Chavies, Kentucky, isn’t on the way to anywhere. Located in Coal Country 200 miles as the crow flies from three of the fastest-growing economies in the country, the town of 500 is three hours from the nearest commercial airport, by winding mountain roads, at the heart of one of the largest concentrations of persistent poverty in the country. At the other extreme of the American South, the Lowcountry of South Carolina is exploding with economic growth that threatens to destabilize centuries-old communities.

Chavies, Kentucky, isn’t on the way to anywhere. Located in Coal Country 200 miles as the crow flies from three of the fastest-growing economies in the country, the town of 500 is three hours from the nearest commercial airport, by winding mountain roads, at the heart of one of the largest concentrations of persistent poverty in the country. At the other extreme of the American South, the Lowcountry of South Carolina is exploding with economic growth that threatens to destabilize centuries-old communities.

As different as they seem, the Lowcountry and Coal Country are both at the vanguard of a national, and even global, economic transition that will set a course for communities like them everywhere.

The Southern economy was built around the backbone of the fertile agricultural Black Belt – and on the backs of the enslaved people who worked there. After white colonizers forced Native people off the land, they set about enriching themselves off the fertile soil and slave labor. On the margins of the Black Belt are lands that the rich and powerful of yesterday’s South did not want. Appalachian hills and hollers were too isolated, their resources too hard to access. Coastal marshes teemed with bugs and sweltered in the summer sun. But the landscape of Eastern Kentucky was a draw for pioneers and colonists seeking solitude and autonomy from mainstream urban life in the Colonies.

The story of Appalachian people is complicated – though early colonists were not wealthy slave-owners like their countrymen in the Black Belt, they were complicit in the expulsion of Native people. A century and more later, their descendants drove the coal economy and provided the nation with cheap profitable energy. In the Lowcountry, planters similarly drove Native people from the land. In later years freed slaves, who once made South Carolina rice one of the most profitable crops in the country, settled remote islands, lived in relative peace and independence, and passed down a unique transatlantic culture.

The story of Appalachian people is complicated – though early colonists were not wealthy slave-owners like their countrymen in the Black Belt, they were complicit in the expulsion of Native people. A century and more later, their descendants drove the coal economy and provided the nation with cheap profitable energy. In the Lowcountry, planters similarly drove Native people from the land. In later years freed slaves, who once made South Carolina rice one of the most profitable crops in the country, settled remote islands, lived in relative peace and independence, and passed down a unique transatlantic culture.

These rural communities are no longer as isolated as they once were. Globalization has made them more accessible to more people and more economic development than ever before. In recent years, demand for coal from Eastern Kentucky has declined, as cheaper sources of coal and alternate energy sources become available, and the region’s dependency on coal as an economic driver of wealth has been disrupted. In coastal South Carolina, housing and commercial developments following new roads and bridges built in the 1950s, along with regressive state policy incentives, have attracted a growing manufacturing industry that is threatening Lowcountry communities’ way of life.

The vibrant history and distinctive culture in each region were shaped by their isolation from the rest of the country. And their future will be shaped by the tension between global economic forces and locally-controlled community assets.

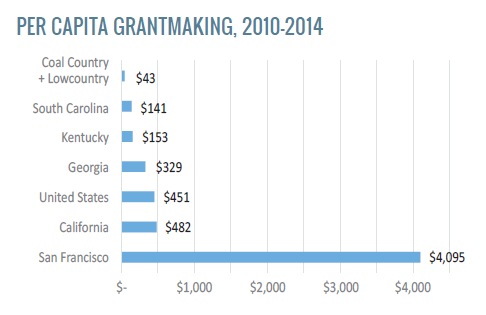

In the first As the South Grows report, we explored opportunities for philanthropic investment in the South for building collective power by supporting existing nonprofit leaders and networks. But building power is only the first step toward achieving a vision of shared prosperity for Southern communities. Systemic change work in the South goes beyond building power; funders must also focus on building wealth in marginalized communities. Community economic development in the South is sometimes not seen as a viable strategy to advance equity and justice. But, especially when community asset building directly addresses the South’s history of extraction, exploitation and systematic exclusion from economic opportunity, it is indeed a long-term systems change strategy.

In the first As the South Grows report, we explored opportunities for philanthropic investment in the South for building collective power by supporting existing nonprofit leaders and networks. But building power is only the first step toward achieving a vision of shared prosperity for Southern communities. Systemic change work in the South goes beyond building power; funders must also focus on building wealth in marginalized communities. Community economic development in the South is sometimes not seen as a viable strategy to advance equity and justice. But, especially when community asset building directly addresses the South’s history of extraction, exploitation and systematic exclusion from economic opportunity, it is indeed a long-term systems change strategy.

Communities across the South already have the assets and capacity to build locally grown and owned wealth and protect other assets such as culture and heritage. Funders and donors may not initially view existing community economic development infrastructure as viable investments. But if philanthropy expands its understanding of community assets and supports innovative, accountable economic development that is truly controlled by communities affected by income, gender and race inequality, those investments can be transformative.

“A national foundation could dump a half a million dollars here right now, and it wouldn’t mean a thing in five years. Or they could help us where we are, with what we have, and really invest in figuring out how we turn this economy around. What does this economic transition look like? I don’t think anyone knows what the answer is, but there are people out there with a lot more resources than I have that could help us answer that question. And I don’t want to go to New York and answer that question; I wish they would come here. If funders are interested in Appalachia, the South, then make a commitment that’s longer than two or three years. Make it 10 years, and don’t throw money at the problems, but participate in the network of folks interested in this place. It’s not pretty or sexy; it’s a slog.”

— Gerry Roll, Executive Director, Foundation for Appalachian Kentucky

How can foundations help communities identify existing assets and capitalize on them? How can foundations support communities to build wealth that is inclusive and protective of local culture? How can Southern economic development be controlled more by the communities it will benefit?

This report will explore the link between community-driven economic development and equity in the South. From the coalfields of Kentucky to coastal South Carolina, organizations and institutions are adjusting to changing economic realities and using innovative strategies to build lasting wealth within their communities.

Voices from Coal Country and the Lowcountry: