|

“My grantees and staff ‘get’ race and class but where’s the gender analysis? What I want to know is: what happened to gender?”

– Senior program officer

“Gender impacts every issue funders address, but program officers are seldom challenged to do innovative grantmaking around gender [like they are race and class].”

– Loren Harris, former program officer for U.S. Youth, Ford Foundation

Two decades of research have found that when young people buy into rigid ideas of masculinity or femininity, they have measurably lower life outcomes in everything from reproductive health and education achievement to economic empowerment and health and wellness.[1]

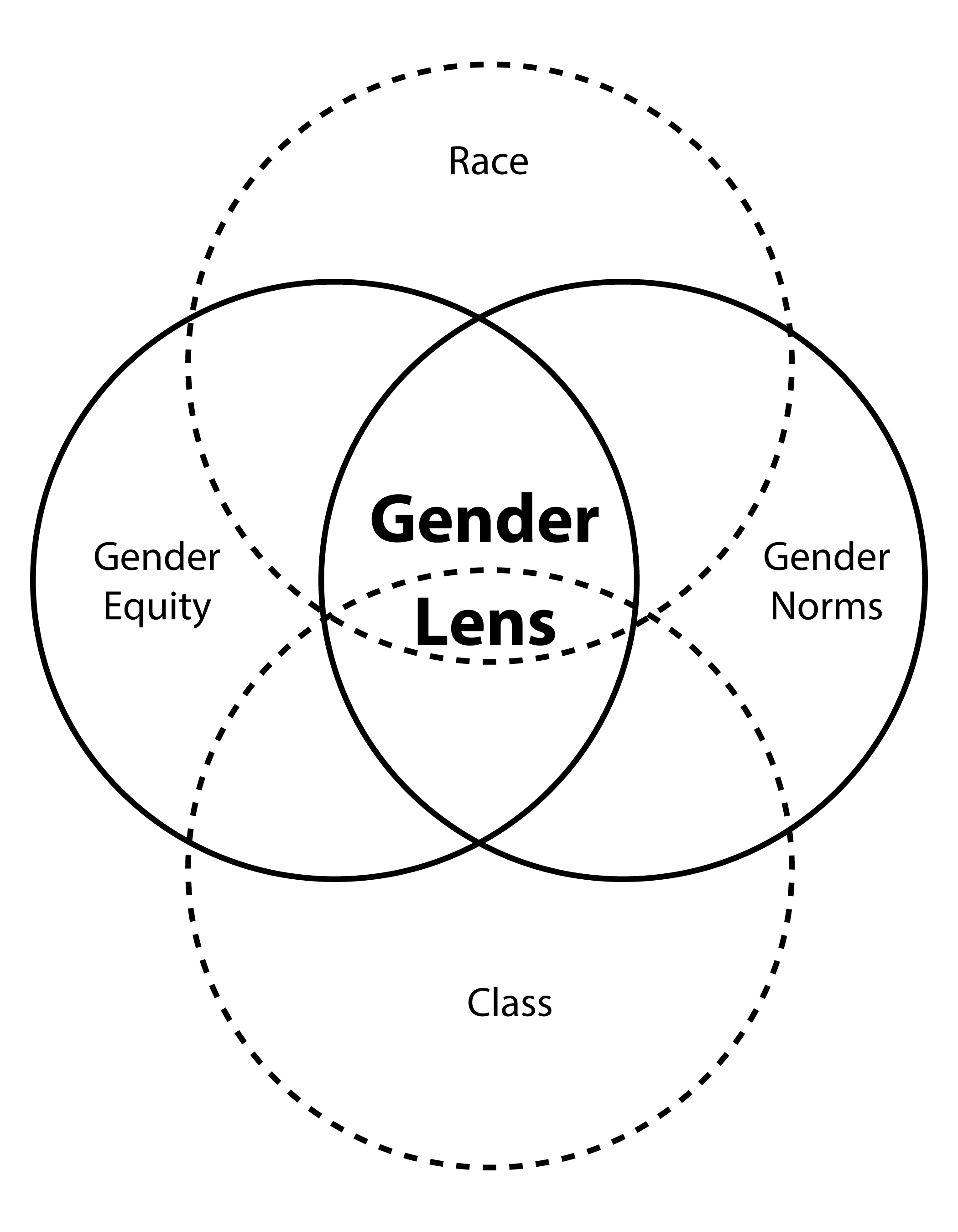

I explored this issue in a recent blog post[2] for NCRP about gender norms – that is, those ideals, scripts and expectations we all begin learning practically from birth for how to “do” boy and girl, woman and man.

Studies show that young women who buy into traditional feminine ideals of beauty, desirability, passivity, motherhood, dependence and conflict avoidance are more likely to equate self-worth with male attention, to worry about their weight and bodies, to have early and unplanned pregnancies, to defer to male sexual prerogatives and tolerate abusive partners and to develop eating disorders or depression.

In education, they’re not only more likely to leave high school early, but also more likely to drop out of STEM courses – or those in science, technology, engineering and math.

STEM literacy is particularly important for girls in low-income communities, because STEM-related professions continue to generate some of the fastest-growing and highest-wage jobs in the emerging knowledge economy.

The STEM field has done a great job of addressing a host of external and interpersonal barriers to girls’ participation, including the lack of role models, parental attitudes, unconscious teacher bias, “chilly” (or sexist) classroom climate and “stereotype threat.” Despite these important efforts, STEM’s well-known “leaky pipeline” begins leaking in earnest in middle school, when even girls who previously got high grades and reported enjoying STEM subjects suddenly begin expressing lack of interest and avoiding STEM electives.

What changes in middle school? We think one answer is feminine norms.

Middle school coincides with what some call the gender intensification period, when interest in traditional feminine norms begins to accelerate and belief in them starts to solidify.

Mastering gender norms is a rite of passage for every adolescent. Young people come under intense social pressure from peers, family members and sometimes adults to master and conform to traditional notions of manhood and womanhood.

Little girls who were confident, outgoing and active can morph into anxious, withdrawn and self-conscious tweens, perpetually worried about their looks and hair and contemplating their first diets.

In terms of STEM, girls entering these years face a double bind: they feel they have to choose between being good at science and math and being seen as feminine and girly. In this contest, STEM loses.

To try to learn more about this, my organization, TrueChild, partnered with the Motorola Solutions Foundation[3] to explore the impact of feminine norms on girls’ STEM interest, participation and achievement.[4] We hosted a series of focus groups with young women. At first, they claimed that they could be both smart and feminine. So they knew the “right” answer – how things were supposed to be.

But they immediately described a classmate with long hair who “no one sees as a pretty girl in that class because she is so smart – she’s like a nerd.” So they knew the reality, too – how things really were.

When we asked specifically if girls could be feminine, smart and popular with boys, they answered, “Yes, but not in junior high!” [laughter] – because as they became more interested in boys, they had to “dumb it down” (a response that is as good as any at showing how a strict philanthropic focus to help girls should not ignore boys).

When we asked them straight out about studies that show that girls stop doing as well in math and science around third grade, they explained:

- “[That’s when] girls start giving up [on math].”

- “It’s when they start noticing the boys [all agree].”

- “[This is when they] start thinking ‘I can’t be pretty.’”

- “Girls focus more on, ‘Oh, he wants me to be pretty.’”

In short, brainy girls who are good at chemistry, can program software or get top grades in trigonometry can be intimidating, or simply unfeminine and unattractive, to boys. And girls know it.

We’ve developed a model mini-curriculum with what expert Geeta Rao Gupta called a strong “gender transformative” focus: it aims to highlight, challenge and ultimately change rigid feminine norms.

Together with our two Motorola Solutions partners – Chicago’s Project Exploration and SUNY’s TechPREP – we’re piloting and refining it and hope to scale it up next year.[5]

And, yes, we hope to develop a similar mini-curriculum that addresses how boys’ attitudes about girls and STEM can hold young women back. This seems to be a big gap in the field.

It’s not that I harbor any illusions about how difficult it can be to change a 12-year-old girl’s mind; I have trouble persuading my 7-year-old daughter to enjoy reading instead of turning on Nickelodeon.

But we can and must begin teaching girls to think critically about feminine norms and their impact on the educational choices they make. We need to at least offer them tools to armor themselves against the intense pressures we know they face.

Gender transformative approaches go beyond STEM. For instance, in partnership with the Heinz Endowments, we’ve been researching and documenting feminine norms’ impacts on health and wellness among young black girls (the report is available on TrueChild’s website),[6] and are now developing a model mini-curriculum.

And EngenderHealth, a TrueChild strategic partner, has been researching, testing and refining an innovative model teen pregnancy program called Gender Matters.[7]

International organizations have shown that gender transformative approaches can work on a host of issues, from reproductive health and partner abuse to fatherhood and infant and maternal care. Now, a growing core of major funders such as the California Endowment, Ford Foundation, MacArthur Foundation, Nike Foundation and Overbrook Foundation – as well as the U.S. Office on Women’s Health – have awarded grants with a strong, specific focus on challenging harmful gender norms.[8]

We believe gender transformative philanthropy is poised to become the leading edge of best practice in U.S. grantmaking.

When it does, its emergence will underscore many of the principles that define NCRP’s approach to responsive grantmaking: flattening issue silos, making funding more evidence-based, addressing at-risk communities and finding low-cost ways to leverage the social return on our philanthropic investment.

For funders seeking to integrate a gender transformative focus into their own strategies, we often suggest a four-step pathway that many of our partners have used:

- Sponsor a paper and/or training to help spark a community conversation on gender, and develop familiarity and comfort with the terms, concepts and key findings.

- Support some simple research (focus groups, interviews) to gain a better feel for the local gender culture.

- Develop a set of simple exercises (or adapt the many existing ones) that grantees can integrate easily into their existing programming without a lot of cost or dislocation.

- We often recommend a TrueChild Gender Audit©, which examines websites, printed materials, current programs and organizational policies. We look for “hooks” where a strong gender focus could easily be incorporated so it becomes part of an organization’s DNA.

For those who aren’t ready for such a deep dive, but still would like to start getting their feet wet, there are plenty of positive steps you can take. We’ve developed a simple introductory “gender 101” for philanthropic officers.[9] And below is a list we hand out at trainings and presentations, “A Dozen Steps Donors Can Take.”[10]

A Dozen Steps Donors Can TakeWithin Your Foundation

With Funder Peers

With Grantee Organizations

|

For more information on TrueChild’s gender approach, be sure to check out our upcoming presentations in Washington, D.C., next month. We’ll be at the JAG Unity Summit on June 6 and the reception of the Council on Foundation’s Philanthropy Exchange on June 9.

Riki Wilchins is the executive director of TrueChild, an action-tank devoted to reconnecting race, class and gender for donors and grantees. The author of three books on gender theory, TIME selected her one of “100 Civic Innovators for the 21st Century.”

Notes

- See http://www.truechild.org/ReadTheResearch.

- Riki Wilchins, “Why Philanthropy Should Address Gender Norms,” Keeping A Close Eye … NCRP’s Blog, March 14, 2014.

- See http://responsibility.motorolasolutions.com/index.php/solutions-for-community/com02-foundation.

- See http://www.truechild.org/STEM and http://www.truechild.org/STEMresearch.

- See http://www.projectexploration.org/ and http://www.stonybrook.edu/techprep/.

- See http://www.truechild.org/Heinz.

- See http://www.engenderhealth.org/our-work/major-projects/gender-matters.php/.

- See http://www.hhs.gov/ash/oah/oah-initiatives/ta/experience_expertise_wilchins.pdf.

- See http://www.truechild.org/funders.

- Developed by Matt Barnes, The Houston Endowments and Rahsaan Harris, Atlantic Philanthropies.