add up to a sum of several thousand dollars per cycle in additional costs.

- Requiring organizers to collect copies of voter identification documents – In addition to increasing the time an organizer needs to register each voter, compliance requires dedicated staff time to securely store documents, increasing overall program costs by tens of thousands of dollars each cycle.

- Shortening registration return deadlines – Shortening the window of time within which completed voter registration forms need to be returned to the state increases the labor costs needed to comply, potentially by tens of thousands of dollars each cycle. For example, a return window of 10 days to return registration forms to county or state officials requires twice as many field operators as a 20-day return window requires. While the expectation for tight turnaround of voter registration forms has been long held, new state-level regulations create extreme consequences for all human delays or errors, which push the form submission beyond the 10-day window. Fines for any form return delays are assessed per form per day and can compound up to $250,000 per organization per calendar year.4 As a result of these new requirements, just a single staff illness, accident or misstep can lead to outsized consequences for workers and debilitating fines that harm under resourced community organizations.

The second set of obstacles and hurdles focuses on limiting how individual impacted community members can be a part of civic solutions. It looks to directly limit or restrict those who organizations can hire to do the work of registering new voters:

- Restricting compensation for organizers – One tactic laws aimed at limiting civic engagement are using is restricting the wage a field operation can pay organizers via preemption at the state level. While such efforts might superficially look to address rising labor costs, the impact of limiting what organizations can pay people in an environment of inflation and increased costs of living creates more problems than it solves. In fact, efforts like these shift the cost of recruiting good organizers to field managers and other staff who are already working at capacity. In practical terms, creating an artificial wage ceiling shrinks both the applicant pool for organizers or canvassers while adding more time to the labor required of hiring managers working to fill those positions.

- Banning returning citizens or noncitizens from certain kinds of civic engagement organizing. The ground success of many organizations can be linked to their ability to recruit trusted residents to drive local civic engagement efforts and convince their neighbors to go to the polls. In some cases, individuals who do not have the right to vote view this as a way to engage in our democratic process – supporting those with the right to vote to take advantage of that right and get to the polls, even if they can’t. This includes formerly incarcerated individuals, youths under 18 and residents who don’t have full citizenship status. Several states have enacted laws that limit and control who can register voters – such as only allowing U.S. citizens to collect signatures or work on issue-based education campaigns and requiring that only U.S. citizens volunteer at the polls on Election Day. Reaching voters in some communities would be nearly impossible if their undocumented or formerly incarcerated family and support network could not help them understand the importance of voting and registering to vote. At best, it would require organizers to spend 2 to 3 times as much of their time in these communities to establish the same reach and encourage the same volume of potential voters to participate.

- Increased fines and criminal penalties for individuals, not just organizations, doing the work – Law modeled after Florida’s S.B.7050 are looking to raise or impose new penalties for individuals doing traditional civic engagement work. Alabama’s S.B.1 would slap a Class B felony onto any volunteer or worker who provides a stamp or sticker while assisting voters during election. It would also make it a felony to “‘receive a payment or a gift’ from someone providing routine absentee application assistance.” That would put such actions in the same category of as other Class B felonies like first-degree manslaughter and second-degree rape.5

Keep in mind that these regulations exist in contrast to state level policies in other states which encourage civic participation, including same day registration and the ability to vote by mail.

The Impact of Restrictions on Groups & for Voters

The cumulative impact of these new and increasing administrative burdens on community-led civic engagement work is profound. In states like Florida – where inflation has remained higher than in other states – FLIC estimates that program costs for voter engagement have increased by 50% overall. For example, the cost per completed voter registration “card” went from about $30 in 2020 to about $45 in 2024.

“The cost to run a voter registration operation has increased substantially,” Moné Holder, Senior Director of Advocacy & Programs at Florida Rising, said. “Florida Rising is able to bring costs down a little bit because we are statewide and operate in multiple counties. But smaller organizations incur a bigger overhead.” 6

Legislation that restricts 3PVRO has also had a chilling effect on community engagement and civic engagement work, resulting in the rollback of previously hard-fought gains in registration and participation, especially among communities of color. In a lawsuit challenging Florida’s S.B.7050, University of Florida political science professor Daniel Smith noted how there had already been a drop in voter registrations in 2023 compared to 2019. Smith, a nationally recognized expert on voting rights laws and behavior, has noted in the past that Floridians of color are 5 times more likely than white voters to register with third-party groups. Since 2013, Smith’s research has documented that more than 2 million Floridians have been registered or re-registered to vote with the help of a 3PVRO. 7

These bill and laws are not just passing in Republican-controlled states. A list of state legislation that adds administrative obstacles and hurdles includes blue states like California,8 Colorado,9 Delaware,10 Maryland,11 and Oregon.12 Challenging and defending this legislation an increasing part of election strategy for both political parties, thus the costs of litigation must also be factored into the expenses of civic engagement organizations and coalitions.

