“People tell stories in order to live.” – Joan Didion

After nearly 4 decades tracking the rise of authoritarianism in American politics, I’ve reached an inescapable conclusion: The battle for democracy is not won or lost not solely at the ballot box, but also in the stories we tell. The authoritarian right understood this decades ago. Those of us committed to democracy are still catching up.

What I’ve observed is both alarming and instructive. The authoritarian transformation of our politics didn’t happen overnight or by accident. It succeeded because its architects mastered the art of strategic storytelling long before they gained electoral power.

Consider how meticulously crafted their narrative strategies have been. Make America Great Again isn’t merely a catchy slogan; it’s a powerful story of national decline. It taps into nostalgia for a mythologized past that conveniently existed before civil rights, feminism, and multiculturalism challenged traditional hierarchies.

But perhaps their most brilliant move was redirecting legitimate economic pain toward cultural scapegoats. As globalization and deindustrialization hollowed out communities across America, authoritarian forces offered a compellingly simple explanation: Your suffering isn’t because of corporate power or policy failures, but because “those people,” groups like immigrants, so-called “coastal elites,” and the “woke mob,” are taking what’s rightfully yours.

Through these moves, the authoritarians framed their movement not around policy, but around identity, grievance, and belonging, turning political participation into a form of cultural solidarity rather than an engagement with governance. The effectiveness of this approach stems partly from narrative discipline. While progressive movements debated nuance and complexity, the right hammered simple, emotionally resonant messages across multiple channels. Through relentless repetition, they naturalized an “us versus them” framework that proved remarkably resistant to contrary evidence.

They also mastered what I call “strategic provocation and victimhood inversion” – deliberately provoking outrage then framing the response as persecution. When called out for attacking vulnerable communities, they cry “cancel culture” and position themselves as martyrs for free speech, transforming accountability into oppression.

What’s crucial to understand is that these weren’t reactive tactics. These moves represented sophisticated strategic foresight. The authoritarian right anticipated how globalization, automation, and financial capitalism would reshape communities and create economic anxiety and cultural displacement. They developed explanatory frameworks and villain narratives ready to activate when these crises emerged.

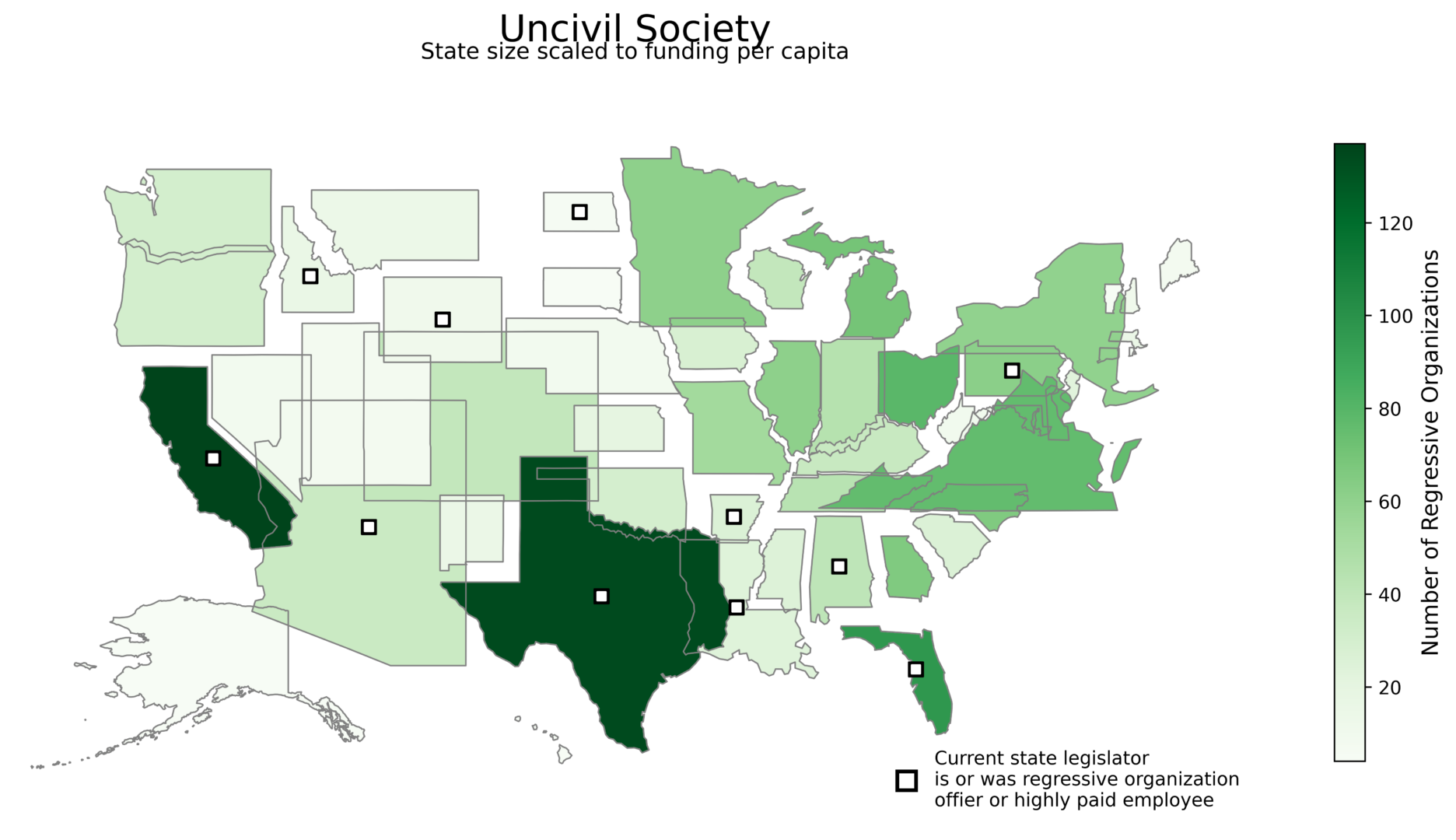

They built alternative media infrastructures, like right-wing talk radio, before the digital transformation made such efforts profitable. For instance, evangelical authoritarians created the 700 Club, which was the communications organ and chief fundraising vehicle of the Christian Coalition, a national group that provided training, strategic support, and public opinion research to local evangelical authoritarians so that they could punch above their weight class. Similar media outlets like the Trinity Broadcasting Network served both as soft entry points into the evangelical movement and as the means by which to amass resources in order to expand the networks, with occasional specific fundraising appeals to build transmitters to “lift the darkness” over countries like Haiti where they also supported missions.

They also crafted epistemic frameworks like “fake news” and “liberal bias” that would allow their audiences to reject unfavorable information once their narrative foothold was established.

In essence, they didn’t just respond to economic transformations. They prepared the narrative ground to exploit them, investing in storytelling infrastructure with long-term rather than immediate payoffs.

Building Collective Community Courage

So how do we counter these narratives without adopting their manipulative approaches? The answer lies in building better stories and narratives that energize democracy rather than authoritarianism.