Philanthropy’s Obligation is Clear

Regardless of local partisan benefits, we are living in a world where authoritarianism and restrictions on voter education, registration and mobilization are on the rise. A recent study by McKinney Grey Analytics shows that people of color are being systematically sidelined by “seemingly inclusive, data-driven digital systems” of voter engagement. According to the Public News Service, their analysis of U.S. Census data indicated that “among voting-age Americans, nearly 25 million Black and brown eligible voters are missing from commonly used registration databases.”

FLIC Deputy Director Renata Bozzetto said that now more than ever, we need culturally sensitive engagement campaigns that will help to bridge the huge gap has been created by new voter disenfranchisement and restrictive laws.

“Restrictive laws that make civic engagement incredibly difficult pose a substantial barrier to democracy,” Bozzetto said. “It’s morally wrong to have people out of the voter roster simply because they are afraid of completing a voter registration card alone. It is really problematic to keep people waiting for a vote-by-mail ballot that will never come because we now have a law that has canceled their vote-by-mail request without their knowledge. It isn’t democratic that people choose not to vote because they are intimidated by anti-immigrant rhetoric.”13

Philanthropy has an opportunity to address these obstacles and eliminate the increasing administrative strain on civic participation throughout the year and across all election cycles. Grantmakers and wealthy donors should listen to their grantees and trust the expertise of grassroots leaders about what it will cost to run programs effectively. They should ultimately provide larger and more flexible grants that enable grantees to build and run effective programs.

Having these multiyear commitments in place helps ensure that these frontline grassroots-powered organizations can build sustainable infrastructure that can become more strategic through applied innovation and learning. Funding that leads to immediate and long-term stability helps protect democracy in this current moment of crisis and for the long haul.

There’s no one better equipped for transformational investment than a community-based issues organizing group with established relationships in and knowledge of its own communities. Groups like these are uniquely qualified to reach and mobilize voters who are underrepresented in the electorate. They are equally – if not more – important to the civic engagement ecosystem as groups that are only focused on voter registration.

Mónica Hernández, co-director of the Southeast Immigrant Rights Network (SEIRN), said that a thriving and powerful grassroots movement depends on funder infrastructure investments that support organizations through the current crisis without taking away from the resources that are needed to build the long-term work that is needed to make organizations sustainable.

“What does that look like? It means supporting spaces where our movement and our community leaders can gather to learn and strategize together. Where they can build relationships and trust, uproot internalized biases and divisions within our movement, and address the trauma that is caused by systemic oppression,” Hernández said. “But for directly impacted people to engage in our movement, we also need to address the barriers to participation. That means investing in childcare, providing transportation stipends to replace lost wages, and the kind of language justice that goes beyond just simple interpretation to creating an environment where people can use the language that they are most comfortable with. Where the onus on understanding isn’t only on non-English speakers.”

“It also means investing in healing work, in the inner work and relational work to prevent the burnout and address the relentlessly traumatizing and re traumatizing nature of the work,” Hernández continued. “And this applies not only to paid staff, but it applies to community leaders and community members. It applies to the whole ecosystem.”14

Stable, responsive investment builds a solid foundation for civically focused community-based organizations while also strengthening democracy by helping to create the kind of future we all want to see – for our country and ourselves. Now is not the time to be sheepish. We must fund early, often and in and outside of the election year. This is the way we combat voter suppression once and for all and build a truly multiracial democracy.

For Advancement Project Executive Director Judith Browne Dianis, the urgency to act boldly is the only response available against those who will not rest until they accomplish their own goals.

“There are no off years for vote suppressors,” Browne Dianis said. “The bottom line is that they want power, and they see this shifting demographic of America as a threat to their power. They don’t take off-years, right? There are no off years. So what that means is for funders is that we need to be funded for transformation not transaction.”15

As so many others have said, we must dutifully fund this work like our democracy depends on it.

Because it does.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

ENDNOTES

1 ALABAMA STATE CONFERENCE OF THE NAACP ET AL. V. MARSHALL ET AL. ACLU Alabama. (2024. April) https://www.aclualabama.org/en/cases/alabama-state-conference-of-the-naacp-et-al-v-marshall-et-al. Last accessed Sept. 19, 2024.

2 Though democracy funding has grown more quickly than all philanthropy since 2018 (61% versus 17%) and its share has increased over time, other discrete issue areas still saw far greater investment in 2022. Field in Focus the State of Pro-Democracy Institutional Philanthropy. pg. 14. (2023, October). https://democracyfund.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Field-in-Focus-3.pdf. Democracy Fund. Last accessed Sept. 19, 2024.

3 Ibid

4 In Florida, S.B.7050 would impose fines of up to $250,000 per year per organization for infractions like returning a registration 11 days after a voter completed it, not the legally mandated 10. Lopez, A., & Mendelson, A. (2024, May 16). Voter registration drives cut back after Republican state laws: NPR. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2024/05/16/1251289736/voter-registration-drive-state-restrictions. Last accessed September 19, 2024.

5 ALABAMA STATE CONFERENCE OF THE NAACP ET AL. V. MARSHALL ET AL. ACLU Alabama. (2024, April) https://www.aclualabama.org/en/cases/alabama-state-conference-of-the-naacp-et-al-v-marshall-et-al. Last accessed Sept. 19, 2024

6 2024 & Beyond: Critical Funding Needs to Create a Multiracial Democracy (Funder Briefing). NCRP. (2024, May 29)

7 Ibid

8 California requires that 3PVROs requesting 50 or more blank forms submit documentation to the secretary of state. Documentation is also required for individuals compensated to help register voters. Completed applications must be returned to the county election official within 3 days of receipt or by close of registration, whichever is earlier. Movement Advancement Project | Diverging Democracy: The Battle Over Key State Election Laws Since 2020. (2024, June). Movement Advancement Project. https://www.mapresearch.org/2024-election-trends-report. Last accessed September 19, 2024.

9 Colorado requires that registration drive organizers complete training and subsequent testing through the secretary of state. Applications must be returned no later than 15 days after the application is signed or by the registration deadline, whichever is earliest. Movement Advancement Project | Diverging Democracy: The Battle Over Key State Election Laws Since 2020. (2024, June). Movement Advancement Project. https://www.mapresearch.org/2024-election-trends-report. Last accessed September 19, 2024

10 Delaware requires training to distribute state-specific registration forms. Groups are also encouraged to register with the state election commissioner. Applications are generally required to be submitted within 5 days of completion. Movement Advancement Project | Diverging Democracy: The Battle Over Key State Election Laws Since 2020. (2024, June). Movement Advancement Project. https://www.mapresearch.org/2024-election-trends-report. Last accessed September 19, 2024

11 Maryland requires training for persons who wish to obtain more than 25 applications per day. Completed applications must be returned within 5 days of receipt or by the registration deadline, whichever is earliest. Movement Advancement Project | Diverging Democracy: The Battle Over Key State Election Laws Since 2020. (2024, June). Movement Advancement Project. https://www.mapresearch.org/2024-election-trends-report. Last accessed September 19, 2024

12 Oregon requires that organizations requesting more than 5,000 voter registration applications develop a distribution plan and submit the plan to the secretary of state. Completed applications must be returned within 5 days of receipt. Movement Advancement Project | Diverging Democracy: The Battle Over Key State Election Laws Since 2020. (2024, June). Movement Advancement Project. https://www.mapresearch.org/2024-election-trends-report. Last accessed September 19, 2024

13 “2024 & Beyond: Critical Funding Needs to Create a Multiracial Democracy (Funder Briefing).” NCRP. (2024, May 29)

14 Webinar – Building a Multi-Racial Democracy by Investing in Immigrant and Refugee Movements Before, During, and After Elections. Grantmakers Concerned with Immigrants and Refugees (GCIR). (2024, July 25).

15 Ibid

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

ABOUT THE AUTHORS.

Timi Gerson

Vice President and Chief Strategy Officer

Jackelin Trevino

Membership Movement Manager

Stephanie Peng

Movement Research Manager

Suhasini Yeeda

Editorial Manageradditional editing provided Elbert Garcia and Ryan Schlegel