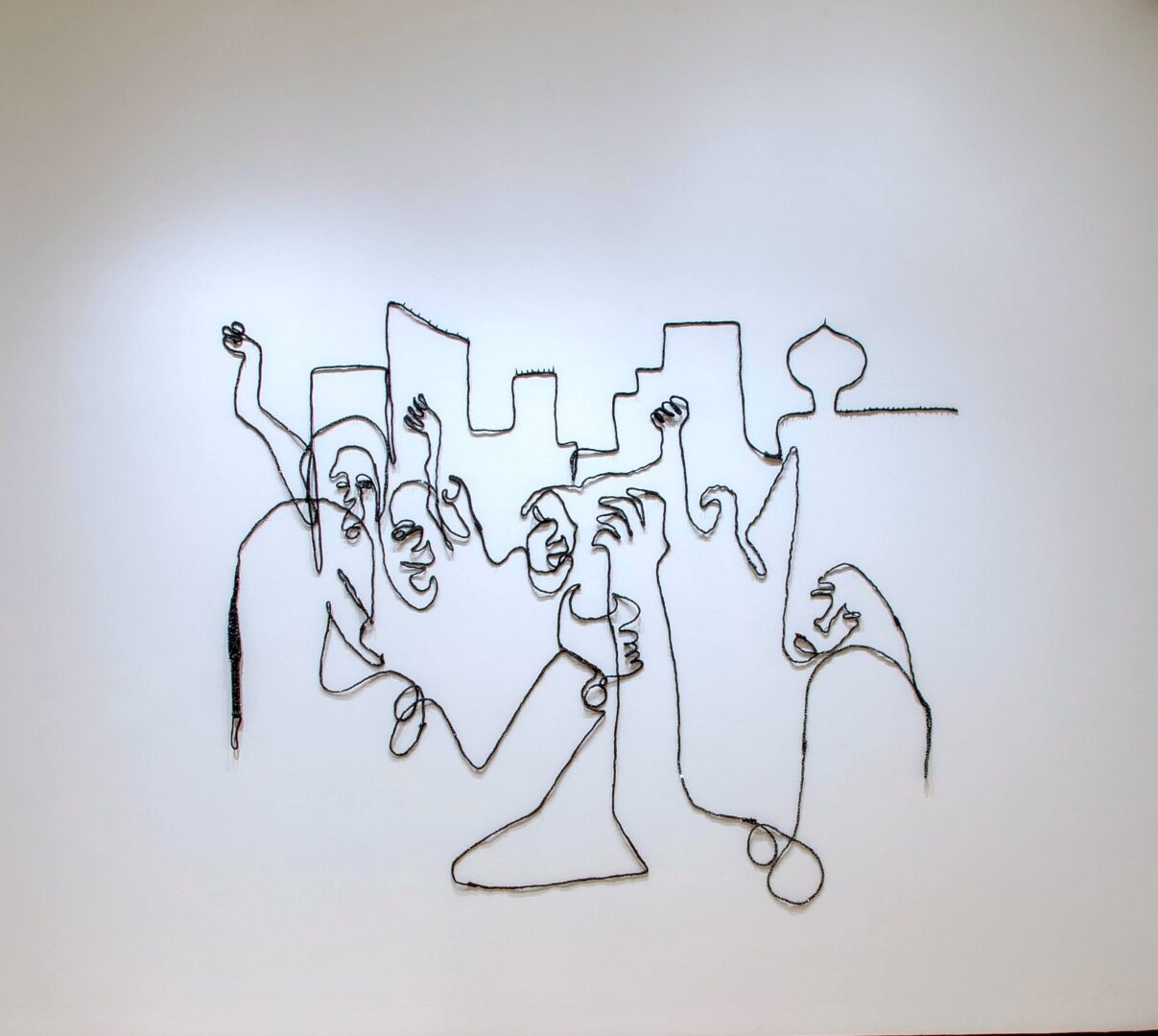

We can draw inspiration from movements that have successfully challenged authoritarian power through strategic storytelling. During the Civil Rights Movement, the Highlander Folk School created story circles where sharecroppers and domestic workers shared experiences of both oppression and resistance. These weren’t therapy sessions but strategic spaces that surfaced forgotten tactics and built collective community courage.

Chile’s 1988 campaign against former President Pinochet shows how joy can defeat fear. Rather than focusing solely on the dictator’s brutality, they created forward-looking messaging celebrating democracy’s possibilities. Their rainbow symbol and testimonials from ordinary Chileans portrayed democracy as abundance rather than scarcity.

The human rights organization known as Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo in Argentina demonstrate distributed storytelling’s power. During the Dirty War, each mother became a bearer of her disappeared child’s story, their white headscarves symbols that carried their narrative even when words became dangerous. This approach meant the government couldn’t silence their movement by targeting any single leader.

What unites these examples is that they didn’t merely oppose authoritarianism, they embodied democratic alternatives through the very way they told stories.

Drawing from these lessons, our narrative strategy must balance complexity without confusion. Authoritarian narratives offer simple solutions to complex problems. Our challenge is developing clear frameworks that hold multiple perspectives while still driving toward action.

We must center agency, not just victimhood. Stories documenting suffering without highlighting resistance create a sense of powerlessness. Effective democratic narratives balance acknowledging harm with showcasing the power of collective action, demonstrating that change is possible.

We need tactical narrative diversity. No single story type will reach all communities. We need personal testimonials building emotional connection, analytical stories explaining systemic patterns, cultural expressions transcending rational barriers, and yes, humor that deflates authoritarian pretension.

Investing in Counter-Authoritarian Storytelling

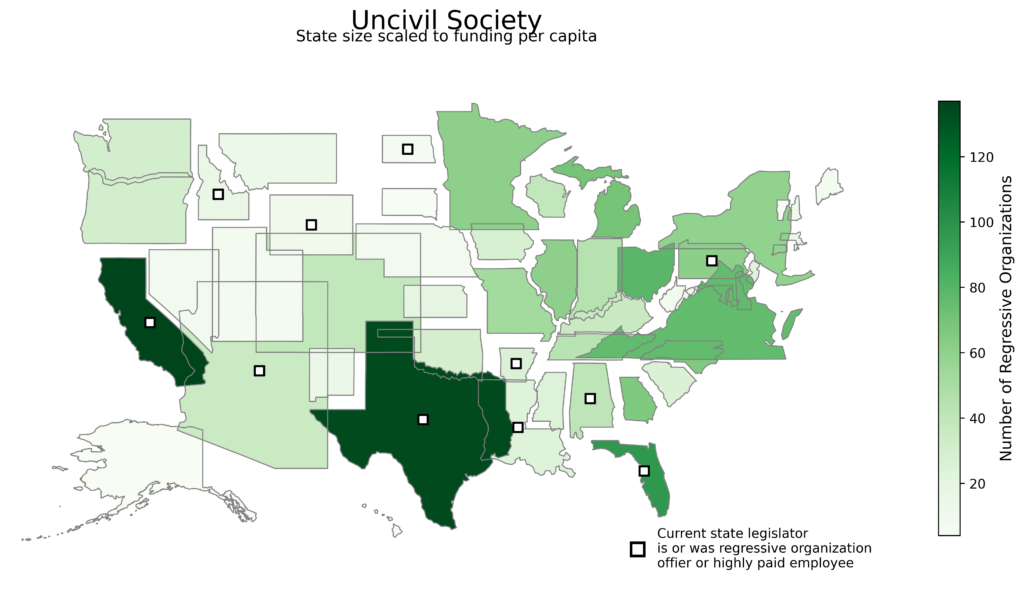

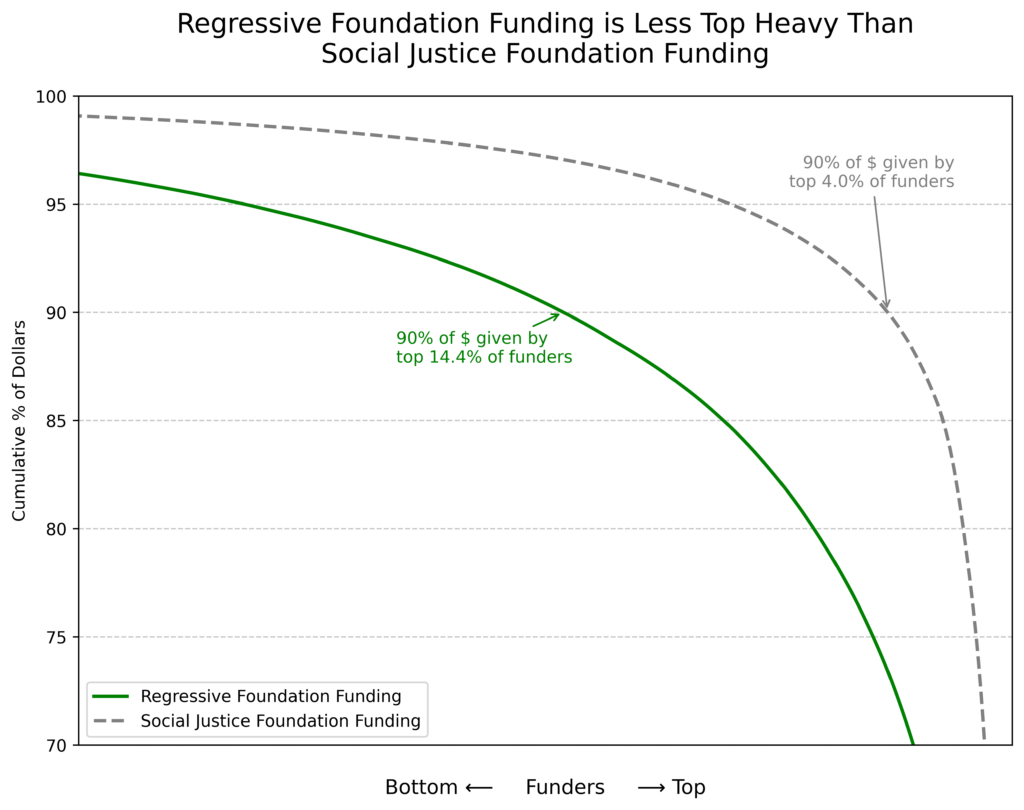

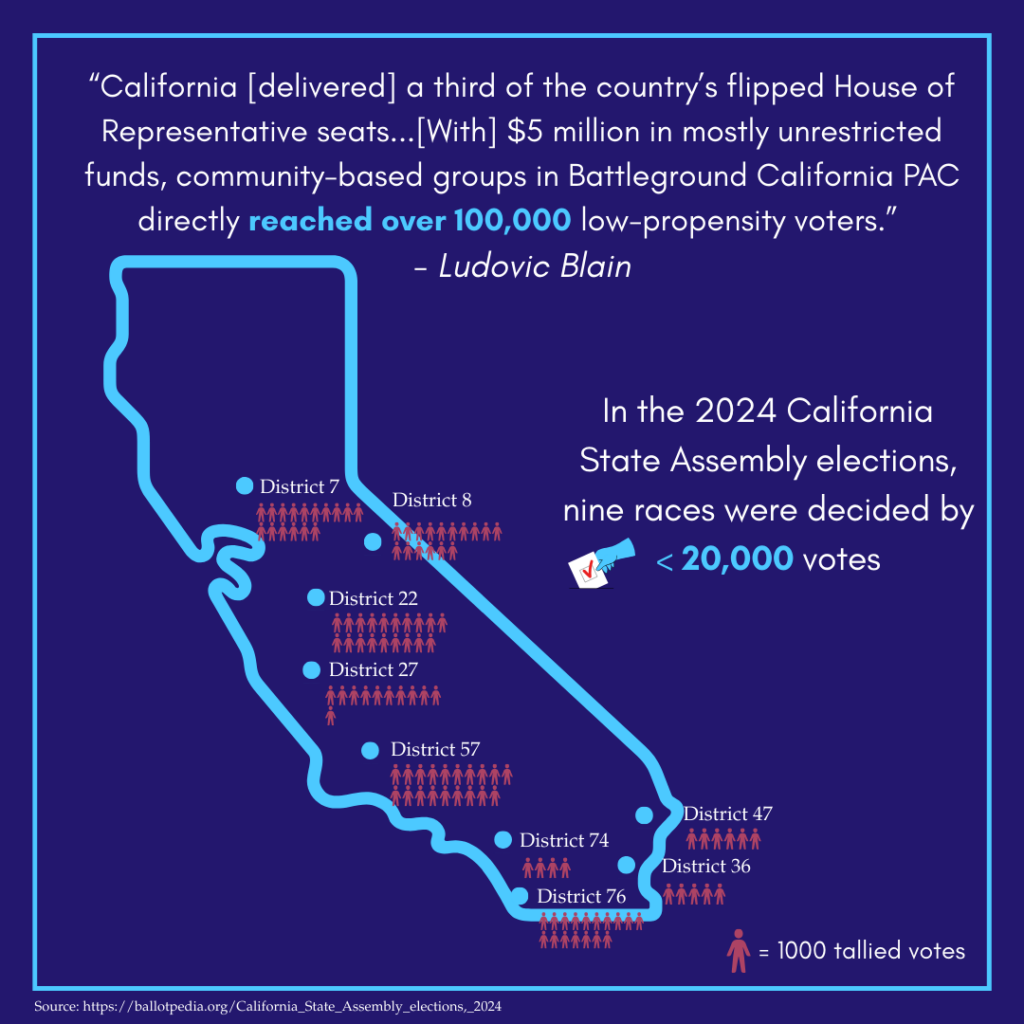

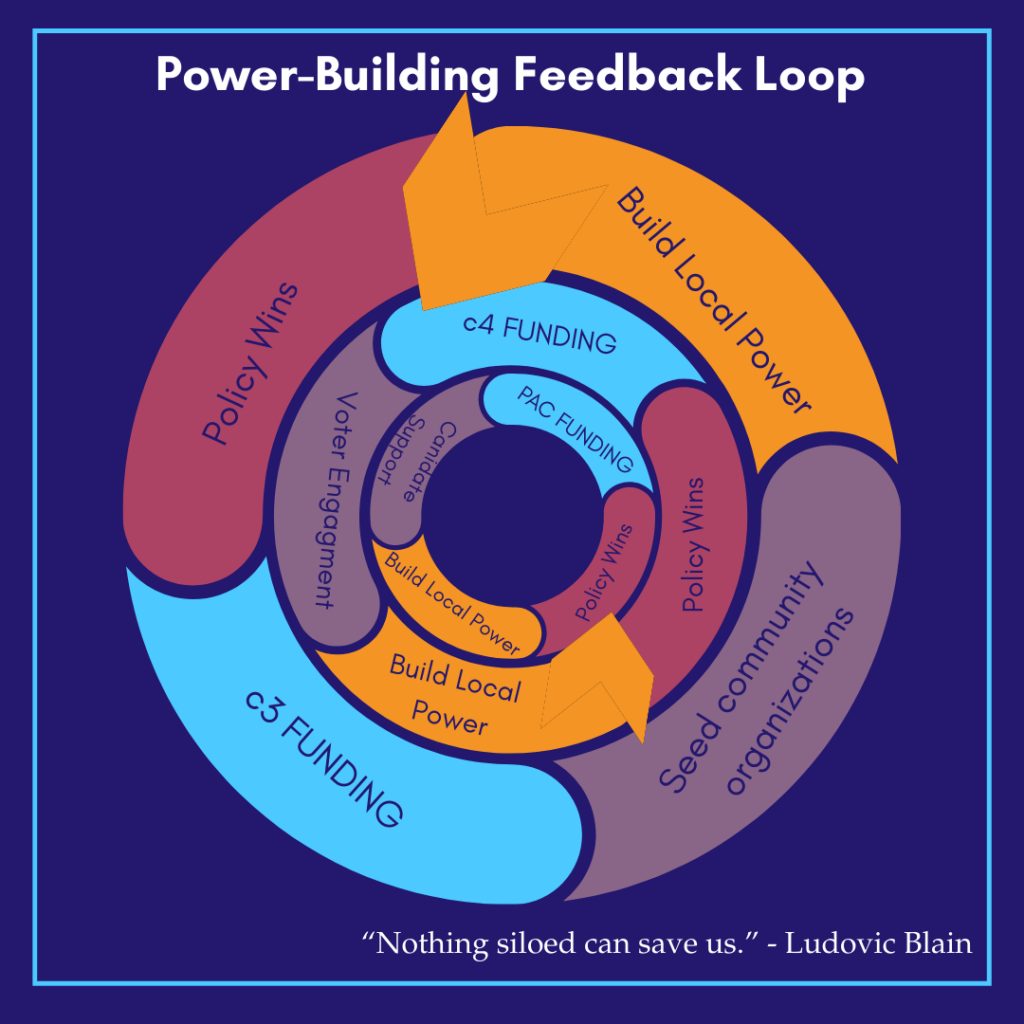

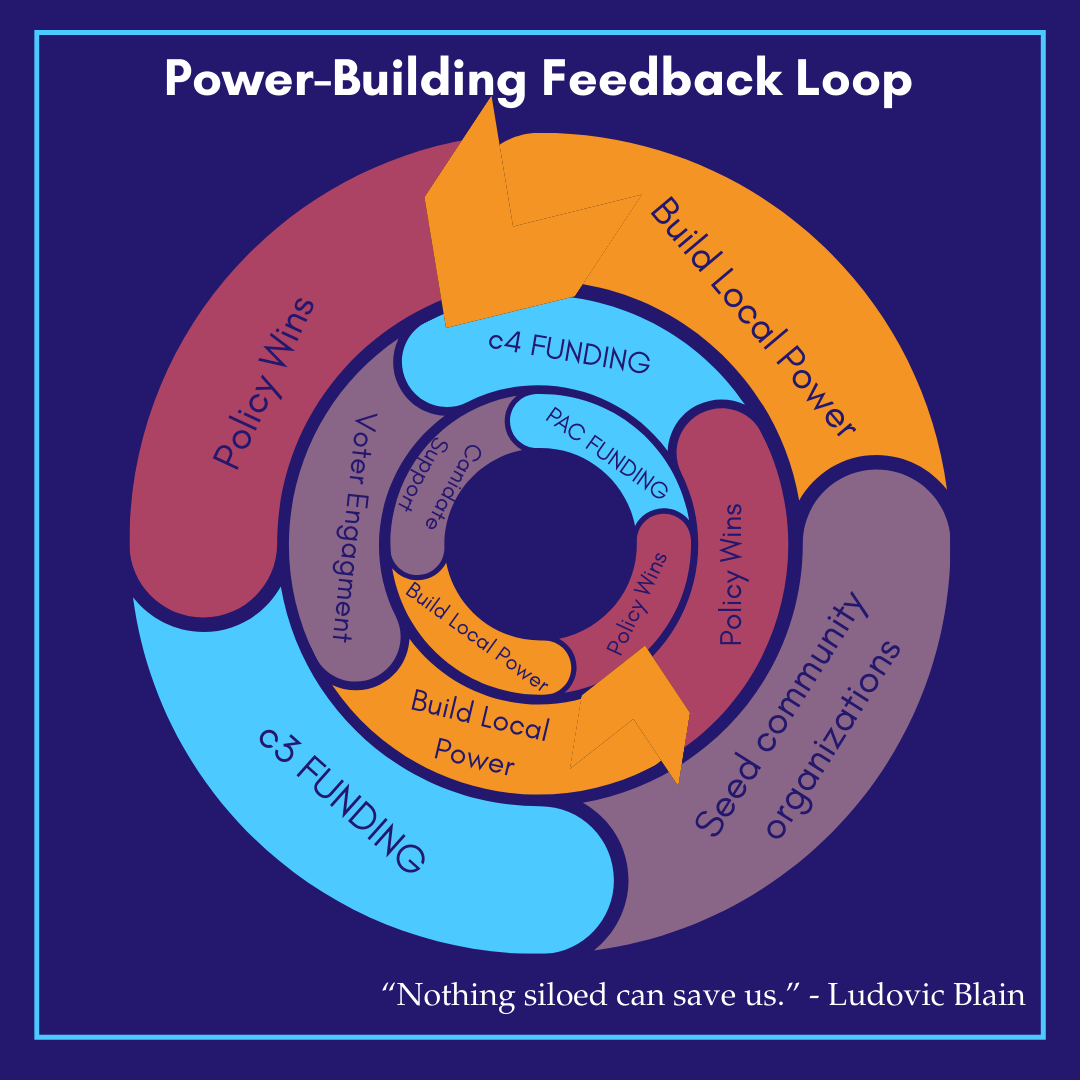

This work requires serious investment. Funders must support narrative infrastructure beyond election cycles, including community media controlled by movements rather than corporations, physical spaces for thousands of story circles, and documentation systems preserving movement histories for future inspiration.

Organizers must treat storytelling as a core strategy. We often share ideas rather than stories and present those ideas as sales pitches for participation in issue campaigns and candidates. These tactics are still valuable, but we must adapt to the challenge before us by centering storytelling. We need to create spaces where people can connect personal experiences to systemic analysis, build storytelling capacity across diverse communities, and craft bridge narratives that connect divided groups through shared values.

Most importantly, we must recognize that counter-authoritarian storytelling isn’t just about better messaging, it’s about building the democratic world we want through the very practice of telling stories together.

When people gather to share experiences of struggle and resistance, they form what narrative expert Liz Manne calls “constellations,” meaning narratives that connect diverse stories to make the whole greater than the sum of its parts. Narratives of this sort are a critical component of the infrastructure of democratic power.

The authoritarians have treated narrative as warfare and invested accordingly. If we hope to counter them effectively, we must take storytelling just as seriously – not as manipulation, but as democracy’s fundamental practice.

The stories we tell in the coming years will determine whether authoritarianism continues to rise or whether we can yet build a democracy worthy of the name. This is a battle we cannot afford to lose.

Scot Nakagawa is a political strategist and organizer with over 4 decades of experience exploring questions of structural racism, white supremacy, and social justice. He is the co-founder and director of the 22nd Century Initiative, a national strategy and action hub building power at the intersection of opposition to authoritarianism and expanding democratic governance in the United States.